There are many Dodds. Watson’s, Great, Little, Stybarrow. I know their names because I learned them, and I learned them because getting them in the right order seemed necessary, when my nerves were skyrocketing in the days before the race. I had entered us — me and FRB — just after the Three Peaks, in a fit of ambition. Of course I then got a cold, something that apparently happens after you do something like running for 5 and a half hours up and down three peaks without giving your body fair warning. So once again (this is getting old) my training was substandard. I also had to fly to Denver and back in a three-day period. Dante’s Inferno is remarkably inventive: I won’t forget the people with their heads on backwards. But he didn’t include the particular frustration of being on the 31st floor of a hotel room in Denver with a beautiful view of the Rockies, and having no time or means to go to them. Instead, I managed an urban run along Denver’s inner-city rivers and creeks, which was fine but not much more scenic than the Leeds-Liverpool canal, though with friendlier homeless people. I wanted a flat run as Denver is known as the Mile-High City because it is exactly a mile above sea-level. Altitude training was enough without adding hills. I felt OK until three miles in when suddenly everything felt harder. Anyway, all good training, but not quite enough to ascend a very large hill and then get myself all the way to Helvellyn and back.

“It’s undulating,” said FRB. You just need to get up Clough Head, and then it’s….he didn’t say a doddle, but he didn’t make it sound hellish.

We decided to camp at Threlkeld, and found a site with a perfect view: Clough Head in front, Blencathra behind. We got there in good time and decided to have a leg-stretch and walk up to Clough Head. That does not mean we walked up Clough Head, that would be a leg-deadener. FRB was wondering about lines. These are what fell runners wonder about a lot: which line is best down or up a hill. The Clough Head fell race had taken place not long before, and there was a clear path, whether made by fell runners or there all along, going up the steepest part of the climb. We also had Alfred Wainwright’s book with us, and I had studied it carefully. It was my first proper reading of a Wainwright and I concluded that his writing is very good, and very grumpy, and quite funny. I can’t remember whether it was Wainwright or the wisdom of the internet (that is, fell runners who have run the race before), but there seemed to be an alternative way up and down. We walked up and had a look, and it didn’t seem to give much advantage. A runner passed us, quite slowly — it was getting steep — and with very little clue of the route. He said he was planning to run up Clough Head and along, the day before the race, and we nodded and wished him well, and thought, “lunatic.”

I don’t sleep well in tents and I didn’t hold much hope for this night, but I slept OK. We were up and away early the next morning, walking to the race HQ at Threlkeld under a mile away. The weather was fine, but the forecast promised wind on the tops. That was true, but not all the truth.

I did my usual race prep of milling and faffing. I remember the sun being so hot that we found one of the few bits of shade and sat under it, next to a man who had come from London only to run this race.

I was nervous. This was to be my first proper Lakeland race, and I didn’t think I was up to much. It’s boring to be perpetually worried about coming last, but I knew this wasn’t a huge field, which lessens my chances considerably. It was mostly local Lakes clubs, also known as the fast&thin&quick lot, though bolstered by an unexpected half-dozen of Hyde Park Harriers of Leeds, and the man from London. I also knew there were cut-offs, a fact always guaranteed to churn my brain.

