Caussou. A place I had not heard of. A place many people may not have heard of as it is a small village on a mountainside in the Haute-Ariège. I have a house in south-western France, near the Pyrenées, and as we were coming on holiday for a few weeks, obviously I looked for a race to run while I was here. Trail de Caussou sounded perfect: 11km, about an hour’s drive from my house over the Col de Chioula, and organized by the village hunt committee. (This last part, as I am vegetarian and loathe hunting, was problematic. But not problematic enough for me not to enter.) It was a simple concept: you had to get to the top of Pic Fourcat and down again. FRB was not certain he would run, although he broke his injury and illness period by running Turnslack with me the other week. “Don’t be afraid if I fall behind you,” he said, and I nodded, thinking, that’s never going to happen.

I told him about Caussou and he looked it up. Rose, he said, do you realise the climb is almost as high as Ben Nevis?

No.

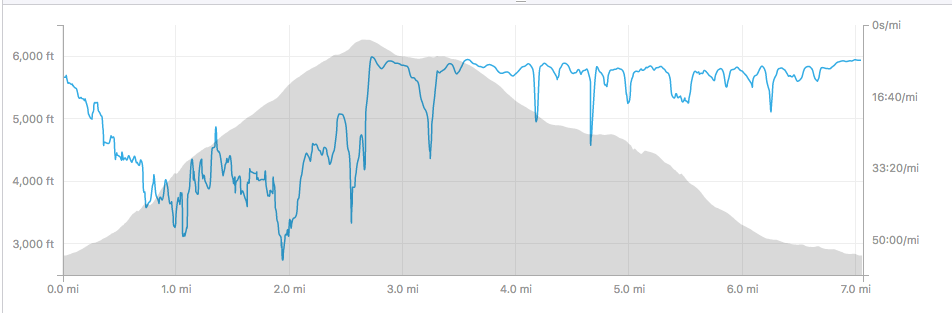

I looked at the race page a bit more. Caussou is at 3,000 feet altitude more or less, and climbing Pic Fourcat added another 3,500 feet. In my head, I retained this fact: we would climb for four miles and descend for four miles.

We drove 1,000 miles to France, arrived mid-week, and early on the Saturday morning set off to Caussou. I knew the way: up to the Pays de Sault, up further though the alpine villages of Camurac and Prades, up to the Col de Chioula pass, which has views as beautiful as the panoramic café staff are grumpy, and then turn right for a direct road to Caussou. We left plenty of time, because although I speak decent French, the website details were slightly unclear. Does “inscription à 8h” mean registration opens at 8 or starts operating at 8? I suppose I could have asked a French speaker, as despite the best efforts of English expats, the village where I have a house is still full of them. But I didn’t. Instead we allowed generous time. I checked Google maps and there were no traffic problems indicated. We got to the turn-off and there suddenly was a problem, unindicated by Google maps. The road was closed. In fact, there had been a landslide and there was no road.

Oh.

FRB managed not to splutter and so did I. I appealed to his Scottishness. “If we miss the start we can always run for free.” Caussou was already outside the FRB scale of race entries, as it cost more than £1 per mile. We went over the pass, down into Ax-les-Thermes and along the valley, then up again, adding about 40 minutes to our route. As we came off the main road, we encountered another car that had stopped to ask for directions. The man in in the car was waving his hand in what I consider to be a Gallic fashion to indicate frustration. (There was no signpost indicating Caussou, only a tourist sign for la route des crètes: the road of the mountain crests.) We saw his helper’s mouth make the form of “Caussou”, turned to each other and said “he’s doing the race” and followed him. This worked much better than trusting Google, because we got there. On a road that still existed.

