I rarely check the weather except through the window. There are two exceptions: when I want to know whether I can plant out seedlings, and when I’m due to run the Three Peaks race. Because this is what happened last year: snow underfoot, hailstorms, snow overhead, sideways. A blocked gate and a couple of minutes stuck in a bog. I didn’t want any of that to happen again. FRB sent me the link to the Settle and Carlisle Railway webcams: one at Ribblehead, which has a good view of Whernside, and another at Horton for Pen-y-Ghent. I became somewhat obsessed with them, checking again and again. And each time it was fair and clear and I checked the mountain weather forecast and it seemed perfect too: 5-6 degrees and very little wind. Without wanting to jinx everything, I thought: those are perfect conditions. Then on Thursday, with the race coming up on Saturday, I checked the Ribblehead camera. A blizzard. Seemingly heavy snow everywhere and still snowing. My heart sank even lower than its current I’ve-got-to-run-the-Three-Peaks position.

The next morning Ribblehead was clear and fine and lovely again. I put my weather worries aside and concentrated on the rest of things I had to worry about. Here are a few things that battered against the sides of my head from one bit of brain to another (that’s not scientific but it’s what it felt like).

Will I get round?

I won’t get round

Yes, I’ll make it

But I haven’t done all my training, I won’t make it

But I did the recces OK, I’ll make it

But I didn’t run from the start and I still only got up Pen-y-Ghent in 50 minutes so I won’t make it

But I’ve got a year’s more fell running experience, I’ll make it

But I have awful sleep half the time now, and I get bad depression days about six times a month, so I won’t make it

But I did it last year, I know what it entails, I have the mental strength to do it

But I won’t make it

But I did Baildon Boundary Way six minutes faster than last year and it was a longer and steeper course, so I’ll make it

But I inadvertently started tapering two weeks before the race and feel like I have lost fitness so I won’t make it

I can’t remember how to run so I won’t make it

My period – or the bleeding induced by taking progesterone as HRT – is due so I won’t make it

I can’t even conceive of doing the Three Peaks so I won’t make it

God, it’s exhausting being my head. On top of all that, of course, is the constant stress and workload of having to write a book by mid-June, which is not yet written. I was working long days at the studio, getting home late, eating and sleeping. I began training for this race in January. It’s the biggest one of my year so far. And I did my training if I wasn’t travelling or debilitated by my diminishing oestrogen (by “debilitated” I mean capable of nothing except lying in darkened room with my cat, because anything else made me weep). I’m not making excuses. They will come later. I made sure not to ask FRB whether he thought I would make it round, because I know that last year he hadn’t thought I would, or hadn’t been sure, and there was no point asking him when he would try to alleviate my fear by not quite telling the truth. But I did ask him about it, a few days before the race, and his answer was, “I don’t think you’ve done as many hills as last year.”

Tailspin.

Later he said, “but you’ve got a year’s more fell-running.” He said, “you have the mental strength to do it. You know what to expect.” Then, “I think you will make it round.” So back to my spinning head: I haven’t done all my training, but my times are pretty similar on Strava to this time last year. But, but, but, but.

By the Thursday night before the race, I’d finished working on two chapters, tidied my studio and told myself to forget about the book until Monday. I wanted to be relaxed on race-day morning, so, as we did last year, FRB and I booked a B&B. Last year’s was in Chapel-le-Dale, this year was a gorgeous place called Shepherd’s Cottage, off the road to Hawes from Ribblehead.

But first, there was the packing. I made a list. It was a long list. What happened to running being a very simple activity of putting a foot in front of the other foot? It included kit, shoes, watch, the obvious stuff, but also food for before, during and after, clothes for before, during and after. Things my addled brain is likely to forget, like my fell shoes or my watch. I dealt with this by writing WATCH and SHOES in capitals. I put on my lucky t-shirt and my lucky race nail polish. Everyone running the Three Peaks should do it with moral support from Snoopy and Woodstock.

