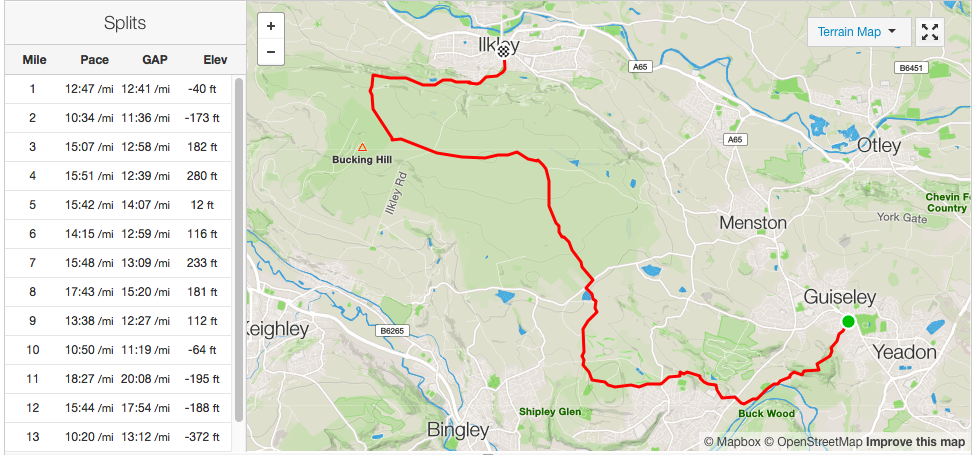

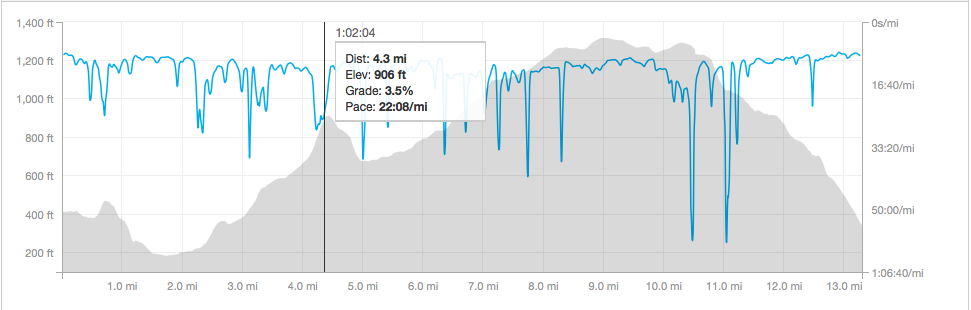

It’s almost time for Rombald Stride again. I loved it last year, and I will do it this year. But it’s 23 miles over moorland, and theoretically self-navigated (last year there were enough people around me that I only got lost once). So a recce – a reconnaissance run, to non-runners – is always useful, especially with my dreadful topographical memory. There was only one problem: haemoglobin. I gave blood again about two weeks ago. This time, after my last donation, I knew that my oxygen capacity would be affected for six weeks, not the 24 hours that NHSBT airily tells you about. But this time it seems to have been harder than before. It could also be due to the sertraline I’m taking, but I’m generally tired, tired and tired. I’m still running, but I have no oomph, mojo, zing or zest. I sleep a LOT. I don’t feel fit, though I am and though I can do what I did yesterday, which was run for 14 miles from Guiseley to Ilkley over the moors.

There were four of us: me, FRB, Tony and Sara. Sara used to be my pace but has got considerably faster, but she kept me company all the way round. It was a clear and mild day, though we all had full kit: a waterproof top and bottoms, spare mittens (some super lightweight gorgeous Montane ones that FRB got me for Christmas), drink, chocolates and mince pies. You never know what weather the moors will choose to throw at you. We were planning to stop for lunch in Ilkley afterwards, then get the train back to Guiseley. Bradford trains were still running; Leeds trains, because of the shocking floods, were not.

Sara hadn’t done Rombald’s before. I have, but can’t remember most of it. So we set off with FRB leading, trying to learn the route. McDonalds, first, for a toilet stop. Sara said, are we just going to use the toilet without buying anything? Hell, yes, I have no problem with exploiting McDonald’s. Then off, under a bridge, through a muddy field, up into the woods then down to Esholt. Guiseley hadn’t been flooded, and the field was wet but not flooded either. But as soon as we dropped down to Esholt, the water took over. The river was raging, and although it was clear some water had receded, by the rubbish and debris stuck to the fences like bizarre streams of bunting, we passed people who had just finished emptying their house of belongings. “You should have come past ten minutes earlier,” they said, and we said, of course we would have helped, that we were so sorry, then ran on. The lane became a small tarn, and to our right, a caravan park had become a lake with a few caravans peeking out of the water, like weird white islands. “Look,” said Tony, and we stood to stare at an astonishing sight: the mangled remains of a caravan, wrapped around a tree. I was shocked: I’ve seen all the streets in Leeds and York and the Calder Valley under water, and buses floating down streets, but this was the most violent example of the water’s power that I’d seen. And I suppose I’d better get used to it.

We ran on, up to Baildon moor, with its russet and brown gorse and heather, and up and over, past Sandy Gallops, the estate owned by Harvey Smith, a show jumper I remember watching on TV when I was young, then down past a reservoir, where we stopped for mince pies. I felt pathetic. My legs were managing to move, but not fast. Although, I had run for seven miles the day before, which probably contributed. But I was sluggish up hills and always, always glad of a walk or a stop. At the top of one moor, we stopped to have pictures taken:

As usual, the contrast between our clothing and what walkers were wearing – thick coats, hats, gloves, scarves – was funny. But I wasn’t cold, until the temperature dropped when we dropped down from Baildon Moor and up to Rombalds Moor. I could explain where that is by saying that Rombalds is part of Ilkley Moor, but actually Ilkley is part of Rombalds. It’s named after the giant Rombald, who was fleeing an enemy, stamped on a rock and formed the Cow and Calf. “The enemy, it is said, was his angry wife. She dropped the stones held in her skirt to form the local rock formation The Skirtful of Stones.” If that isn’t true, it should be.

On a clear day, it is a beautiful place.

There were other hills to climb, then rocks to descend, and trods between bracken. There were instructions from FRB to be remembered, to keep a wall on my right, or head for the mast, but I doubt I’ll remember them. I’ll follow the person in front on the assumption they know where they are going, which is a dangerous and daft assumption in a race. But it is what I’ll do. High on Burley Moor, we passed the Twelve Apostles, though I was so tired by that point, I’d have missed them if FRB hadn’t pointed them out.

Then there were flagstones across the moor towards Ilkley. They were long, long, long, and it was strange to run with such fierce concentration on my feet, so much that I went into a sort of trance. It was lovely.

I’ve probably remembered this in all the wrong order, but so be it. I do know that we ended up on the Millennium Way, and that walkers began to multiply, and were less bothered about saying hello – on the tops, everyone greets each other, in common sympathy at being insignificant humans in a wild place – and we stopped so that Sara could put on and break in my Montane mittens, because her hands were freezing. The walkers stared at the mud on our legs, which was significant. No-one had fallen, but there had been plenty of knee-high steps into black bogs. We reached the road to White Wells, and ran down into town, into another world of sale shoppers. I heard a group of young men say, “fell runners!” though I don’t know if it was with awe or disdain. We searched for a place to eat that would accept us in our muddy state, and found La Stazione cafe in the station, where FRB ordered a hot chocolate “with everything,” and I had a cup of hot tea and a toasted cheese sandwich and it was like a banquet.

I was slow, and it was hard, but I loved it. I went home and slept, and slept some more, and then some more for luck.