Caussou is a tiny village high up and lovely. There were runners wandering up and down with numbers on, but also some without numbers who didn’t look panicked. From this I concluded that “à 8h” meant “from 8” and so it was. We produced our medical certificates, required in France if you don’t belong to the French athletics association, paid 14 euros, and received with grateful surprise a little headtorch, a very useful gift when you have a large 300-year old village house with a three-story barn attached and a leaking roof that tends to leak in the middle of the night. Back to the car and dis donc, suddenly we see a posse of Pudsey & Bramley runners. This was less surprising than it may have seemed; Gary and Debbie who run Pyrenées Haven are P&B, and we knew our friends Graham and Rachel had been planning a holiday there. There was also Niall, another P&B, who was accidentally still there due to a broken-down car and crap service from his insurer. If you think your car may break down in heat and mountainous terrain, or even anywhere, don’t use Axa. There was also another Brit, a Borrowdale fell runner. Out of a race field of about 70, six Brits was an impressive amount. I took appropriate pictures, one of which was photo-bombed by one of the organizers, a woman who managed to look like Maradona from behind (better than looking like him from in front).

The other runners looked like trail or mountain runners. Why do I say that? Because of all the poles. And all the compression socks. A Nordic walk along the same route set off at the same time as us, and for a time I thought all the people with poles were doing the walk, but they were runners too. I’ve never used poles, and I’m not persuaded, having seen runners clack-clacking up through forests no quicker than me, that they’re much cop. Then again, Ben Nevis.

We milled at the start, a fancy inflatable overhead thing from Decathlon (which sponsored the race) enhanced with a nice rustic touch.

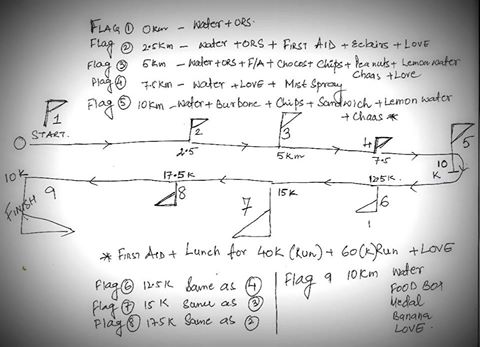

Someone started talking via a microphone but I couldn’t hear it. Typical fell race start so far. Then a pistol shot. Not a typical fell race start. I jumped half a foot from shock then set off. The up was immediate and it was hard. I only managed to run for a few minutes, and then it was a walk for the next 3,500 feet of climb. This means I got to know the runners around me. Walkers, really. We were all walkers. There was a young lass in front, and an old fella behind. We climbed up through some woods, a bit of open grassland then back into the trees. I don’t know how long it went on for but when I saw some people standing up ahead with food and drink, they looked like forest angels. I love French races for the refreshments: there were sweets, but mostly it was dried and fresh fruit. Dried apricots and cut oranges, but also prunes. Prunes? Fructose can cause digestive issues, but prunes are usually even worse. I took some apricots and a cup of orange juice, thinking, fructose, then thinking, SUGAR. I heard the older fellow say, “I’m going to be last again,” and I said, “you might not, it might be me, and anyway it doesn’t matter.” Because it didn’t. What mattered was getting to the end of this climb. Up again, through the trees.

The route was excellently signposted with strips of Decathlon tape hanging from branches. Even I couldn’t get lost. Even so, FRB said, check your map after checkpoints. I did. Once.

I checked my watch now and again. God, we’ve only gone a mile. God, we’ve only gone a mile and a bit. Finally we left the treeline and set off up an open expanse. This was felly terrain and familiar: tussocks galore. And the odd lonely tree.

I remembered to turn around to look and nearly fell over from the beauty and glory of it. Mountains, mountains, mountains.

Far up ahead I could see what looked like a ridge, but I told myself it was a false summit, it couldn’t be the real summit because this race was four miles up and four miles down, and we hadn’t yet done two. I looked behind me and saw someone I didn’t recognise. He was a young man, and he was climbing fast. When I next looked, he was even closer. It was like that scene in Princess Bride where Westley is climbing the cliffs of desolation. Soon enough he had reached me, and went past saying, “I missed the start!” He seemed to be making up for it.

