“You’re the cut-off lady!”

I looked at the man who had run up next to me, on the rocky path up to Pen-y-Ghent. A stranger. A smiling bearded man who I didn’t know. I said,

“Huh?”

By now I’m used to people recognising me on races for my socks. But not for being a cut-off lady. Or even much of a lady. I don’t think he explained much more, but said something about me just meeting the cut-offs last year, then he ran off.

About half an hour later, another stranger said, as I passed,

“You’re the cut-off lady!”

This time I properly enquired.

“Huh?”

He explained. His brother (the first stranger) had seen my race report from last year. They knew I had just made the cut-offs, though I wasn’t the last through, and had decided to keep me in their sights as a pacemaker. I said, “wouldn’t you do better to keep me behind you?” I also pointed out that this year I’d done more than three weeks training and was planning on getting to the cut-offs somewhat earlier than 30 seconds after they officially ended.

I had such plans for this year’s race. Such grand plans. But they were not preposterous. I have followed, I think, about 70% of my training plan, supplied by FRB in his coaching capacity as Run Brave coaching. I have gone to weekly Run Brave coaching sessions. My form has improved, and I have had impressive PBs on various sizeable races. On Rombald’s (23 miles) and Heptonstall (15 miles and 3170 feet of climb) I had set off and immediately known that everything was going to be alright. I had felt good, and I keep feeling good. I ran every incline, unless the gradient meant walking was more sensible. I felt strong and powerful and well-trained.

I was really hoping I would wake up on Saturday 27 April and feel the same way. But of course I was worried, for several reasons. I’d flown to Los Angeles and back in five days the week before, which meant ten days of jetlag, as well as about 24 hours cooped up on a plane. FRB and I had gone out to do our last hilly run the weekend before. It was about 25 degrees and blazingly sunny, and we had both felt awful and drained. I had been having the usual menopausal issues, to such an extent that on the Wednesday before the race I drove 260 miles to Stratford-upon-Avon and back to a specialist menopause clinic in the hope of getting fixed. I was prescribed more oestrogen, and so far it seems to be working. But I also went to a Run Brave coaching session after those six hours in a car, and felt sluggish. It was a tempo session, and it should have felt doable: we were doing no more than 8.30 minute miling. But I wanted it to end after the first kilometre. On the other hand, before LA I had gone out to do a session and run 17 hill reps because I felt like it. I had got to the point of really enjoying running up hills, and I remembered being like that the year I did my training properly and did my quickest time on the Three Peaks.

Yin, yang. Yes, no. Success, failure.

Race week proceeded in the usual way: not much running, but constant checking of the Met Office app for Horton, Pen-y-Ghent and Whernside. I don’t know why I bothered checking for Whernside, or any of the peaks: no matter what the weather forecast, the demons who live deep inside the peaks throw up whatever climate they feel like on the day, and never one that you expect. Still, it looked good, because the forecast was for cool temperatures. 8 degrees: perfect. Rain but only one raindrop: fine. I chose to ignore the 30-40 mph gusts of wind. FRB who knows his winds pronounced that we would be pushed up Pen-y-Ghent but would fight the wind to Ribblehead. I followed this by asking him to name all the winds he knew, and I named the ones I had learned from writing about shipping:

Katabatic (a type not a name but beautiful). Mistral. Sirocco. Chinook. The Chocolate Main.

At this he said, “you’re making that up.” But I wasn’t, though I’d got it wrong: it’s the chocolate gale in the West Indies and off the Spanish Main.

By Friday I was not in two minds but several. Still, we followed our usual race prep of going to Billy Bob’s diner near Skipton and eating large amounts of food and – in my case – a very large glass of Dandelion and Burdock, which the diner has at its soda fountain because it’s classy and it’s Yorkshire (it is also classy for having a teens-and-over section because as soon as we arrived we realised that Easter holidays were still ongoing and that most of North Yorkshire’s schoolchildren appeared to be at Billy Bob’s diner).

