My friend Caroline left a comment on Strava: “rock up and do 20 miles, why don’t you?”

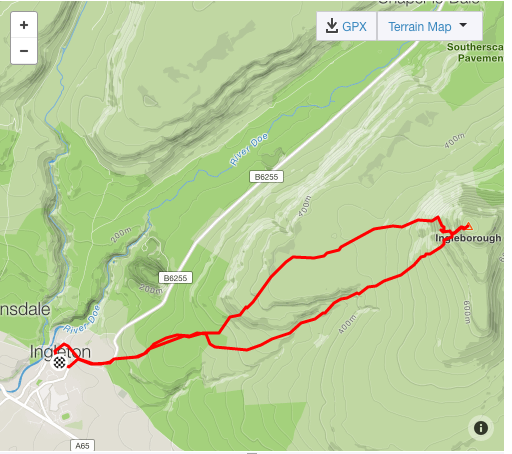

She was right. It can’t be anything other than rocking up when I didn’t get an entry until the Tuesday before the race on Saturday. Inadequate training is now a theme with me, but this was even more daft than usual. More daft than training for the Three Peaks with spin classes; or Tour of Pendle having done hardly any double-digit running for weeks?

Yes. Even dafter than that. Because this was a 21-mile race I’d never done before, that was entirely unflagged, that had only four checkpoints, and that I’d had no time to recce. It also had a small number of entries —- under 100 — which would mean a spaced-out field. At least the weather forecast was good. And as it was aimed at walkers and “non-competitive runners” too, there would be a) people out longer than me in case I got extremely lost and b) hot food no matter what time I got back.