I kept going, having a brief chat with the young lass near me, though I was slightly hampered by the following conversation in my head:

Should I vousvoie or tutoie? (Vous = polite version of ‘you’; Tu = more informal.) Italians much more readily use “tu,” the French more usually use “vous.”. Surely out here on a mountain even the more formal French wouldn’t use vous. I asked her if she was OK, using tu. She responded with vous.

Oh.

She said, using vous, that she had a made a mistake and should have carried water. As usual I had lots and gave her some. Using tu.

I looked up and saw folk on a summit. This was very puzzling. Perhaps there was another one to climb as well as Pic Fourcat? I got to them, not even managing to run for the photographer, and found the answer to FRB’s earlier question of “how will they get refreshments up without a road” in the shape of a huge quad bike, which had been turned into a serving table. Apricots, prunes, sweets, and flies everywhere.

I thanked everyone and set off as fast as my legs could carry me.

My legs didn’t like that. Think of a just-born calf, its upper body disconnected from the strange long things protruding from it. Gangly doesn’t cover it. My legs were moving but it was momentum not intent. It was not easy terrain to move fast over: grassy, tussocky, treacherous. Still, I ran as fast as I could. As fast as my legs could carry me. Then: halt. There was another incline ahead. Aha: there is another summit. But it was only a short incline. A woman with poles who I’d overtaken descending now overtook me on the climb. That’s fine, except I said hello to her and got short shrift so, as is the way of things in the runner’s brain, that meant: you’re not beating me. At the top of the incline I think there was a man with a clipboard, though perhaps he was a mirage, and then: DOWN. Five miles down. Because the race was in fact not four miles up and four miles down, nor even eight miles long. It was 3,500 feet of climb in two miles, then five miles back. I did my fell running thing and pelted. No-one else did: they seemed to have a steady pace that didn’t change much whether they were going up or down. There was no sprinting.

A short toilet stop in a prickly bush, a brief consideration of ticks, then I was off again. Again, it wasn’t easy. This was not a fair and spongy mountainside of easy running grass. It was rocks and narrow paths or tussocks. I have forgotten much of it, but I remember the next checkpoint. A young boy handed me a drink of water and though I still had some, I accepted it because mine was warm, his was cold, and he had plenty. I made conversation, asking the lad if he spoke any English. He lowered his head with shyness. No English, said the man on the checkpoint. Here we only speak French and Ariégois. He meant it jovially and I took it jovially. He also said, “be careful now; the path gets rocky.” I heard this, and thought two things: that “cailloteux” is a beautiful word, and, what, MORE rocky? And it was. It was properly tricky. I’d read an online piece about Kilian Jornet, who broke the Bob Graham Round record recently. It considered why he was so good, and concluded that it was because he was so fit, and so good at descending, that his descending was actually recovery. It taxed him so little, it gave him more strength for climbing.

I am not Kilian Jornet. This descent taxed me a lot. I rarely want descents to be over, but this one was exhausting. Boulders, pebbles, stones, rocks, dark woods: it had all of that. And my tired legs had to deal with it. I kept going, I managed not to fall over, and then got briefly lost in a dell, a fact I am not ashamed of as when I told FRB I’d got lost in a dell, he knew exactly where I meant. Oh, THAT dell.

I still thought the race was eight miles long, so when I emerged onto a grassy track and began to see barns and buildings, I was confused. Maybe they would stick another mile on it for fun? There was plenty of height to descend, as Caussou was up a mountainside. But then I saw the church spire, and I knew I was reaching the end, and that the race was just over seven miles, and that that was a blessing. Down into the village, past a few cheering folk. Bravo! Bravo! Past the lavoir, the stone washing basins where people used to do laundry, where I managed to note that runners were washing their feet and legs, round the corner and:

Fin.