I had worked out my fuelling: shot bloks, then solid food on the steep bit up to the road to Ribblehead, probably a marzipan ball stuffed with chopped nuts, which I made the night before. Then something savoury at Ribblehead while I walked and drank flat Coke, a shot blok at the foot of Whernside. Or something like that. I also carefully printed out the maximum times I needed to get to meet the cut-offs. 50 minutes up to Pen-y-Ghent, 35 to High Birkwith, 35 to Ribblehead, 50-55 up Whernside, 30 to Hill Inn. Hill Inn was my goal. Beyond that, I didn’t care what happened.

It’s curious that there are people who don’t have to have these considerations. They don’t have to worry about meeting cut-offs. It must be such a different race for them. I know that that is most of the race field and that I, and people of my pace, are the minority. For me, it’s three and a half hours of stress and worry that I won’t make it. I knew that I couldn’t do the PYG-Ribblehead stretch much faster than the cut-offs, because I’d tried it in recces and even when I’d belted it, I still only got to Ribblehead with five minutes to spare. Yet a fellow runner, after the race, looked bewildered when I pointed this out, because he’d never had to consider such a thing. I aspire to be fast enough not to have to worry about cut-offs, but I’m not sure that will ever happen.

Pre-race: chips, obviously. First, Billy Bob’s diner near Settle, where we ate everything. That’s Dandelion and Burdock in my glass. From a soda fountain. Which is about as classy as Yorkshire pop can ever get.

We checked in at the farmhouse, which was definitely going to be quiet. Except for the 4,000 sheep belonging to the neighbouring farmer, whose son arrived on a quad bike, looking rugged with ginger hair. I have no idea how all Yorkshire farmers manage to look like they have arrived from central casting, but they do. I hope that ewe 970 found her lamb because she was making a right racket.

Then in the evening, we drove to Hawes and to the chippy. It was easy to find because there was a queue coming out of the door. Along the road, someone had parked his tractor while he went for a pint. (Yes, I’m making a sexist assumption but I bet it’s right.) Every pub in Hawes had a line of 4WDs or farmer vehicles outside it.

We tried to digest by walking around Hawes, then back to the B&B for some daft telly and a hot chocolate. The daft telly was the Hunt for Red October and before FRB conked out he quizzed me on who had played Jack Ryan (I think this was a hypnotism technique to make me fall asleep). I only got Harrison Ford. This is relevant, because overnight I had a spectacular stress dream, in which I couldn’t get to the race because I was stuck in an enclave in Andorra or somewhere similar, with Harrison Ford. I woke up with relief that I was actually in a small farmhouse on the Dales Way. Then I remembered I had to run the Three Peaks.

Even so, I was quite calm. But there was a problem: I had no appetite. FRB had ordered a full cooked breakfast, though with vegetarian sausages. He scoffed it. The thought of that made me heave. Eggs. God, no. I asked for toast, and accepted a croissant. Both tasted like sawdust and I had to force them down. In terms of ideal pre-race fuelling, I don’t think half a piece of toast, half a croissant and a Longley Farm black cherry yogurt really cuts it. I thought I would eat later before the race, but I didn’t. There was a lot I didn’t do that I meant to before the race, like really properly warm up.

But I’m running fast ahead of myself. Unlike during the race when I didn’t run very fast at all. So. The race field: we drove 15 minutes to Horton, paid the £3, were greeted by a young farmer, and set off to register. The weather was clear, warm, lovely. Pen-y-Ghent looked enormous but not covered in snow, which was a novelty.

I tried to register, forgot my ID, had to go back to the car to fetch it. In place of my brain at this point was a big pile of nervous mush. Not even Harrison Ford or Snoopy could have helped. It was lovely to see lots of people I knew: several Pudsey Pacers, and two of the three other Kirkstall Harriers who were doing it. Again, I was the only woman from my club to attempt it. This is a shame but I suppose me going on about how nervous the race makes me doesn’t help. Women of Kirkstall Harriers: If I can do this, so can you, so please do. Everyone seemed cheery and in good spirits. But my Yorkshireman running partner Sara was attempting it for the first time, and she seemed as nervous as me. There were several toilet visits, and I managed to expel a lot of useful nutrients and didn’t have the appetite to replace them, though I’d got some carefully buttered Soreen. If you are thinking of running a long and tough fell race, ensure to have carefully buttered Soreen and then not eat it.