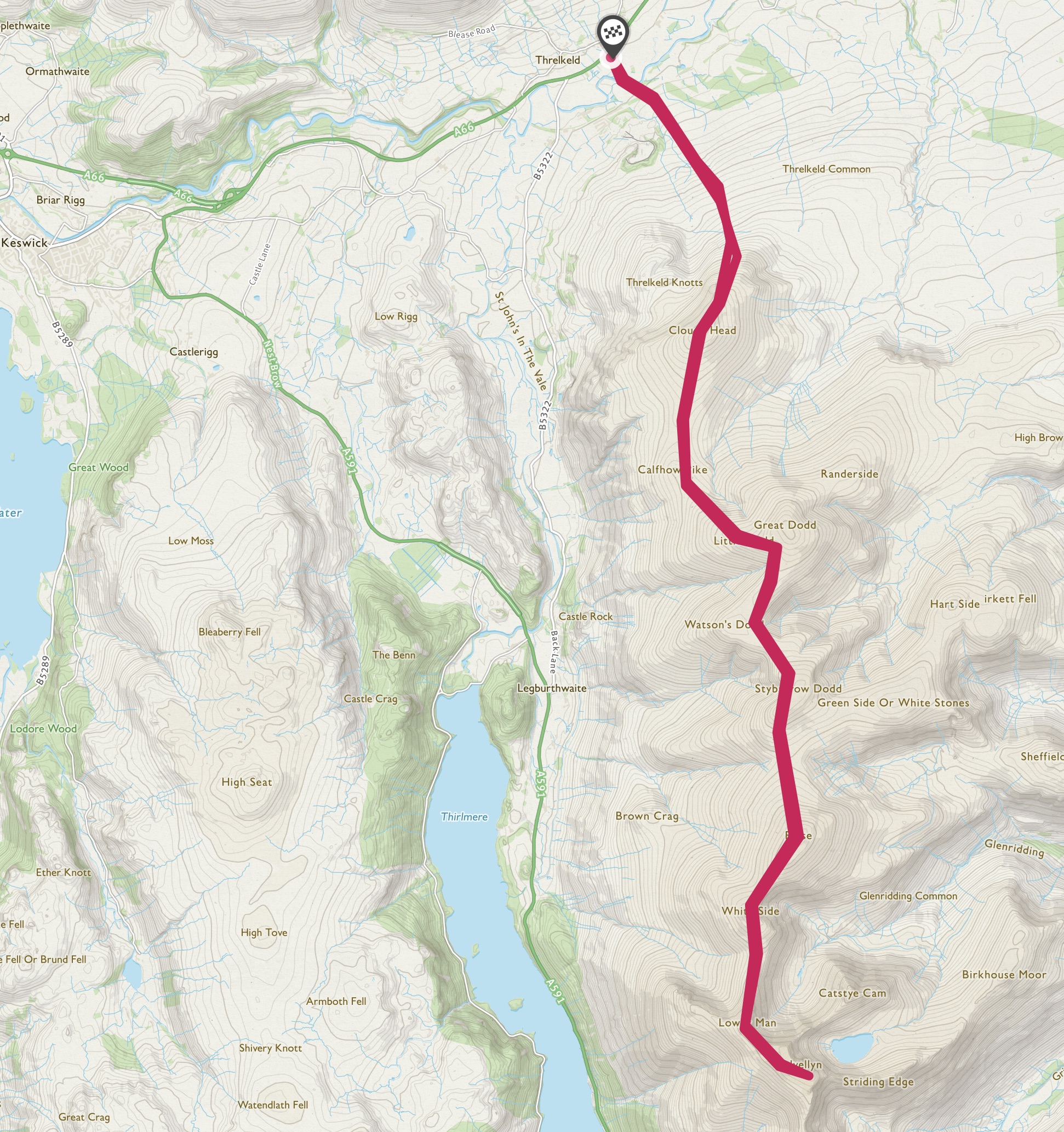

Moors the Merrier. I think it was the name that appealed. And the fact I’d never done it before and I have a habit of doing the same races each year, if the pandemic allows. My friend Louise told me about it. She had entered, as had Tanya from Fellandale. But then Louise fell and cracked a rib so the only person I’d know would be Tanya and although a few years ago we were matched for pace, that has long since been untrue. She stormed round Wasdale this year, for a start, with a fabulous performance, and she’s been running brilliantly. I’d be running around on my own.

I wasn’t sure how I felt about that. Four or five or six hours – who knows – of my own company? I’m good at solitude (writers are) but I also enjoy running with friends or making friends on the way round. It felt like it was going to be a very long day out. And it was a day that started early: the race HQ was Hebden Bridge golf club, high on the valley side, which meant a 6.45am start from Leeds. Of course the night before I was wide awake at 3am with a horrible restless leg, plus an equally wide-awake cat who thought it was breakfast time.

