DNF.

Did.

Not.

Finish.

My first ever. Entirely avoidable. And entirely my fault.

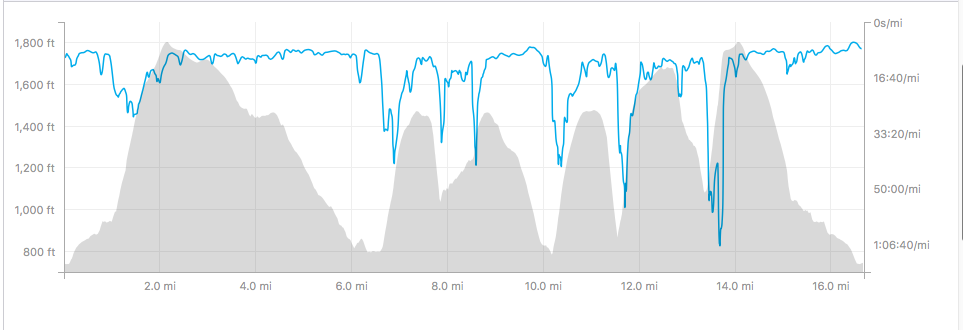

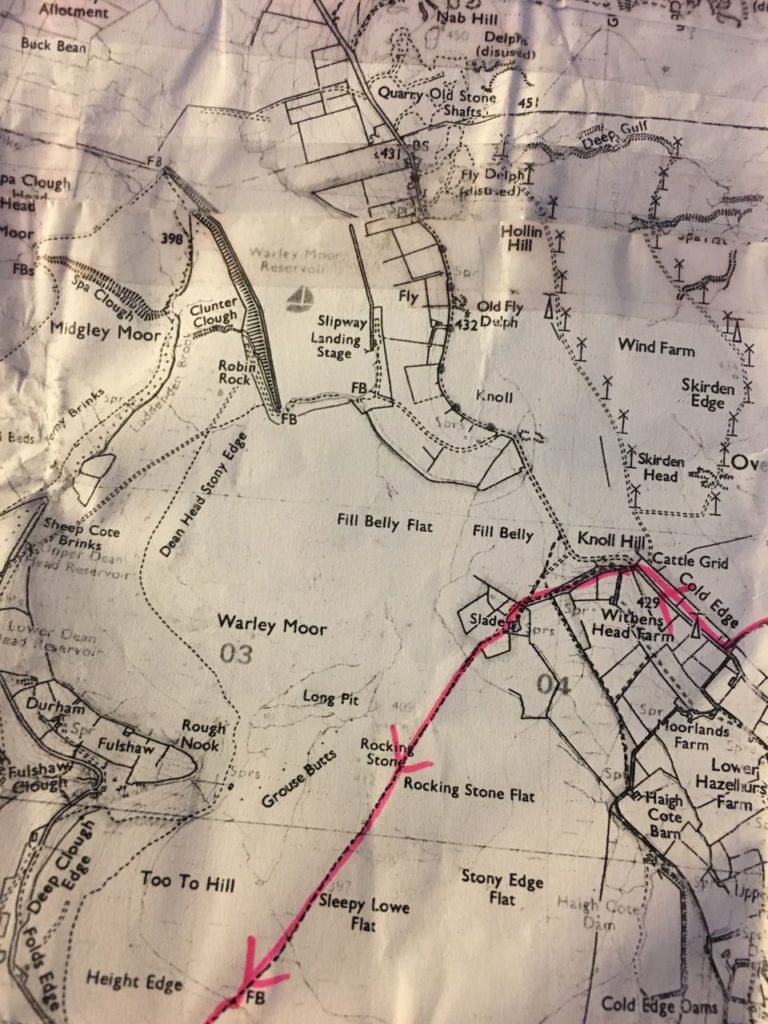

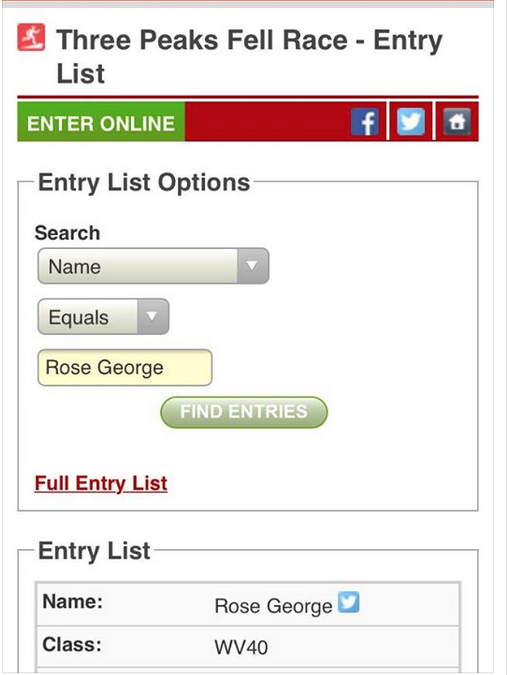

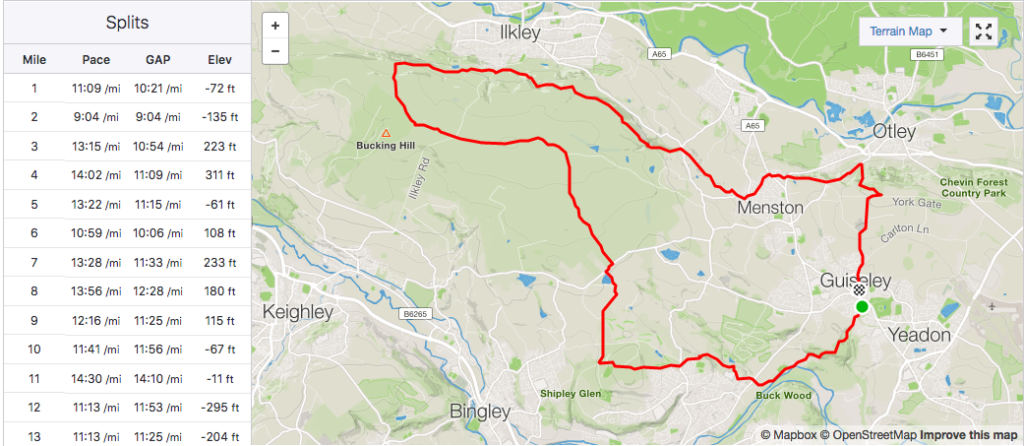

Heptonstall. I ran this last year and all I remember of it was pouring rain from start to finish. It was meant to be held last Sunday but was snowed off. I couldn’t have run it then as I was still deep in book editing. So I was delighted when it was rescheduled for this Sunday and I was even more delighted when the weather forecast promised warmth, dryness and sunshine. It delivered on all of those. For the past two nights, I’ve had Heptonstall stress dreams. I can’t remember the details, but both times I was impeded from getting to the race start. The second night, I started but ages behind and by the time I woke up had not caught up. I suppose I had reason to be nervous: I’ve only just finished an intense several weeks of 12 hour days. I have kept fit, but not kept to my 3P training plan, and not done as many long runs as I was meant to. I ran out and did ten miles as soon as I could, but even so, I know my fitness is not what it should be by now. I remembered Heptonstall was hard, principally because my Strava description of it was Oh. My. God. And I knew there were cut-offs. I checked them, and I checked last year’s time, and it seemed like I’d easily meet them. FRB advised me not to worry about them so I didn’t. I worried so little about the race that I didn’t study the route. I didn’t have time to recce, and the rescheduled race was only announced late last week, but I could have had a good look at a map. Remember this bit.