I did some warming up behind the main marquee: dynamic stretching, opening my hips, sticking my fingers in my groin to space out tangled hip flexors. I’m a sight, me. There was a kit check. Mine was carried out by Brian, the man who had had to deal with Pallet-gate last year, when a farmer had blocked a gap in the wall and we’d had to wait several times. I reminded him that we’d shared a B&B, and he kindly pretended to remember, then offered me some extra brownie points for having a foil blanket and a first aid kit. This will seem excessive, particularly to the more macho fell runners, of which there are plenty, but me carrying a foil blanket and first aid kit had nothing to do with the weather. It can be warm, and you can fall over on the tops and still get very cold very quickly. And me with my falling over record… Also I would be useful if someone else fell.

We gathered in the marquee for race instructions. The race director saluted Stephen Owen, who died during Loughrigg fell race. 37 years old. Rest in peace Steve, you sound like you were a lovely chap.

Then we lined up, and I lined up where I belonged, back at 4-5 hours. (There wasn’t a 5-6 hours bit though my time last year was 5:24. They probably don’t want to encourage that.) A man wearing a Saltaire Striders vest came up and said, “Are you Rose George?” and he did that without looking at my rainbow socks — apparently the usual giveaway — so I was puzzled. His name was Darren, and he said, “you’re the reason I’m doing this.” We ran a lot of races together, apparently, but had never met, and he had noticed that our finishing times were usually within a minute of each other. So he read that I had done this last year and thought, if she can do it, I’m going to try. Which is bloody brilliant. You know how every time someone doesn’t believe in fairies a fairy dies? Every time someone says I’ve inspired them to try fell running or something off-road, a whole troupe of fell running fairies burst into life out of a cairn on Ilkley Moor to spill more inspiration on walkers, and the world is a better place.