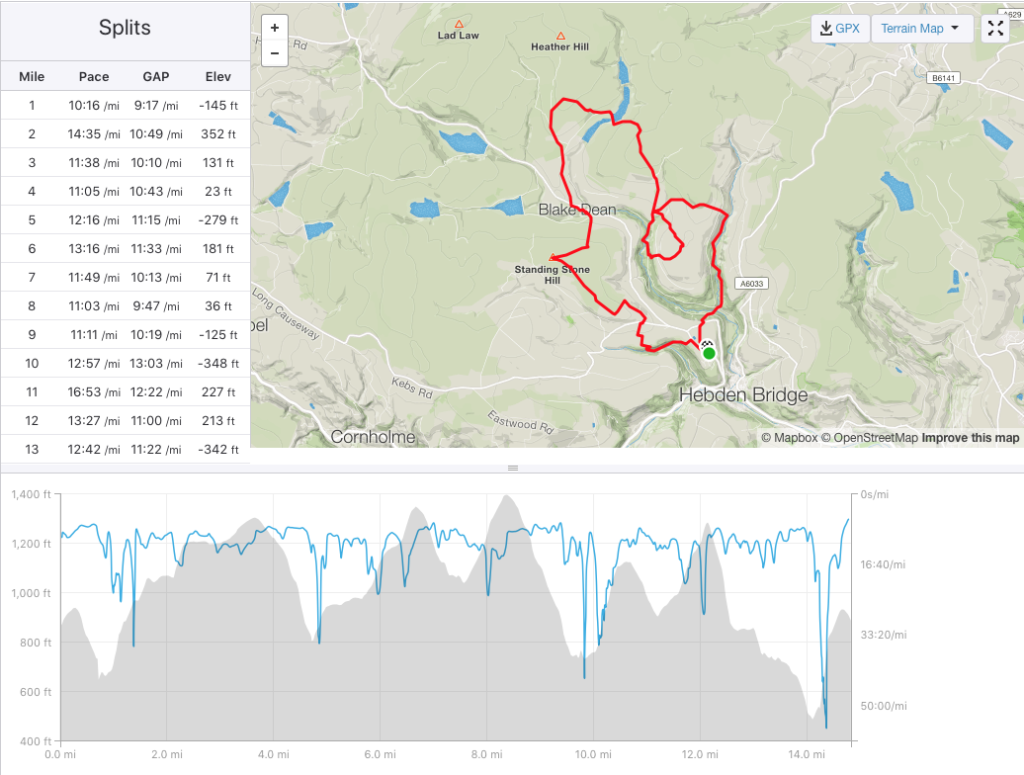

I knew where the golf club was as I’d run near it the week before doing Mytholmroyd fell race. I’d had a great day at Mytholmroyd: not that I’d won owt or got any category glory, but I’d taken places all the way round, felt strong, and finished by pelting down the steep valley side feeling like I was good at this lark.

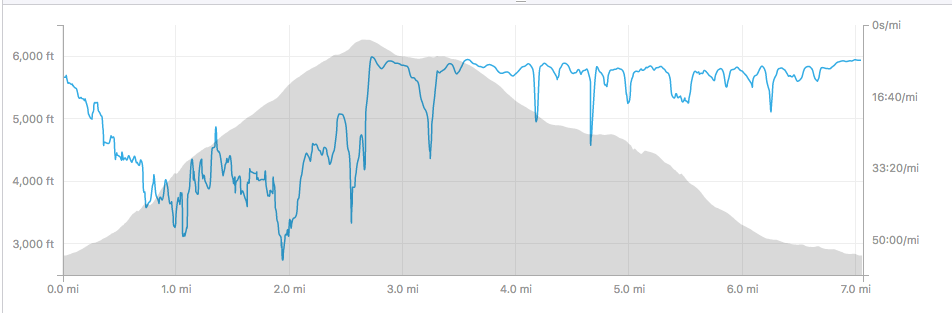

I’d also had a good run at Tour of Pendle, my birthday race. As usual, Kieran the RO had given me my age as my race number, a handy thing when you’re in the hinterlands between 50 and 55 and can’t quite remember how old you are when asked. I love Pendle, and this year I ran really well, right up to when the clag came down, as it always does, because the women hanged as witches quite rightly want revenge even when they were hanged miles away.

I followed someone who was following a GPX, missed the turn-off to CP11 and added half a mile to my route. I know that not by Strava geekery but because people I’d overtaken much much earlier were then ahead of me. Does that serve me right for passively taking advantage of GPX? Yes.

Anyway, Moors the Merrier. It’s run by Craggrunner, who also put on The Lost Shepherd, a cracking race. On this one there were two starts: 8 am for the walkers and non-competitive runners, 9am for everyone else. I wondered about the non-competitive bit. I’m competitive but I rarely get any category prizes. But if competitive means trying your best, then I was going to start at 9am.