After that, a wander around Skipton because why not, then we headed to Chapel-le-Dale where we had booked a B&B. The hosts, Martin and Jan, knew of the Three Peaks Race but not that it was on the next day, though their house is half a mile up the road from the Hill Inn checkpoint. The Three Peaks race has filled my thoughts for so long and so vividly I forget that it doesn’t fill other people’s. We went to Ingleton for our usual pre-race dinner of all the chips, and parked in a lay-by for a clear view of Ingleborough, looming in front of us. My nerves were kept in check, but only just.

The next morning was a different story. I was a wreck. Still, we managed to eat a decent breakfast – pancakes for me, cooked breakfast with black pudding for FRB – and we arrived at the race field in good time. Both FRB and I have co-edited the Three Peaks programme this year, and sit on the committee, so we were entitled to a free parking place rather than being parked a ten-minute walk away amongst chickens. There it was again, all of it: the huge white marquee. The Pete Bland Sports van. The Inov-8 van. The stall of Big Bobble Hats. The long row of portaloos. This year there was a toilet improvement, with women’s toilets separated from the men’s, so there could be two queues. I’ve had some insight into race organization from my hands-off presence as programme co-editor (I didn’t go to any meetings), and the effort is huge and I have a new respect for it. Many organizers had been there camping since Wednesday, and they are all volunteers.

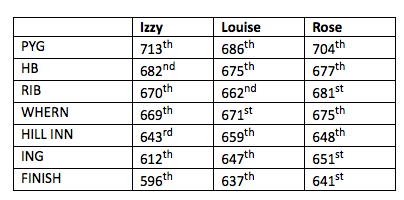

This year I remembered to take my ID to registration. I remembered to put my bottles in the right tubs, one for Ribblehead and one for Hill Inn, unlike last year, when both ended up at Hill Inn. I managed not to complain that the t-shirt that was meant to be teal was instead a more boring sky blue. I wandered around and chatted to folk, including my fellow Run Bravers Izzy and Louise.

This was Izzy’s first time running the race, and Louise’s second. I was sure they would both do brilliantly, having spent many Run Brave sessions running behind them wishing I could keep up. The rest of the pre-race passed as usual: toilet visits, kit check, race announcements (another improvement: this year everything was audible), more toilet visits, a warm-up. I was in a pretty bad state. My guts were a mess, and despite being considered an expert on shit and diarrhoea, to the point of being called the Poo Lady, I had no idea what to do about the fact that I was expelling nutrients at the rate of knots. The Poo Lady was the Clueless Poo Lady. My overwhelming thought was: I don’t want to do this. Really, that’s what I thought. I did not want to run 23.6 miles and had no idea how to do it. I was convinced, as I am convinced every year, that I would not make the cut-off at Hill Inn, despite all my training telling me otherwise. But I had my lucky socks on. I had my lucky nail varnish on. It would be alright, wouldn’t it?

And then it started raining, hard. Waterproof-jacket rain. Everyone gathered in the marquee and watched it. I think I thought, well, Three Peaks weather. But it passed quickly and that was the pattern of the weather set for the day: that old Scottish joke that if you don’t like the weather, wait ten minutes.

Start line.