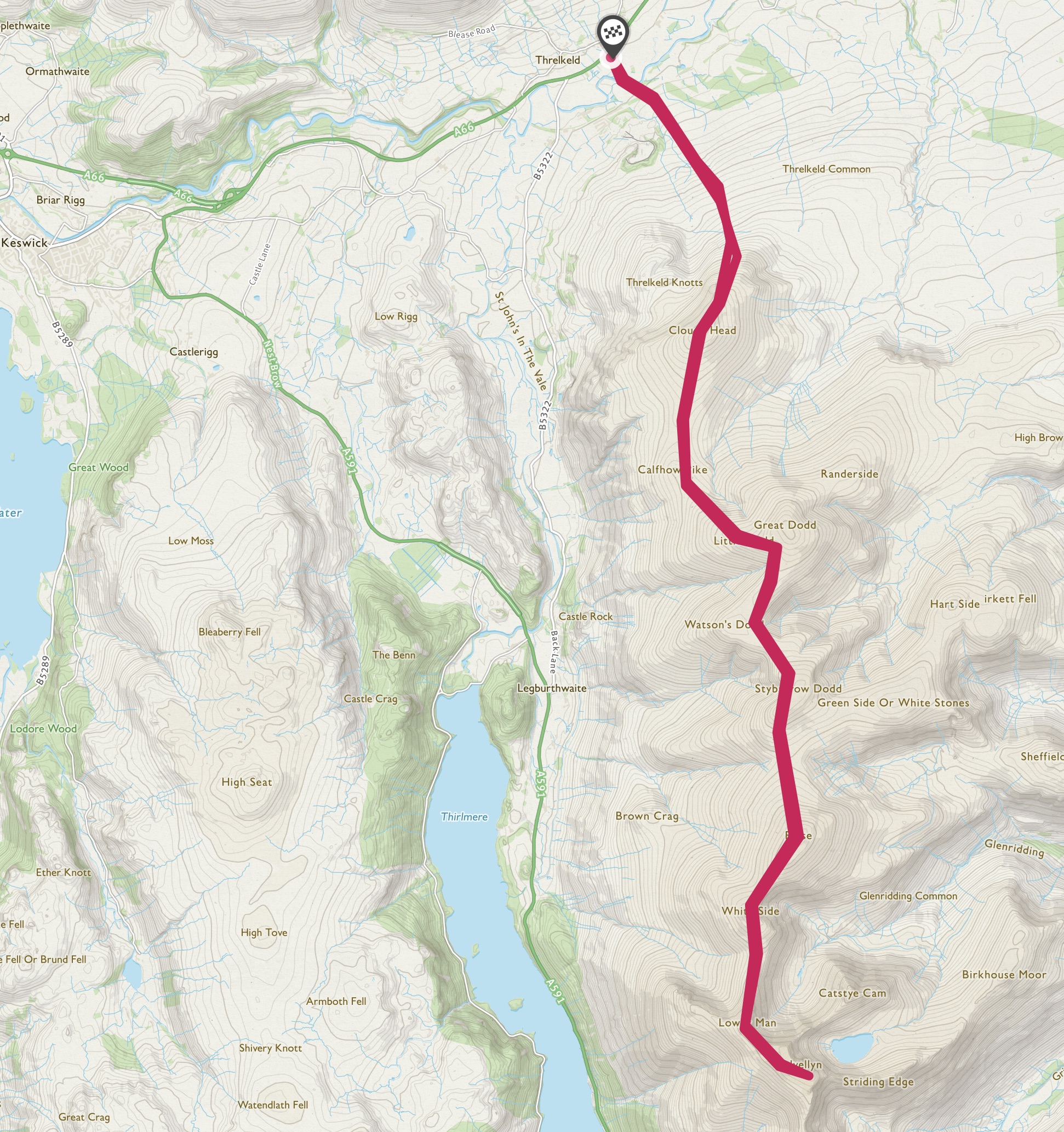

And then we were off, up the field, down the road, along to the track that leads up to Pen-y-Ghent. The hill looked magnificent. The weather seemed magnificent too: clear and warm.

I ran, and I felt awful, and I carried on running, and I felt awful. I felt really really awful. I couldn’t understand it. I began thinking negative thoughts, and then more negative thoughts until there was a big swirl of blackness in my head. I began to think I would have to retire after PYG. I thought there was no way I would make even the cut-off at Ribblehead. I had no energy. I couldn’t understand it. Was it because my period had started? Was it because I hadn’t eaten enough? Was it too warm? Maybe, yes, and yes. And perhaps I was just having a bad day. I started walking far sooner than I’d have wanted to. My friend Hilary is a fantastic climber of hills, and a few years ago did the Three Peaks in four hours something, which is the stuff of dreams for me. When we did a recce recently, she ran all the way up to the dog-leg, which will mean nothing to anyone who has not walked or run PYG. But it’s a long way up. I didn’t make it that far, not by a long way. I started walking much sooner and watched as Sara went on ahead, and there didn’t seem to be anything I could do about it. Eventually, the elite runners started to descend, pelting past us. I kept an eye out for Ben Mounsey, as he has always been so encouraging, and I wanted to cheer him on, as well as actually encounter him in real life. I’m not sure if seeing someone run past you at a pace of knots counts as meeting them in real life, but anyway: I cheered, and he was in some kind of extreme mental zone and I could have bashed a gigantic cymbal by his ear and I don’t think he’d have noticed. Possibly because he was finding it tough too, as his blog post says. NB I always cheer the elites and never expect a response. They seem like they’re in the same reality as me, but they’re not. Afterwards, when I was telling FRB how hard I’d found it, and how puzzled I was, he said: it was warm. It was really warm. Lots of people found it hard.