The weather was clag and more clag. I got to the golf club just as the car park had filled up so parked along Heights Road. Darren, the RO, had emailed with copious instructions of where to park so as not to annoy bus drivers, along with this mandatory kit list:

- Santa hat

- Waterproofs (top and bottoms) with taped seams and jacket must have a hood

- Hat and gloves

- Map of the route, compass & whistle

- Santa hat

- Plastic mug for hot drinks on route (optional)

- Spare long sleeve top

- Spare food and drink

- Santa hat

- Survival bag

- Head torch

- Santa hat

I assumed the repetition was for emphasis, not that I needed to carry three Santa hats. So I gathered my Santa hat that I’d been given at the Stoop race, decided against my elf socks in favour of my usual mucky rainbow ones, and trudged up to the golf club. I’m fully in favour of rigorous kit lists, and so I had followed it to the letter, to the point where I could only fit one 500ml flask of water in my pack because of the survival blanket and extra long-sleeve and head-torch. So I was slightly disconcerted that the kit check consisted of checking that I had waterproof trousers, spare food and a headtorch and everything else was on trust.

We’d also been asked to bring a present, maximum value of £2, to “put in the bran tub.” I had no idea what a bran tub was but I brought a present anyway and put it in something that looked a lot like a garden trug.

[Update. Bran tub :“a lucky dip in which the hidden items are buried in bran.”]

There was no bran.

The golf clubhouse being a golf clubhouse, it was warm and comfortable. For fell runners without campervans who are used to car-boot/back seat changing this was luxury. There were changing rooms with lockers, though the solitary shower in the women’s was broken. If you’re desperate for a shower, Darren wrote, we can sort something out with the men’s. I don’t think any woman was that desperate, not when there were hot water taps and wet wipes.

I usually like to spend my faffing time in the car, but I wasn’t going to schlep half a mile just to do that, so I sat at a table with a cup of tea and watched the time pass. I was trying to understand who the crowd was. Wall-to-wall Inov8s, race numbers on chests, race vests, shorts = fell runners. Numbers on legs or — worse – racepacks, long tights, the odd Hoka = ultra runners. I know, how judgmental of me. But I’m not wrong. I decided this was a mix with the majority more ultra than fell. Not that it mattered, but it passed the time.