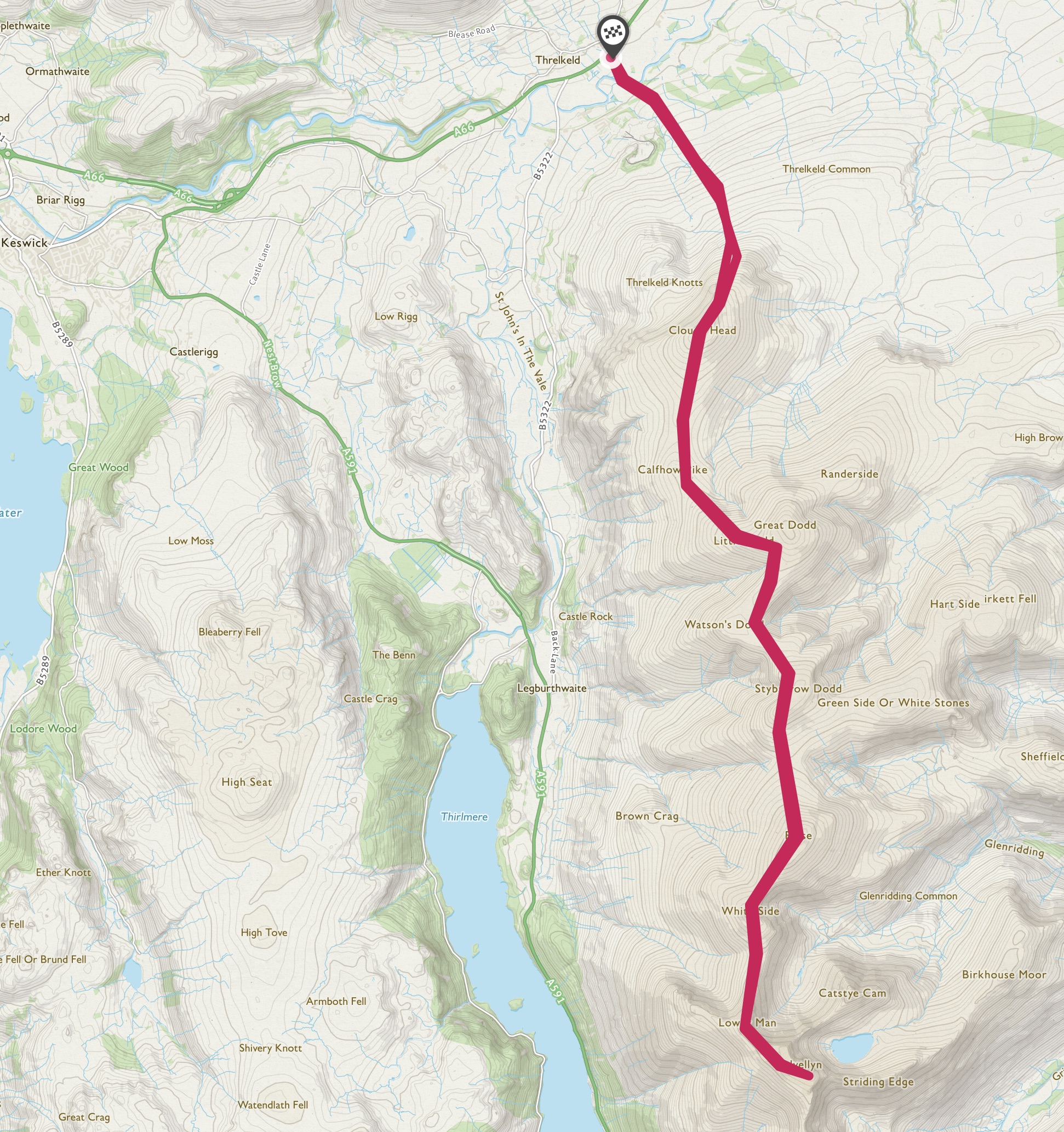

I had tried to learn the peaks in order, but I’m not one of those northerners who came regularly to the Lake District in my youth, and I can’t rattle off Wainwrights and put them in the right position, unlike plenty of my Yorkshire friends. The Lakes are a mystery to me. So, repeat after me: Clough Head, Calfhow Pike, Great Dodd, round Watson’s Dodd, Stybarrow Dodd, Raise, Whiteside, Helvellyn. Then back again. The final cut-off was on Raise, so I had to keep my mind on the route and count checkpoints and cut-offs.

We were told there was no water on the course, and it was hot, so I carried my usual amount: enough for a Lilliputian army. There were still people who were carrying no water though for 15 miles and 4500 feet of climb on a hot day. : kit checks were done, but water wasn’t a requirement.

We set off along a tarmac road, then up Clough Head. By “up,” I mean we climbed 1800 feet in about a mile and a half. I immediately abandoned all thought of good lines, and just followed the person in front, and got very very used to the sight of the back aspect of the person in front. I can’t remember how I got up, probably resorting to French as usual, but I do recall that at the top the forecast of “a bit breezy” became clear. And it became clear that “a bit breezy” meant “you will struggle to stay upright sometimes and the wind will never ever let up for the next 12 miles until you get back to Clough Head.”

And so it came to pass. I ran, I lost my map twice and recovered it twice from the pincers of the 40 mph winds. I gawped in astonishment at the eye-watering beauty of the views. I tried to do as instructed, and to put my thumb on the checkpoint on the map once I had got through the checkpoint, so I knew what was coming. This was slightly ruined by the wind nicking my map. At Stybarrow Dodd, I saw Graham, a friend from P&B, on his way back. Like many others, he had not gone up and over, but cut across a narrow grass trod along the contour. He recommended I go that way, so I did, without remembering that I am very bad with heights that are exposed: the slope was grass, but sheer, and a little nerve-wracking. This though was fine: as long as I can see what’s below and it’s not a sheer drop, I’m OK. The wind though was punishing and a little scary in its intensity. Also the noise of it: it’s only when it stopped that I noticed it had been shouting in my head all the way round.

At one point, of course, I lost track of where I was. I also thought I may be last. I’d seen some of the Hyde Park Harriers behind me, three or four, but they disappeared. I felt quite alone, and I was worried I’d be timed out. For a while I was convinced I’d gone the wrong way and missed a checkpoint and a whole bloody peak. But eventually I got to Raise, and I was in time, and then it was down to Sticks Pass, and soon up the rocky tricky climb to Helvellyn, where I saw FRB coming down on his way back.

You’d think there was a let-up in the wind, when I turned round for the return. No. On and on it blew. But I kept going, encountering a few other runners, including one lad from Hyde Park who said the others had disappeared because they were going to be timed out so he had left them. I don’t remember much of the way back, except that suddenly there was the checkpoint at Clough Head, and now I knew I had to find my way to a certain point on the ridge to get the best descent down, but everyone else was just heading straight down and I was so tired I thought, sod it, how bad can it be, and followed them. It was not the most relaxing of descents. Hard on the knees, hard on tired feet. But it was downhill.

Then to the tarmac road, where somehow my legs sped up, and around a bend and over a bridge where two women were cheering (thank you) and back to the cricket club where there was even some food left. Never has an egg sandwich tasted so fine.

I came 138th out of the 147 who got through the cut-offs. It took me 4 hours and 18 minutes, nearly two hours more than the first woman finisher, Hannah Horsburgh of Keswick. Bravo, Hannah.

I wasn’t last. Despite the best efforts of the wind, I loved it. See you again, Lakes.