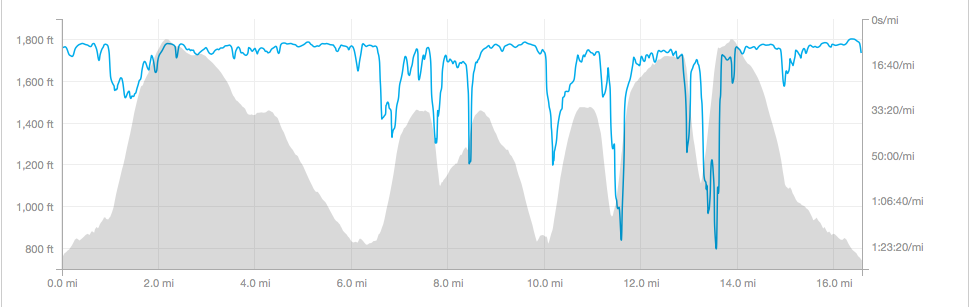

I did the only thing I could do, apart from stop, and ate and drank as much as I could. Two Shot Bloks, some electrolytes, some water. And I began to feel a bit better. In fact, my climb this year was pretty similar to last. Snow and ice or shitty nutrition and warm weather: same difference. At the top, I had got some strength back, and set off as fast as I could. I loved the descent: it’s off-piste at first, then on the path, but this year I could see where my feet were going, as the ground wasn’t snow-covered, so I could go off-piste more. It was great, but I knew that the section that made me most nervous was coming up. PYG to Ribblehead is about six miles, and the cut-offs meant I had to do it in an hour and ten minutes. 35 minutes to High Birkwith, 35 to Ribblehead. Last year I did it in 40 minutes and six seconds. This year I was three seconds slower.

I was on my own by now, having overtaken Sara on the climb. But first, there was Sharon and Caroline, two of my fellow Women With Torches, standing at the top of the first sharp incline after the bottom of the PYG descent, when you climb up to Whinber Hill. Sharon had been entered but had seriously bruised her ribs and decided not to run. Caroline is also a great fell runner, but when I’d asked her if she wanted to do 3P, said “No” with the finality of a glacier. I asked why not, and she said, “I don’t want to.” A very good reason. But they were both there cheering and being extremely supportive. I found it really welcome. Later, Caroline said, if I’d been a runner, and I’d just run up a hill, and it was hot, and these two loons were yelling at me, I’d have told them to sod off. Sharon took pics of me, including this one. I think I’d just said, “Try not to show that I’ve peed my pants”. Because no way was I stopping for a toilet and why do you think I always wear black shorts? And she didn’t. Thanks, Sharon!

They also took one of FRB (who had gone past many minutes earlier) who looked rather less sunny. Here by the way is his race report.

I got my head down, tried not to look at my watch, and ran as fast as I can. Then it happened again. A man I was running next to said, “Are you Rose George?” This time it was Colin from Clayton-le-Moors, who organises the Stan Bradshaw Pendle Round, a race I love. We ran and chatted until High Birkwith, which was manned by Pudsey Pacers, and it was very nice to see their friendly faces and get their encouragement. Thanks, PP. Then Colin looked at his watch and said, that’s great, we’ve got 15 minutes in hand. I didn’t understand that: in my head I had 35 minutes and we were on the nose. But I was seduced by this for a while, then sped up and got a shift on. My carefully laminated wrist band with all cut-off times, cumulative and clock targets? I’d lost it. Instead, marker pen and the bare basics:

I got to Ribblehead in 2:05. Not great, but quicker than last year. It only left me five minutes to spare, but even so I took my bottle of flat Coke and had a bit of walking and drinking (Thanks Andrew B for taking my bottle). I was pretty tired and Whernside looked bloody enormous, so I don’t even remember that Dave Woodhead was there. I’m very fond of Dave and Eileen Woodhead, because they are always cheery and encouraging. And also because even though I realise it’s difficult photographing an important race like the Three Peaks, because if you hang around to take the whole field, you risk missing the winners arriving at the finish. But Dave did hang around and took pictures of slowpokes like me, and I’m grateful.