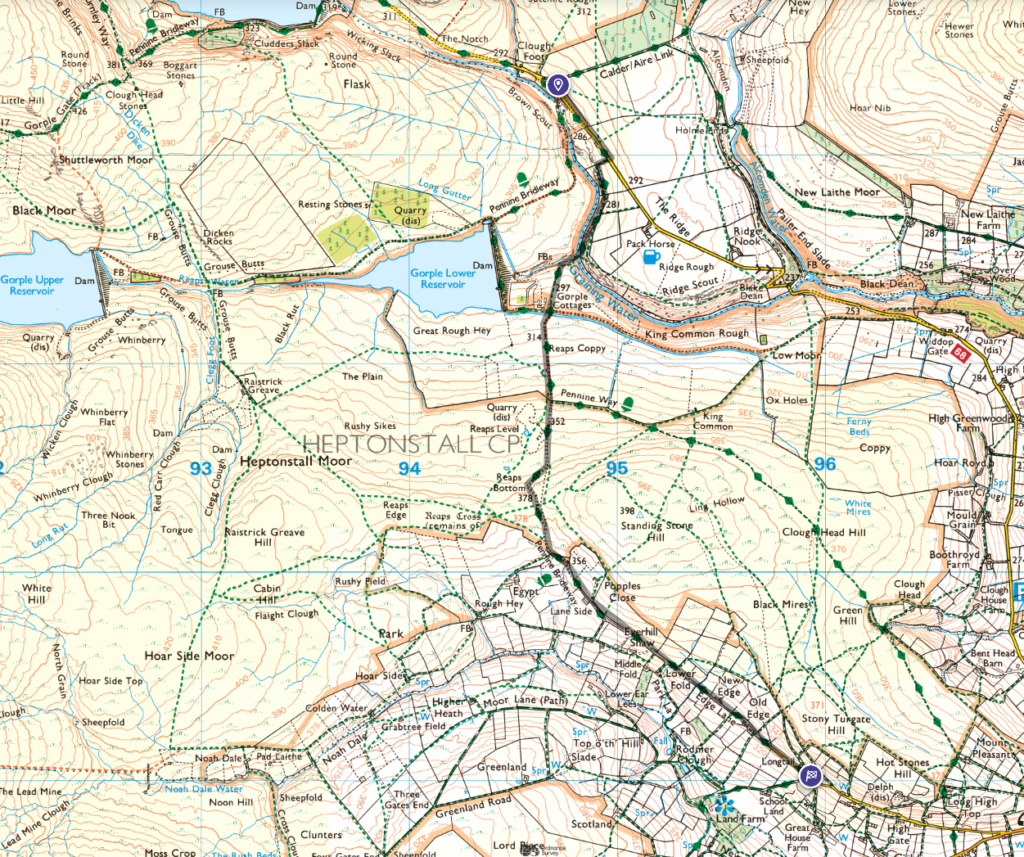

I told Tanya that I was worried about navigation. I’ve got a GPX file on my OS maps app, I told her, because it’s not an FRA race, is it? She put me right: on the notice board was a sign saying it was run under FRA rules. Oh. No GPX then. I’d drawn the route onto an old-ish OS map, and had printed out the pdfs on the race web page, though my printer had run out of colour ink. I would regret this later. I planned to carry the pdfs, 6 pages of them, swapping them around in the plastic folder so that I could keep my thumb on my position all the way round.

Faffing time was up, and we went outside. It was a small gathering of Santa hats, and very nice to see. The clag was still clag, but we set off, up behind the golf course and onto the moor towards High Brown Knoll, where I’d been seven days earlier, heading down to Mytholmroyd. I had my thumb on my map and would keep it there for 21-ish miles, and for a while I was really pleased with myself, checking off landmarks in the landscape and finding them on my map. Shaft, check. Sharp left turn, check. Climbing the contours, check. I didn’t need to do any of this, there were plenty of people around, but from Pendle I knew this could change very rapidly and I’d be reduced to squinting into thick fog trying to see if anyone else was going the way I was going. I realise this means I put ridiculous levels of faith in other people’s navigation. I’d also regret this later too.

Through the clag, I heard the booming Yorkshire tones of the one and only Dave Woodhead. You again! I shouted, as I’d seen him last week too. Dave and I yell at each other but it’s affectionate: I think he and Eileen are brilliant to be standing out in all weathers photographing just for the love of the sport. He was standing just by the trig pillar, and this was our conversation. :

Him: Stand over theere by the trig, it’s got a heart on it.

Me: OK

Him: Right, now bugger off.

Me: I love you Dave.

Him: Merry Christmas girl!

He’s a tonic. Onwards to CP1 on a main road. The clag was lifting now, I had people in front to follow, my thumb was on the map, I knew where I was and I could see the hi-viz of marshals in the distance. Number taken, then the marshal said what I thought was “have a good day” but actually he said “don’t forget to dib,” because I had. We had our dibbers on wrists attached by those tight papery straps you get in hospitals, like giant babies with tracking devices, set free from neo-natal cribs to lurch across sodden moorland.

Was this a fell race? It had plenty of off-road in it so far, but paths rather than trods. It was being run under an FRA licence which meant FRA rules, which meant you could make your way bewteen checkpoints as long as you weren’t flagged to a particular route or didn’t cross private land. But Darren in his setting-off announcements had said to stick to the route, so I was going to try to stick to the route.

Page 3 of my maps and bloody hell I recognised where I was. I expressed this delight by saying out loud “Nook!” which people around me wisely ignored. Nook is the ruined building on the way to Stairs Lane, last seen on the Haworth Hobble. I had no idea where we were going after that, but every now and then I’d recognise sections from one race or another. I think there were bits of Mytholmroyd, Haworth Hobble, Heptonstall (at one point I said to a woman running near me, “This is Heptonstall backwards!” and most bizarrely she didn’t respond).

