Ready?

Was I ready? I’ve been running but not sticking to a training plan since Tour of Pendle. FRB and I went to France in January and stayed fit, even while getting pickled on wine and over-carbohydrated with cheese and bread. We did some local runs, then got a couple of days in the mountains. In shorts, obviously. And I got to use the snow spikes he’d given me for Christmas.

They worked.

So I felt fit but I’d only done one long run — 15 miles to Harewood and back — since getting back. I did Tigger Tor race in mid-January: it’s one of my favourites and I did it last year after my series of calamities and falls. I did really well: I was nine minutes faster than last year. I enjoyed it and I felt strong all the way round. What does “feeling strong” in this context mean? It meant I ran bits I might not have: inclines I might have walked. It meant I didn’t feel like death at any point, nor like I wanted to sit down in the nearest bog. I had strength enough to do a 7.30-minute mile in the last stretch AND chat with people as I passed them (Yes, FRB, I know. I wasn’t running fast enough.) It’s a downhill mile of tarmac, but still. All in all, I was really pleased. Probably too much so.

The week leading up to Rombald’s I did three things: not much exercise, a lot of eating and a lot of checking the forecast. I did two spin classes, no running, and ate a lot of pasta and chips. I’m spending most of my days in my studio doing book rewrites and edits, so I was looking forward to the day out, even when the forecast looked like this:

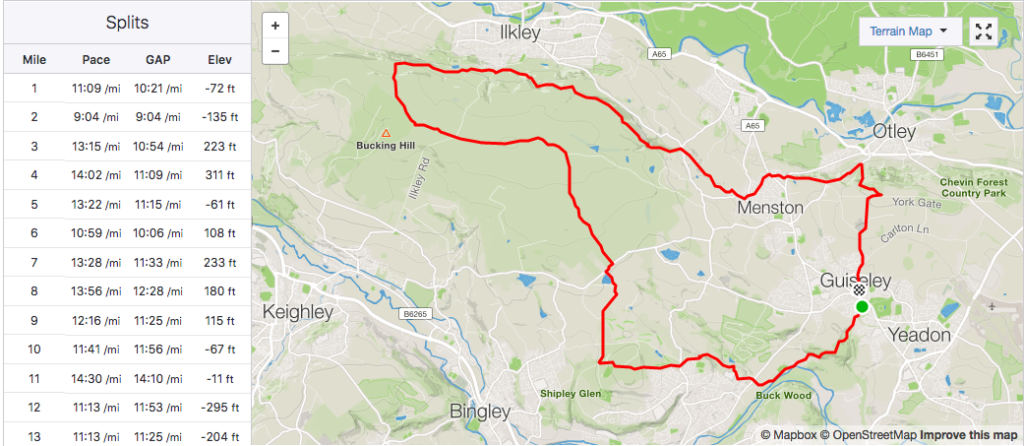

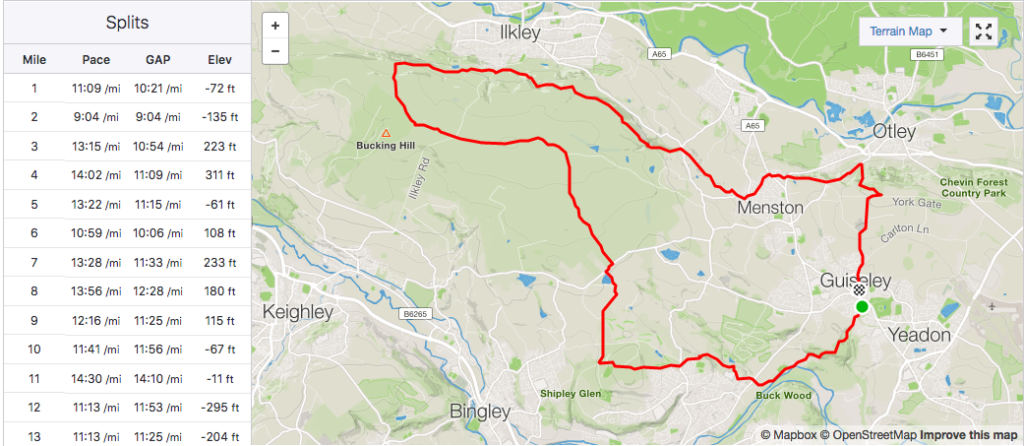

Sleet didn’t look like much fun, so I chose a merino top, vest, shorts and the usual socks. I carried an extra long-sleeve top and full cover waterproofs. Rombald Stride is run by the 15th Airedale Scout Group, and they don’t do kit checks, but I was going to be out in cold weather for several hours. I also had the usual picnic (chocolate, sweets, gels, veggie sausages) and a foil blanket. I slept well, and by 7.50am on Saturday was parked near St. Oswald’s Primary School in Guiseley, the race HQ, feeling nervous. About what? I don’t know. I was certain I would get round, because I’m stubborn. I really hoped I could do it in less than 4.30, because I’d done 4.15 in 2015, 4.28 in 2016 and 4.42 last year. I wanted to stop the slide. Of course conditions make a huge difference, but I’d been running well, I’d got significant PBs at Tour of Pendle and Tigger Tor, and I wanted to do well.

It didn’t quite go to plan. We mingled in the hall, I drank coffee, the air was the usual mixture of Deep Heat and hot drinks. I saw Bal, Carol, Vicki and Laura from Kirkstall. Bal and Carol were going to walk it — it’s a Long Distance Walkers event officially, and us runners have hitched onto it — and Vicki and Laura were going to run it. Or, in their words “we’ll have a shuffle round and enjoy the food. Rombald’s is great for food because there is usually lots of it. At other races such as the Yorkshireman, the offerings can be a bit sparse by the time I get to them. But because there are walkers, and because they have a cut-off of ten hours, all the checkpoints are laden with cake, sweets. And at one of them, vegetable tempura. Of course this would be the Burley-in-Wharfedale one, because that’s where I was once offered roast lamb or nut roast. I refused both.

I jogged to the start with Karen, a very fast and talented runner who ran it very fast and impressively, as usual, and way ahead of me. I knew that there were four North Leeds Fell Runners doing it, and we managed a nearly quorate team photo (I’ve never used the word “quorate” before joining North Leeds; there are a few lawyers in the club). It was drizzling, so most people had waterproofs on. We milled and mingled, then there was a klaxon and that was that. No race announcements. Everyone knew what was what: you had a token that you had to drop into a bucket at the first checkpoint, and a laminated race card, handed to you with a piece of string, that you had to get clipped or self-clip. Eleven checkpoints, 22 miles, 3500 feet of climb. Go.

I set off steady. This had worked at Pendle and Tigger Tor, so I thought it would work here too. For a while I ran with Serena, who I’d watched zoom off last year. She did the same this year and looked pretty strong, though she had been out with injury. I caught her up later though. The weather was fine, in that it was snowing persistently but not heavily. I like snow like that: the visibility is mostly OK and it’s refreshing. For the first few miles, I kept meaning to take off my waterproof but didn’t want to stop, and by then the temperature dropped along with the clag, and the waterproof stayed on. I felt really good. At the second checkpoint, I even took the short sharp climb up rather than the longer path, which I’d been intending to do. The first biscuit, a quick drink, a glance at my leg and no idea why it was bleeding, and I was off again. The next highlight was Sandy Gallops, where Harvey Smith had/has his stables. I love to cross a track and have to do the Green Cross Code but for galloping racehorses. One came past as I was approaching, but ambling, but then four came galloping through the mist and it was beautiful. What magnificent creatures. No, not the jockeys. I managed to take a picture which conveys nothing of the majesty and grace of racehorses but looks like a bloke ambling on a pony.