So, Whernside. I always think of this as my favourite peak, right up to the point where I get to Ribblehead, gasping, and see it rising out of the earth like a gigantic, unsurmountable colossus of a mountain. It may be a hill, it may be a mountain. You all go off and argue about it. All I know is it’s bloody big. There was no pallet-gate this year, just Brian standing by the stream, and a beautiful gap in the wall that we all passed through as if by magic, or because three pallets hadn’t been firmly nailed across it. Whatever the race organizers did to negotiate with the pissed off farmer: thank you. (NB, he was probably pissed off because lots of people doing recces had gone through his private land.) After that, if last year’s race was any clue, there would be a few minutes of me being stuck in a bog. But no. I didn’t even see the bog. The ground was dry and mostly runnable. I always think of Whernside as being mostly about the steep climb up the face. But in fact it’s mostly the long slog across to the steep climb. I got up that by counting to 50, resting for 5, and on my hands and knees. Apparently people were shouting encouraging things from the top but I was in my own version of the Ben Mounsey zone at that point, and it could only include counting and zig-zagging and praying for it to be over soon. I knew that I needed to be at the checkpoint by 3, and I reached it in 2:57. My plan then was a helter-skelter down the path as fast as I could. Except, then:

Cramp.

I reached the top of the climb, and my calves suddenly turned into sticks of wood. I’ve only ever had cramp during a race once, and it was my adductor last year during the Three Peaks, going over the stile after Hill Inn. I had no real experience of cramp and had no idea what you were supposed to do with it. So I did a quick massage which made no difference and thought, right, I need to get down this hill so I’ll just have to run on it. I wasn’t the only one. I’d made sure to eat something savoury after Ribblehead but perhaps not enough. Luckily I hadn’t even seen that Ribblehead marshals were offering salt water. FRB took some and nearly boaked. Steve, another PP, took some and threw up several times. I understand why they were offering it, but salt water on a running stomach is surely never a good idea. The heat and dehydration and inadequate salt intake had had the same cramping effect on others: I saw several falls by people who, from their prone position said a) they were fine and b) it was cramp. What does running with two severely cramping legs feel like? Bloody weird. Like your legs don’t flex at all and you are running on peg legs.

It lasted all along the ridge and then tapered off. I followed the path down, unlike the race leader, hours earlier, who had gone off along the ridge in the wrong direction, lost his five minute advantage and then lost the race. When his sponsor, Salomon, later tweeted something that implied he would have won otherwise, I thought that was disgraceful. Fell running — though 3P is not really a fell race — is about navigation. The winner, Murray Strain, knew which way to go, and he won, and he deserved to win. Shut up, Salomon.

I quite enjoyed the descent, as the route wasn’t as taped as last year, and I wasn’t stuck behind walkers, and I could go off-piste. My toes were battered though. I was running in Inov-8 Roclites, which have grip and more cushioning than Mudclaws. But rocks are rocks, and toes are toes. Again, I thought I’d done the descent much quicker than last year, but I was only a minute faster. The brain is strange. I was busy calculating how much time I had left to meet the cut-off, but I couldn’t remember the distance between the various gates and Hill Inn, so I just ran as fast as I could. The answer came when I found Sharon, Caroline, Jenny and Dave again, who looked absolutely delighted to see me and shouted EIGHT MINUTES! YOU’VE GOT EIGHT MINUTES! and things like “YOU’RE AMAZING”. Thank you, Supporters of the Year. I heard this, and promptly walked for a bit, which is why I’m not an elite fell runner. Then I looked at my watch and thought, you stupid oaf, you have no time to spare, and got a move on. I got there in 3:26, five minutes quicker than last year, and was very very happy. Then I walked pretty much all the way to Ingleborough.

Why? I was tired. And my head was telling me that I’d done the important bit, and I wasn’t bothered about getting a better time than last year. Stupid head. Also, I got the same adductor cramp going over the same stile and it was so painful that I had to stop and yelp. Really. Yelp. But I kept going, sort of, shuffling along. I had no idea whether Sara had made it through, but just as I got to the limestone paving, she caught me up. Hurrah! I was delighted for her. She’d been convinced she wouldn’t make it when she’d had a bad race at Heptonstall so she’d done bloody brilliantly. And she’d fallen on Whernside and was bleeding from her leg and still made the cut-offs. True grit.