It wasn’t cold, the forecast rain hadn’t yet arrived, and I felt comfortable. A woman ran up behind me and said, “I wish I’d worn shorts.” Only me and one other woman did. I answered with my usual self-critical, “My legs have plenty of insulation,” and she said, “that’s a magnificent pair of legs” and I fell in love with her immediately, enough that when she overtook me by climbing a gate instead of going over a steep and tricky stile as she should have, I nearly forgave her. Nearly.

I didn’t feel as strong as I had done on Mytholmroyd. I even looked at my watch, saw I’d only done 8 miles or so and thought, shit. I try not to watch-watch but for the next half a dozen miles I did, and it didn’t help. I couldn’t understand why I felt so tired.

I tried to chat to people to make the time go quicker, especially ones who seemed very confident in the route or had recced it. They were going to be my very special friends. If I’d been left to my own navigational devices, I think I would have gone wrong quite a few times. But perhaps I’d have been more rigorous than keeping a weather eye on my map. I’d already realised that black and white maps aren’t ideal: the colour gives clarity, particularly when the colour is blue and denotes big reservoirs that you can see with your eyes but not on the map. Except it actually was on the map because this is what this excellent navigator did: for an entire map section, I couldn’t understand where I was. My thumb wasn’t making sense. I was with people who seemed to know where they were going — no hesitation at junctions — so I wasn’t too worried, and by the time I was thoroughly confused by the disconnect between landscape and map, there was only a mile or so to the checkpoint. There was a reservoir in plain sight, but I couldn’t see it on the map. The trouble was that I was convinced that a section on the map was a bit we’d just come through, a clough with a beck and a bit of wiggling up the sides and then I tried to make the rest of the map fit even when it didn’t. And I put the missing reservoir down to my monochrome map. It must be there, I just couldn’t see it.

When I reached the checkpoint, then set off again sorting out my map pages so they were in the right order, I realised.

I’d been following the wrong map. I had been running along pdf number 3, and I’d been following pdf number 4. What a bloody idiot. The body of water that wasn’t? Perfectly present and correct – Gorple Lower Reservoir – on the right map. I suppose if you are keeping your thumb on your map it helps if it’s the right one.

I swore to pay more attention, and keep my compass to hand.

By now there were 3 or so of us who were running near each other, sometimes overtaking, sometimes retreating. There was an older man behind me with a full OS map. I mention that because for some reason my brain told me “ full OS map means he knows what he’s doing.” He was one of the people with his race number pinned to his racepack, and on one climb I asked him why. “Because if you change your top you don’t have to faff around changing your number.” Oh, I said innocently, but I thought it was against the rules? “Well,” he said, “no-one has bollocked me yet.”

Plenty of people were using GPX too. I didn’t, but I benefited briefly when we ran a section that I recognised though god knows which race it had been a part of. (I’m going to go with Lost Shepherd.) This took us down through more bog, no paths in sight, and the map route ended with another wiggle, only we got the wiggle wrong, and only a man with his GPX put us on the right direction. At that point the route headed due east, no paths, and I got my compass out and used that. We’d passed Lumb Falls early on; now we were heading into another dell with rushing water and slippery rocks. None of this was familiar but it all looked like any other dell with rushing water, woods and rocks: Hardcastle Crags, Lumb Falls, anywhere. I should point out that it was beautiful even if my eyes were mostly on my Mudclaws.

On the way to the next checkpoint I saw a man ahead carrying a huge log on his shoulder. I thought it was a local carrying some firewood – a lot of firewood — until I ran past him and saw he had a race number on his shorts. “Are you doing this for training?” I asked. Yes, he said, I asked no more, we wished each other a good run or walk, and I headed to the checkpoint for a cup of tea. 15 miles in, nothing was going to surprise me.