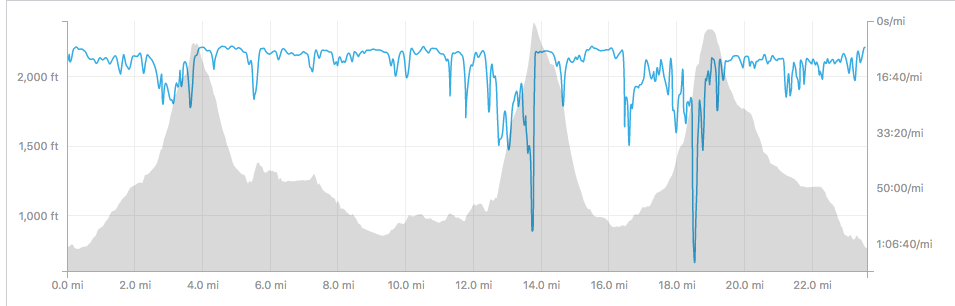

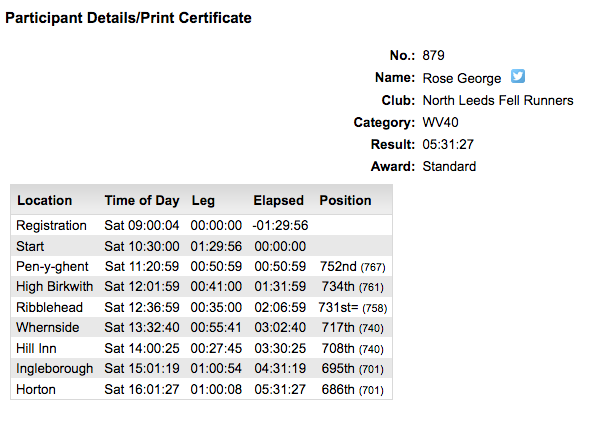

I went to my place, behind the 5 hours mark. My personal best on the Three Peaks dates to the second year I did it, in 2017, when I got round in 5 hours, 23minutes and 30 seconds. In 2016, I did 5:24.10 and in 2018 5:31.27. This year I was going to do better. Not by much, in the scheme of things. At least, it won’t seem like much to faster people. But I wanted to get round in 5:15. I wanted to get to Ribblehead in two hours, as I’d done on a recce with FRB in March. I wanted to have time to spare at the top of Whernside to know that I would definitely make the cut-off at Hill Inn of 3 hours 30, and not have the usual panic-stricken descent down Whernside. I knew anyway that it is difficult to gain any time on the descent because it is busy and rocky. This year huge new slabs had been installed on the path that when we ran past them on a recce looked like a giant had flung them to earth just to trip up humans so he could eat them more easily. There were no instructions this year to stick to the path or risk disqualification. I noted that.

Mingle, mingle, and then we’re off. I had two main points in my race strategy:

- Run more, not necessarily faster.

- Don’t set off like an eejit.

I knew I had got the second part wrong when I’d already got over the bridge and FRB came up behind me. Oh. I’m definitely going too fast. But I felt good so I carried on. I’d thought about not wearing my watch, as we had been doing training sessions running on feel, and I thought that would remove a lot of the stress I feel in this race. But FRB advised against it. You want to know where you are, he said. So after a while I turned the watch face to the inside of my wrist, and checked it only at the top of Pen-y-Ghent, at High Birkwith, at Bruntscar at the bottom of Whernside, and at the finish.

Louise and Izzy caught me up after a mile. I was worried by this: I’d clearly been going too fast. But I didn’t feel like I was straining myself to the point where I would blow up after Ribblehead. I don’t remember the weather being bad but pictures show different. Apparently it rained quite hard but I’ve forgotten that. Perhaps it was because of the clag that I fell over just after the hairpin bend on the path and smacked my knee on a rock (or perhaps I have a quota of at least one fall per race and had decided to get it over with). (Fall-running.) It hurt, and briefly I was worried, but I kept moving and the pain subsided. I didn’t notice that I’d opened skin on my hand and wrist, and injuries that don’t hurt don’t matter.

I got to the top of the mountain in 48 minutes. That was OK; I was aiming for 47. Then the lovely descent. I do this race again and again but when I think about it, I can’t think of any parts that I truly love. I find the climbing hard and I’m not quick enough at it; I don’t have the tempo to feel comfortable about the 6 miles to Ribblehead, Whernside is a slog, the Whernside descent is pure panic. I usually like Ingleborough because the pressure is off. This year though I meant to keep the pressure on, because I knew I could make up time by not walking the whole way to the Ingleborough climb, and by running more inclines. But I do love the Pen-y-Ghent descent. At first it’s soft and quick, then more technical but runnable, and as if you’re on a bicycle, it gives you momentum to get up the incline towards Whitber Hill.