I passed lots of walkers and tried to say hello to all of them. Perhaps this was annoying: maybe you don’t want to say hello to 500 runners when you’ve got an eight to ten hour walk ahead of you. Sorry. I still felt good, enough to compliment someone’s dog and his beautiful blue-grey coat. “He’s changing colour,” said his owner and my running brain thought, wait, what, what kind of dog changes colour until I realised he meant from the bogs. Mucky pup. Up Baildon moor, down the other side, over more moorland. There weren’t as many spectators as usual, understandably, so I made sure to fervently thank the ones who had come out and who didn’t just cheer people they knew, including these two very encouraging and cheery women near Baildon checkpoint: Thank you.

I still felt good, though bogs do sap. I made sure to stop at every checkpoint because I was HUNGRY. Actual rumbling stomach. This was not how things were supposed to be. Hindsight: I should have had more to eat than two slices of toast at 6am. Even though I had something at each checkpoint, it was usually only a biscuit or sweets. I got my fuelling totally wrong. At Weecher, I set off walking because I can’t run and eat, and a woman came past. “Are you Rose George?” I said yes, and she shook my hand. This was unexpected. She hadn’t even recognised me from my socks, the usual tell (I’d already passed a man on a field who had looked at my socks and said, I read your blog!), but she had read my Tour of Pendle reports and was wanting to run it. We were running close by for the next couple of miles so I learned she’s only been fell running for less than a year. Of course I told her she can do Tour of Pendle (you can, Jules), and though she overtook me later and I didn’t see her again, I got a Ready Brek glow — at this point I could have done with some real Ready Brek — at what she’d said. If I inspire anyone to run even half a mile, I’m delighted.

I wasn’t feeling particularly inspirational at this point. Flagstones. I don’t much like flags. You’d think I would, as we had run a few miles of boggy ground, and flags are hard and visible and less trouble. And this year they weren’t icy either. But god, they went on, and on, and on, and on. I went into a trance to the extent that at one point I had no idea how long I’d been running on flagstones, and it seemed like it had been for much of my lifetime. Of course with the snow it made figuring out where I was harder than usual, which didn’t help the trance effect. It was beautiful, but it was long.

The bogs at the end of them felt like a relief, even when they looked rather snowy. Even when the marshals had written on the sign “Yes we know it’s wet.”

“Wet” doesn’t quite describe it. That wall stretching into the mist in the distance? That was the most solid thing for the next few miles. The bogs weren’t a relief. At this point my strength left me. I’d been running fine, and feeling good, and now I didn’t. I felt old and grumpy. The bogs were thigh-deep or deeper — FRB later said with decorum that he went “up to my knackers” in one — and it was hard going. I didn’t fall, but nor did I trip lightly over the ground and through the waters with fleet of foot and gossamer steps. Plod, plod, plod. Plod, plod, plod. Finally, some blessed descent, down to Piper Gate, over a stile on which some nice marshal had put a packet of sweets — and the marshals looked freezing and I wanted a magic tap of hot whisky to appear for them — then on to White Wells. Except suddenly I didn’t really know the way. I hadn’t done any recces, thinking running the race four times might count as knowing it. But I hadn’t counted on my running brain colliding with my menopause memory mixed with my verbal not spatial memory. Result: no clue beyond knowing Ilkley should stay on my left. I came across Aileen, an extraordinarily good veteran runner — she’s 66 — who was looking lost too, and with the help of walkers and asking HAVE ANY RUNNERS GONE THIS WAY a few times, we found our way to the Keighley Road checkpoint under White Wells. In fact we probably couldn’t have got lost: I knew not to descend to Ilkley and not to climb the ridge. But it still felt disorienting. I didn’t stop at the checkpoint although I should have: I was feeling sick and nothing appealed. I’d been looking forward to a cup of tea, but I didn’t trust my stomach.

Folk. Don’t do like I did. Eat when you feel sick. Something sensible.