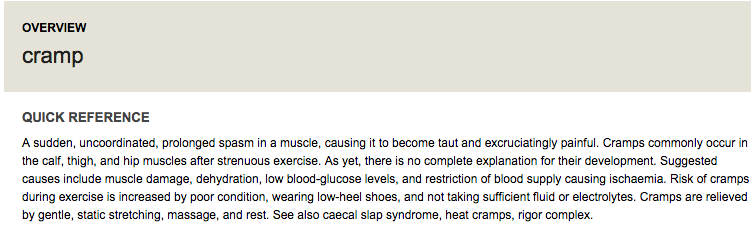

By this point I should have been worried. I hadn’t even drunk 200ml of my water, and looking back I was definitely dehydrated. I hadn’t fuelled much either: a couple of gels, a quarter of a Snickers, and a small wrap with hummus does not consist of adequate fuelling for 5 hours on your feet. But it was cold enough that I didn’t feel thirsty, and I wasn’t hungry either. Daft. And it explained why I was so tired, along with the energy-sapping bogs, bracken and soft fields.

Burnley Road, over the other side, and up into the woods. I passed caber man again. “Are you fundraising?” “No.” “What does it weigh?” “30 kg.” “Right.”

The route showed zig-zagging switchbacks all the way to the top. I was on my own, with the OS maps man behind me, and I carried on the main path, not exactly confidently, but not feeling like I was going wrong either. I saw two women with race numbers walking down below and got thoroughly confused, and still don’t know where they were going. I carried on upwards, thinking, it should be switchbacks but it will turn back on itself soon. I also thought, as long as we get to the top and I head south, I’ll be fine.

So I carried on, past two lads on motorbikes who said “is it a sponsored event or something?” and along a decent path (the Pennine Way) that ended at a gate. I could see Stoodley Pike up ahead, and I was pretty certain that the route contoured around a hill. I also knew it was southerly. But at this gate there was a sign for the Pennine Way and it was not going south, but there were flagstones and it was the only path amongst bog and bracken. I still didn’t think I’d gone wrong, and when I looked behind me, the OS maps man was following so I must be right, right?

At the other side of the bog, I joined a track and then to my right, nearly a dozen runners arrived, and I’d never seen them before. I had been running with two other people in sight, mostly, for miles, and suddenly there was a crowd. Oh.

I thought: I’ve obviously gone wrong. I thought, I wonder how much I’ve short-cut. I thought: But as long as I dib at all the checkpoints, I can’t be disqualified. There was no way I was running all the way back to the missed turn-off, nor making my way through sodden bogs to get onto the correct route. I kept on.

It was nice to have different faces around, although I couldn’t work out whether they were walkers or runners,as not that many people were running by that point and on this terrain, which was vigour-draining bogginess. It’s hardly polite to ask someone if they’re walking when they’re supposed to be running. Sometimes I thought I knew what was what by people’s footwear, until someone in what I thought was a pair of hiking boots starting running, and I gave up. By now I was in the minority for having kept my Santa hat on, so I was pleased to be Santa-ed into second place by this man:

I headed upwards, but mostly following people and thinking I’d never have found this on my own. I was still running and feeling a bit stronger. By now I was near a group of young women who I’d only encountered after my accidental short-cut. Even without the shortcut I wouldn’t have thought we’d be anywhere near each other in the race field, but I looked later and learned they had been Early Starters. I can’t remember the next stretch: it seemed long and all I knew was that it ended up in Mytholmroyd and that Mytholmroyd was the last step before Hebden Bridge golf club and warmth and food.

I crossed over Burnley Road again, puzzling Christmas shoppers with my mud and Santa hat, and I was in the last mile.