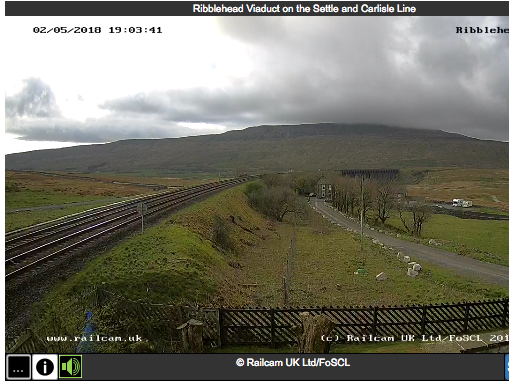

My plan was working. I stayed at a comfortable pace but pushing it, and got to High Birkwith faster than I’ve ever done. The weather had softened once we’d got off the top, and it was pleasant: a cool temperature, no rain. But there was a strong headwind along most of the six-mile stretch to Ribblehead, which was challenging. But once again loads of Leeds friends were marshalling and supporting, so many that fellow runners thought I was famous. “No, I’m from Leeds.” At one point I was crossing a grazing field with Izzy and she said, “it’s so beautiful” and I was slightly ashamed, because I’d forgotten to notice. Most of the time I’d been looking at my feet. So I thanked her for reminding me, because it was beautiful, even with dark skies ahead and more looming weather.

Everything was going well. I had fuelled where I meant to fuel. I hadn’t drunk much, but it wasn’t hot, so I assumed that was OK. (It was not OK.) I reached Ribblehead in 2:02, the quickest I’ve ever done. The final mile down – and up – the road to Ribblehead is always testing and peg-leggy (this is a technical term), and so is the tiny grass incline up to the checkpoint, but then it was over, I grabbed my drink, didn’t dawdle and set off again. I wasn’t hungry but ate a couple of pieces of veggie sausage on the way, because I always like to gird myself with salt for Whernside, where I once had fierce cramp at the summit.

Through the railway tunnel, and down to the beck, where I knew Harry Walker was marshalling. He won the race three times in the past, in 1978, 1979 and 1981) and Dave Woodentops Woodhead had taken a delightful picture of me with him and John Calvert (who won in 1976 and 1977) one year. I said as I went through the not-nailed-shut-with-pallets open gap in the wall, “you kissed me two years ago Harry,” and he didn’t remember, but his fellow marshal did. Actually it was three years ago, and he wasn’t the one doing the kissing so all is forgiven.

I didn’t get stuck in a bog this year. I planned to run more of the slog over to Whernside than before, and I felt good enough that I was sure that was possible. Then, a twinge in my right calf.

Oh no.

Another twinge, in the left. Right twinge, left twinge. I kept going, walking and shuffling. I thought if I ignored it it would go away. When that didn’t work I started to talk to my calves. Don’t you dare. Don’t you bloody dare cramp. Not here. Not yet. Please don’t.

But they did. And it was agony.

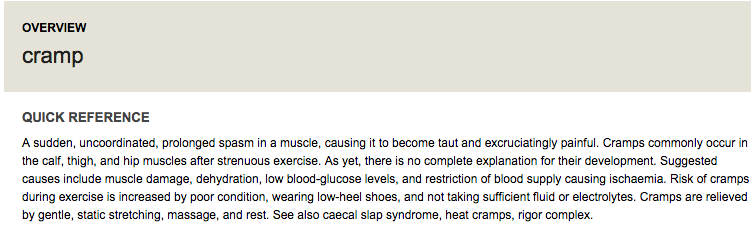

Cramps, say the Oxford Reference people, are relieved by gentle static stretching. Cramps are not relieved by attempting to run, again and again, while howling and whimpering and chasing a cut-off. I couldn’t understand it; I’d had salt in the sausage, I’d been drinking electrolytes, I’d only ever cramped after the steep Whernside climb. Some people say you only cramp if you haven’t trained properly, but that wasn’t the case (although as Coach FRB later pointed out, I hadn’t done many longish runs that contained the same mixture of climb, fast slippery descent and then a fast tempo). What was going on? I shouted at my legs. I tried to run but I had to turn the air blue, it was so painful. I thought, that’s it. My race is over. If I can’t run, I’ll never get to Hill Inn. I also had no idea how I’d do the steep climb if my calves were cramping this badly on a gentler gradient.

Then it started hailing. And I started laughing. Cramp and now winter? Really?