I set off alone from the checkpoint. Other people were sensibly having food and drink. There was a man crouched above White Wells to support — thank you — but after that there was nobody. It was eerie to find myself alone amongst boulders and mist. The loneliness of the long-distance fell runner. Who was walking.

I was on my own for a mile or so, and I took it steady: I didn’t trust my feet not to trip on the rocks. I haven’t fallen for a good while but tired legs and wet rocks are not a great combination. FRB and I had done a recce at one point where we’d taken a trod up through the bracken and heather to the ridge, avoiding much of the treacherous slippery rocks. He’d advised me to do that, but at this point I had no idea where it might be, and I couldn’t see for the clag. So I kept on with what I knew: through Rocky Valley, cross a beck then turn right up through the heather to find Pancake Rock. It’s ironic that this stretch was where I felt most navigationally adrift, and it was the stretch where I was entirely on my own. At this point, I began to hear runners again, and turned to see them coming from all parts: high up on the ridge, mid-way up the hill, further down than the path I’d taken. I knew then I was OK and on the right track. The next checkpoint was a self-checkpoint at Coldstone Ghyll. I thought that was pretty soon after Pancake Rock, so I was alert. Of course it was actually about two miles off, and I’d confused one ghyll — a steep cleft or rocky ravine cut by a stream, according to Robert MacFarlane — for another. In Rob’s tweet about ghylls, he quotes Wordsworth so I will too:

I wandered where the huddling rill

Brightens with water-breaks the hollow ghyll.

I don’t know what a huddling rill is but after about 15 miles, I probably had one. I’d been penduluming for several miles with a couple of runners who were obviously running together. I’d seen them earlier, when they had yelled POTTER at Jules, then the male runner — Steve, it turns out — had had an entertaining thigh-deep encounter with a bog, and his female partner — Alice — had pealed with laughter. Which was nice to hear. I like running along and hearing laughter behind or in front of me, it’s like a bit of fairy fuel. Alice and I ran along together for a while, neither of us with any clue where the self-clip was. I thought the best thing to do was carry on in the vague direction of Burley. It turned up eventually, a scrap of ribbon on a wee pole in the midst of fog and snow:

I enjoyed the snow. It wasn’t hard enough to be blinding, and it was light enough to feel refreshing. Down, then to Burley checkpoint, my refusal of the vegetable tempura, and onto Menston. Now I was on sure ground. It’s daft that I run so often on Ilkley and Rombald’s moors and still get lost, but in a way that’s what I like about it. An enchanted moor that’s always changing (not really, but as it never gets fixed in my memory, it’s the same thing). But from here on in I knew the route perfectly. I was running with Aileen again now, and we compared stride lengths — really — and ran along companionably through the fields and ginnels and tracks. A man with a race number was standing expectantly on the corner of a street in Menston, clearly with no idea where to go next, so we guided him down to the hidden ginnel which was the next important junction, then waited for him about half a mile later, but when he didn’t appear, left him to his own devices. And hopefully a map. (This wasn’t cruel: there were other runners around him.) I wasn’t looking forward to the next stretch, as it’s a series of fields and several stiles to cross, which is not what your leg muscles require after 18 miles, then a long run down West Chevin Road, and then The Climb up to the top of the Chevin. I’d decided to wear Roclites not Mudclaws, as they have better cushioning, but I wasn’t sure how they would cope on The Climb, which can be a mud-slope.