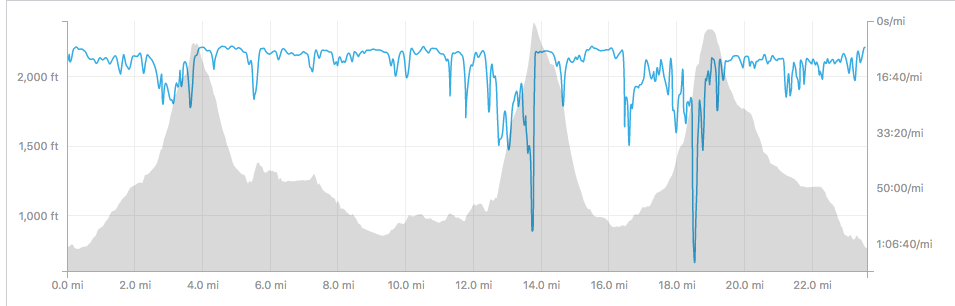

It was a nasty mile. I don’t mind testing finishes. I’m quite fond of Butt Lane on the Yorkshireman, or running up cobbles, or any uphill finish. I’d rather have an uphill finish than run a lap around a field. This though: we were at the bottom of the valley and had to climb to its top and the Calder Valley is properly steep. It was only slightly shorter than the steepest climb: 700 feet after 20 miles. Also it was exactly the route I’d done 7 days earlier only I’d been careering downhill, not slowly trudging upwards dreaming of pie.

It was hard. No-one was running by now, and there was general trudging and silence. I felt exhausted, both my knees hurt and I was in a world of niggles. Up, up, up and more bloody up, till a footpath that veered off the road and was a shorter way back to the clubhouse. Then the tarmac drive that also headed uphill.

Make it stop.

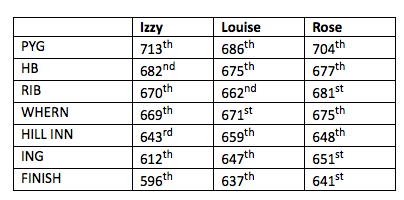

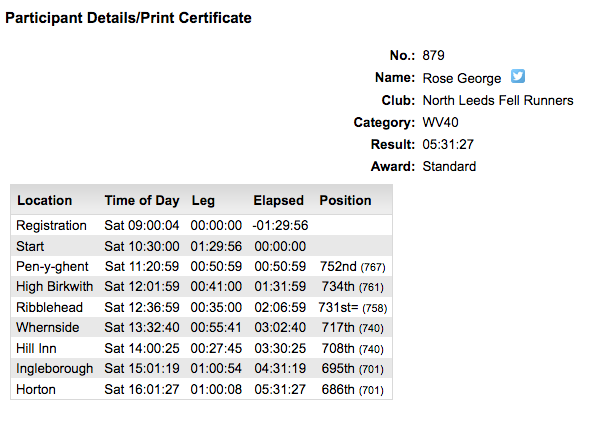

It stopped. I finished. 5.09. Inside, I found Tanya, who had only come in 15 minutes before me, and had found it oddly tough. It was harder than Tour of Pendle, she said, although it was less climb but more distance (5000 feet over 17 miles, 3500 feet over 21 miles). She’d gone wrong a few times, missing High Brown Knoll trig so that she passed under it hearing Dave Woodhead’s voice through the clag. I’d got half a mile less on my watch than she had.

I got my cheese and potato pie and when the server said “do you want mushy peas with that” I practically yelled OF COURSE I DO. Hot pie, mince pie, still not enough liquid. The walk back to the car, in the delayed heavy rain that was now falling, seemed a very very long way.

I was 9th V50 woman, which is a fact that I find delightful: that so many women over 50 are so strong and fabulous that I haven’t a hope of winning category prizes except in tiny races. I didn’t get a prize for wearing my Santa hat all the way round, but I did get a packet of miniature Cadbury chocolate bits and bobs from the bran tub. Everyone’s a winner.

It was a grand day out. I’d got to unknowingly run through and near places called Cock Hill, Miller’s Grave, Bogs Eggs Edge, the famed Tom Tittiman, Cludders Stack, The Notch, Egypt and of course Horodiddle.

All that, all those moors, and all that sky, with a pie to finish, for £15.