At the steep climb things got better. I could climb without cramping, which made no sense, but I wasn’t going to object, so kept going up the gradient, counting backwards in French as usual, going on hands and knees when it felt comfortable. Near the top I found Ollie, who was marshalling. He said FRB had gone up only half an hour earlier, looking strong (FRB later said that it was at Whernside he realised he wouldn’t get the PB he wanted of 4.20. He got 4.25 instead. Which was excellent.) At the top there was clag and marshals, and I set off hoping I wouldn’t cramp again. I didn’t check my watch because I didn’t want the stress. Luckily the weather meant it wasn’t quite as busy with walkers as it has been in other years. I don’t mind walkers and some of them are really cheering with their encouragement, and patient considering they have had to give way for 700 or so runners before I’ve come along. It’s the small dogs and children and walking poles that are troublesome. But this year there was no tape, which meant I could go off-piste and descend on my backside for some of it. No way was I going near those huge new slabs; they looked lethal even in clement weather. I did the quickest descent of Whernside I’ve ever done, and at the ice-cream van at Bruntscar I finally checked my watch while resisting getting a 99 with strawberry sauce. I knew I’d lost a lot of time to the cramped traverse to Whernside. It showed 3.16 (time elapsed), but I’d exactly calculated the distance to the checkpoint, and knew I could do 1.1 miles in 14 minutes. My brain said, “you could even walk a bit,” but I ignored it.

On the way up, the first “cut-off lady” man came up next to me again. I’d run with his brother for a lot of the way round, but had lost him on Whernside. He apologised if he had seemed rude earlier. No, just surprising. He said his name was Michael, and that he was about to retire and get the Bus of Shame because his legs were shattered. I said, please don’t call it the Bus of Shame, and then he told me he’d had a stroke two years earlier. So, I said, call it the “I had a stroke two years ago and I still did two peaks bus”. That might not catch on. Amazing effort Michael: well done.

In the end I got to the checkpoint at 3.26. That, for me, is good, though I’d have liked my watch to show 3.16 instead. I had interviewed Kerry Gilchrist, checkpoint leader at Hill Inn, for the programme, and we follow each other on Instagram but had never met. But there she was, and she said “well done, that’s stronger than last year.” There, also, was my friend Niamh, rushing towards me with a hug and saying “I’m so proud of you” which was lovely (as is her decision that she’s going to run it next year). There was Izzy, with her partner. And behind me by a minute or so was Louise. We’d all made it.

Now I was going to do better to Ingleborough. I wasn’t going to walk it all. I wasn’t going to get my usual adductor cramp, which I’ve also had every year, at the roadside stile that leads into the fields. I swung myself over the stile sideways, like a horse-riding gentlewoman, hoping to fool my muscles. For a minute or two it seemed to have worked and then it didn’t. This cramp was equally disabling, but it only lasted for one field. (At one point even my foot insoles cramped too.) Louise was walking ahead of me, but I began to run because I wanted to. I overtook her, and kept going, and everything was fine, all the way up to the steps. And the steps were fine too, up to the kissing gate, and then the hailstorm hit.

A proper hailstorm. Biting hail and fierce winds and I suddenly wished I wasn’t wearing a miniskirt but a million-tog duvet. It was like being pelted by arrows from a tiny army. Ow, ow, ow. I got very cold very quickly, and I realised I was getting to the danger point of being too cold to do much about it. I stopped and put on my jacket, but the wind felt like having my jacket too, and it took a minute or two. I didn’t really have a minute or two to spare, and this weather was really infuriating me. It took me another two minutes to get my mitts on. I don’t remember getting wet on the route but my other gloves were wet so it must have rained. Finally I’d got everything on, got up to the plateau and then my calves started cramping again. I watched Louise and her clubmate Tanya going off in front of me, and there was nothing I could do to catch up. It was a weird sensation. My body felt good and that I could run, but my legs were preventing me.