Ingleborough? Ingleborough is Ingleborough: rocky, steep, high. Near the top kids were handing out water and someone gave me a marshmallow, which was delicious. All the way round, the support was wonderful and I thank everyone who came out to watch, cheer, support, marshal, volunteer. Every friendly face, every cheer, every sweet is extremely welcome. On the way down and back to Ingleborough, I was worried that I’d go much slower as I’d run it with Dave Burdon of PP last year. In fact, I was faster. Along the way I came across a group of young lads, probably just teenagers. They were of the age you may be slightly wary of on a dark street in an urban setting, or the age that may heckle you when you’re out for a run. This lot were delightful: come on, you can do it, you’re looking great. I said, thanks, and I hope you attempt this one day, and I really hope they do. I said the same to two young girls who were equally encouraging, and I hope they do too. I often wonder what young girls and women think when they see me out running on the fells. I guess they think “she’s mad,” which is a reaction that drives me mad, when I wasn’t mad in the first place. I guess they also think, “I could never do that,” which is also wrong. And I hope they think, “I’m going to try that: it looks like fun.” Like the walker who was out when I was doing a Whernside recce recently, who saw me go off-piste and said, “that’s a great idea!” and followed me all the way down, running in his hiking boots. He got to the bottom a lot quicker than his mates and probably had a better time doing it.

On, and on, and on and on. I couldn’t remember if it was five miles or four to the finish. I’m not FRB, who knows every distance from every stile. So all I could do was keep going. This was peak falling period — tired legs, many rocks — so I had many words with myself, usually consisting of Lift. Your. Feet. Up. I kept penduluming with two lads, and we finally got the blessed sight of the race marquee in the distance, a large mass of white man-made materials in a green field that looked like the Promised Land. A final couple of inclines, up a field, then we were going under the railway line, we could hear the tannoy, we were through the private garden and past the chicken coop, and over the road, marshalled by cheery Pudsey Pacers again. I was just behind the two lads and I could probably have got a spurt on to overtake, but what’s the point? Instead I said, “Get a shift on!” to them and they did and I couldn’t catch them. I’d stopped looking at my watch but hoped I might do it in 5 hours 15, but I didn’t, despite FRB yelling from the finish line “TAKE TWO PLACES!” I managed to get a whole minute on my PB. 5:23.

This is where I have words with myself. I was very proud of myself for getting through Hill Inn five minutes quicker, but I’m bizarrely disappointed with a one minute PB, even when I told myself I didn’t care what time I did, as long as I got round. But I do care. I tell myself that with those conditions underfoot I should have done better. I tell myself I shouldn’t have wasted as much time getting up Ingleborough, nor taken my feet off the pedals. And then I think, I got severe cramp, I didn’t do all my training, I’ve done alright, I’ve run a race that hardly anyone in the country has done, that is usually describe as “gruelling” and I’ve done it while still dealing with the sodding menopause and all its accompanying debilitation.

I’ve done alright.

I’ve not done as well as I hoped.

But I’ve done alright.

I want to salute some people: FRB, who got yet another PB, this time 4.30, and did brilliantly. Andy Carter of my club, who did his first Three Peaks in a quite amazing time of 4.33. Sara, of course, who pulled a gritty and determined performance out of her bag. I’d quite like one of those bags. Me, for not falling over. Victoria Wilkinson, who broke the women’s course record by five minutes, which is simply astonishing. What an athlete. She’s going to be my fridge inspiration for the next year, because I’ve got plans for next year. I’ve had several days of feeling dissatisfied with my performance but now I think: I’m going to get better. Faster, stronger, better. You know how Nike is doing its Two Hours project? Mine is Five Hours. And at this point I must salute FRB again, because his careful, thoughtful training plans and coaching have been fundamental in getting me round both times. If you are tempted to try the Three Peaks, or any other big fell race, and want a coaching plan or a coach, he’s available for hire. Message me below and I’ll put you in touch. Meanwhile, for the Five Hours, stay tuned.

(Thanks Andrew Byrom for this picture. Hope you’re doing it next year?)

Image: FRB

Image: FRB