The P&Bs were all long back, of course. I found a toilet first, then encountered the older man I’d been alongside early on, who was sitting down looking exhausted. He saw me and said, “I couldn’t catch you! I manged to stay with you up to the summit but then you set off downhill like a rocket!”. I thanked him and said it was due to enjoying descending and having little fear of it. Oui, he agreed. And you also have muscular legs. At least I think he meant muscular. He pointed to his lean ones. “Pas comme moi.”

FRB directed me to a water fountain gushing cool, lovely water. I drank some, poured some on my head, recovered a bit, then exchanged my number for a beer. I don’t drink beer, but this was delicious. It was still hot, so we sat in the shade before I remembered the lavoir and we headed for that. Two bored-looking firemen were standing outside it, on race ambulance duty. Someone said, there’s a giant catfish in there, and so there was. Huge, monstrous, and looking sad, unlike FRB, because beer.

What is a giant catfish doing in a village lavoir? I don’t know, but I didn’t like the thought of its teeth encountering my legs. Fish spas are disgusting even when they don’t involve catfish. I asked one of the firemen whether it was safe to bathe. He grinned. “Well, the other runners emerged alive.” Then, in English, “Trust me.” He was handsome and in uniform and wearing dark glasses, so I was minded to. But even so: it was a giant catfish.

We managed to wash while drinking beer, unscathed, then ambled back around for the prize-giving. I liked the look of this: there was an actual podium, which had been fashioned out of a tractor trailer that you climbed onto using a chair and the helpful arm of a nearby woman. The announcer’s microphone wasn’t brilliant though, but the prizes were. I’d seen them inside where the toilet was and wondered what the things that looked like hi-tech prosthetics were. Snow shoes! It was such a small field that the P&B lot were bound to get prizes, and they did: Rachel was 3rd woman, Graham got a Vet’s prize category. I didn’t expect to get anything: the results had already been pinned up and I was fifth out of five 40-50 women. But then, as I was making my way merrily through my second beer, I heard something like “ooze djoj.” None of the P&Bs paid it any attention. But I wondered, and wandered over to the announcer. Did you say Rose George? “Oui,” he said. “Ooze djoj.” I had no idea how, why or what I had won, but I remembered to put my beer to one side, climbed up onto a podium for the first time that I can remember, and was handed a shopping bag with a post-it on it: 3eme Master V1 F. Me! On a podium!

I got off the podium in one piece (I remind you: I don’t drink beer) and opened my shopping bag to see what prizes I had. This is what was inside:

- a bottle of foot deodorant

- a bottle of beautifying milk

- a hairbrush

- a plastic Sellotape-like dispenser that instead dispensed a bandage

- a packet of sweets

I loved it all. Especially the bandage, when I steam-burned my arm quite badly a few days later. The foot deodorant has come in useful too. But mostly, I loved the generosity of a small village race that thinks someone like me worthy of a prize. I worked out later that I had definitely come fifth out of five in my category, but the top two women had finished first and second overall. Impressive, and to my foot-deodorant advantage.

On the entry form, there had been an option to pay 15 euros or something to join in the village meal. I’d had small hopes, when the meal was arranged by the local hunt committee, of finding a good vegetarian option, so we had brought a picnic instead. We found a picnic table under a shady tree next to the village hall, where the meal was being held. I looked over the wall down into the garden where the food was being prepared: a giant hog roast, dripping fat into about two thousand potatoes. I went back to my bread and cheese with only a little bit of regret (I really love potatoes). After a while, a group of villagers came past, released from their race duties, and one shouted over, “aren’t you joining us?” We explained we had not paid, and were clearly picnicking but she was unfazed. “Come and sit with us anyway.” Which is why I love village races, hunt committees or not.

As for FRB and his conviction that he would be running behind me? He overtook me at the start and I didn’t see him after that. He told me he looked down from the summit and saw me in the distance and thought, “I’d better get a shift on”. He beat me by twenty minutes, but he didn’t win a hairbrush.