I walked all the way to the checkpoint then tried to run again and managed it. The weather was still awful. I wasn’t having a nice time – and I doubt the doughty marshals were either: thank you to all of you — and as I stumbled across the wet, slimy, slippery, rocky, risky plateau, I yelled “get me off this f*cking hill” at the sky, the weather, the elements. But the wind took up my words and the hail chewed them into bits and flung them back at my stinging legs.

I caught up Louise on the descent, and then my knee started throbbing, several hours after I’d bashed it on a rock three mountains ago. I couldn’t believe it. Partly it was because everything was starting to irritate me now: my big toe was sore, the soles of my feet were sore, I was furious about the cramp, and despondent, and now my knee. Louise very kindly gave me some paracetamol — I had some, but it was buried in my pack and me and my pack weren’t getting on too well — and she ran off (and got a splendid PB). And I ran on with a throbbing knee until it wore off. No doubt many scientists spend years working on the efficacy of paracetamol and working out precisely how long it takes to be effective. I can tell them: just under a mile. It felt like I was sluggish, but I wasn’t particularly, and still took places all the way back to Horton, as FRB later calculated.

The time passed, I didn’t fall over. I usually enjoy the run back to Horton, sort of. There are no more big hills, and the end is only five miles away. I recognised landmarks here and there, and I was looking forward to the rise of the land that would reveal the big white marquee far in the distance but not too far. I was fooled for a bit when I heard music and thought it was coming from the marquee, but it was a young lad in a walking group who had decided to blast out music that he probably thought was uplifting except he had chosen Queen’s “Another one bites the dust.”

There was plenty of dust still to risk biting, as well as rocks and pitfalls. But I stayed upright and finally reached that rise, then the gentle descent on gentle grass, then the final inclines. I’ve never run these all before but now I did. Nothing was cramping, the end was in sight. I refused to check my watch because I didn’t want to ruin my last few minutes by being disappointed. There suddenly were the smiling faces and cheering voices of my club-mates Hilary and Ann, who were marshalling, and I kept running, up and up through the field, keeping with a fellow in black with a leg tattoo who I’d seen frequently on the route.

He let me go ahead of him through the tunnel, and I put on a spurt and ran like I thought Coach FRB was watching (which he was).

And that was the end.

5.23.17

I got a PB of all of thirteen seconds.

Perspective: I ran through headwinds and hail and painful cramp and still made it through the cut-offs. I took places nearly all the way round. I should be proud of myself and eventually I will be. I was disappointed because I was fit enough to have done better. I’m disturbed that I got such bad cramp and don’t know why. Lots of other people did too, so perhaps it was weather and not drinking enough.

But a PB is a PB. And there was so much I loved about the race, in the end: feeling good for half of it. Seeing so many friends all the way around. Meeting people I’d run with before (a huge well done to Jacqui, who I ran with year, who smashed her time by nearly 30 minutes, and well done Heather). Beating my time last year by eight minutes, I suppose (I’m looking on the bright side). Doing all this while having spent the last few months fighting weekly bouts of depression.

Thanks here to all volunteers on race organization and on the course, for staying up for days to make sure everything went smoothly, for standing out on freezing hilltops in awful weather. Thank you also for all the wonderful support all the way round. It really matters. You know those machines that puff a little bit of air into your eyes at the opticians? Every cheer or smile is a little puff of comfort (without the blinking). Well done to my clubmates and Run Brave mates, who all did brilliantly. So did Cut-off Lady Man 2: he missed the cut-off last year but this year made it through, so his tactic obviously worked. Thanks also to FRB for being FRB and also for being Coach Run Brave, and being very good at it. He had a brilliant run, though he didn’t manage quite to match his time to his race number (420). Mine was 851 so no way was I trying to match that.

I am lucky to be able to run at all, and to live within an easy distance of such glorious hills and fells and tracks. Three Peaks race slogan is “the marathon with mountains.” It’s not a marathon, those may not be mountains, and it’s not a fell race either. But there is no race like it. It requires so many skills — pacing, climbing, descending, road-running, speed — and so much strategy, it counts as one of the toughest races I do. So I’m proud that that this nearly 50-year-old managed it. I’ll get my 5.15 next year, or better. I always say I’ll never do this race again so see you next year in Horton.