It was a mud-slope. I’d had hopeful visions of me striding up it, but no chance. Instead, it was an inelegant scramble, trying to find patches of bracken on the mud that would give some purchase, grabbing on to any tree branch or sapling that looked sturdy enough. Of course I tore my legs open on brambles, but that’s a given. At this point I had no idea what time I was doing. I’d put my watch away a few miles earlier, because it was an added stress I didn’t need. I got to the top, and somehow my legs kept moving, and I tried to tank it down to Guiseley. There’s a half mile or so track though before the road down into the town, and it was more deep bogs and it annoyed me. I’d had enough of bogs by then. I managed to get up some speed on the way down, the usual dodging of bins and cars and people. Then, the roundabout and the last five minutes along the road, where you have to show that you are making an effort because there are people you know who have already finished who are shouting you in, and you have to earn the encouragement. Along the road, left into the primary school, into the entrance. This year, they handed out tags so it didn’t matter if you forgot to go up to the desk and check in, as I’d done one year. Finally I looked at my watch and I was appalled. 4.43. My slowest ever time. I went to find FRB and I was almost in tears. I can’t explain it. I’m not proud of this, but when he said he’d got a PB, I nearly burst out sobbing, and only just managed to say “well done.” I can only assume that on the way round I’d been putting myself under more pressure than I’d thought, and this was the steam coming out of the pressure cooker. Sorry FRB and well done.

Warm clothes, and then the traditional Rombald’s Pie and Boiled Potatoes, which always tastes as good as a school dinner would taste after you have run nearly 22 miles. Brilliant. Even the tinned fruit and cold custard.

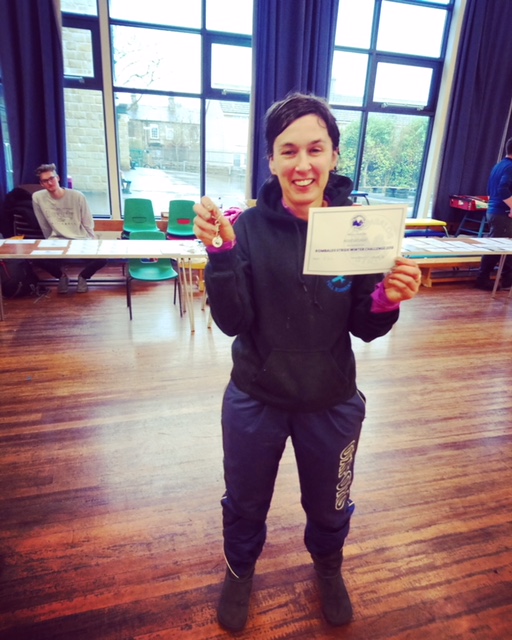

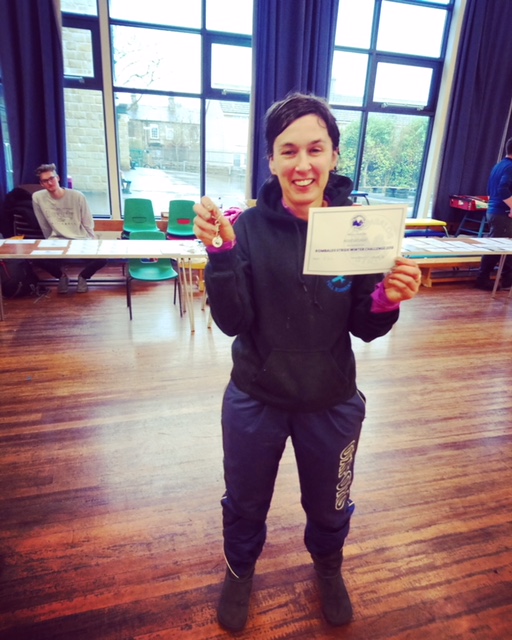

I slowly calmed down and got a grip. Then we collected our certificates and memento: a useful supermarket trolley coin and keyring. I’m not proud of my meltdown at the finish and actually I’m very pleased I got round. I really love this race and given my deadline lifestyle at the moment, I should have just focused on the fact I was getting several hours of running in a beautiful and beloved part of the world, and a month’s worth of fresh air. And snow. All that snow. I’m disappointed I didn’t do better, but I’ll treat it as an incentive not a sign. I’ll be back.

FRB gets his revenge at my churlishness by making me look like a Hobbit

FRB gets his revenge at my churlishness by making me look like a Hobbit