We got to Heptonstall in good time. The roads were clear, the sun was shining, and the Calder Valley looked as magnificent as ever. We parked and walked down the cobbles to the start in the pub. When I say “in good time” I mean this early.

But by the time I had got my number and my free SIS gel – “Apple? Lime and lemon? Chocolate?” – the man at the museum who gave us tea last year would have opened up and would hopefully be providing hot tea this year too. He was. His name is Rupert and he is a very nice fellow. We went over and had tea and learned about his willow plantation and how he wants a coppice to do coppicing for basketry, and that it’s too cold in Heptonstall to stay there sometimes, and that even last week, when the snow wasn’t so deep but the drifts were mighty, people still came to the museum, and he still opened up because the council pays him for 10 hours a week and so opening the museum is, he feels, a duty. Our mates Louise and Chris from Kirkstall arrived, and eventually we all made our way back up the cobbles to change. I made the vital – and correct – decision to go vest-only. The first of the season. And I was never cold. I was many things during this race, but not cold.

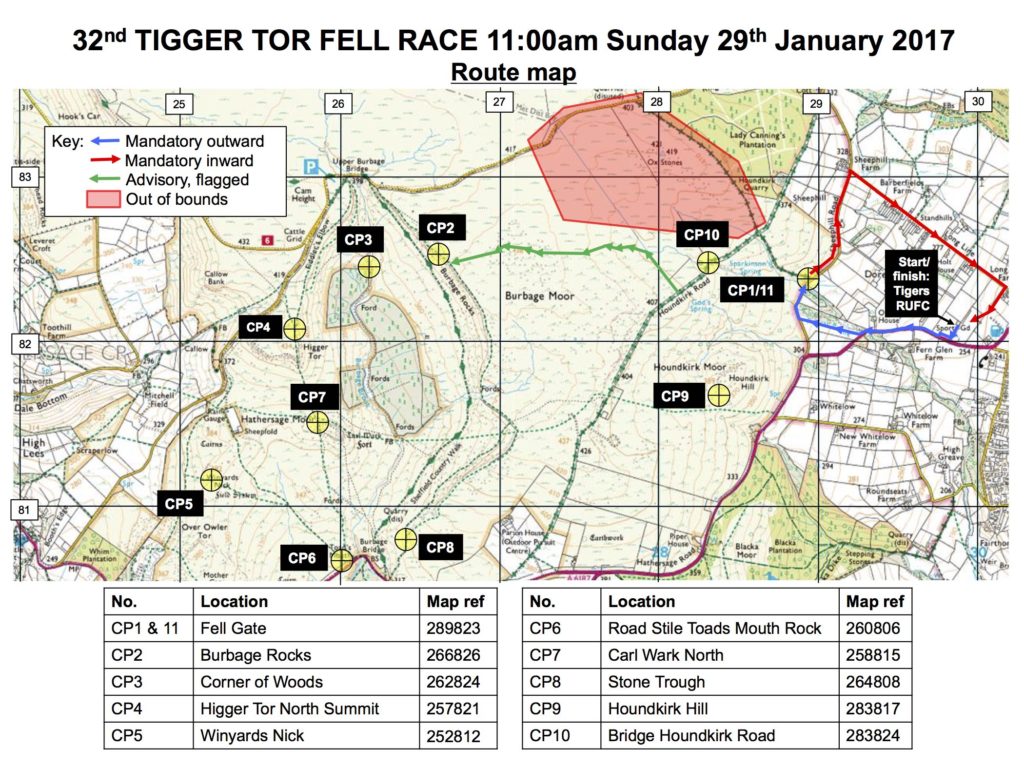

Back to the pub, a quick warm-up, then words from Steve the race organizer, who told us about two, no three hazards, then described where they were using place names only locals or people who had studied the route would know. Oh well. I suppose I’d recognise a steep drop and a massive bog when I got to it.

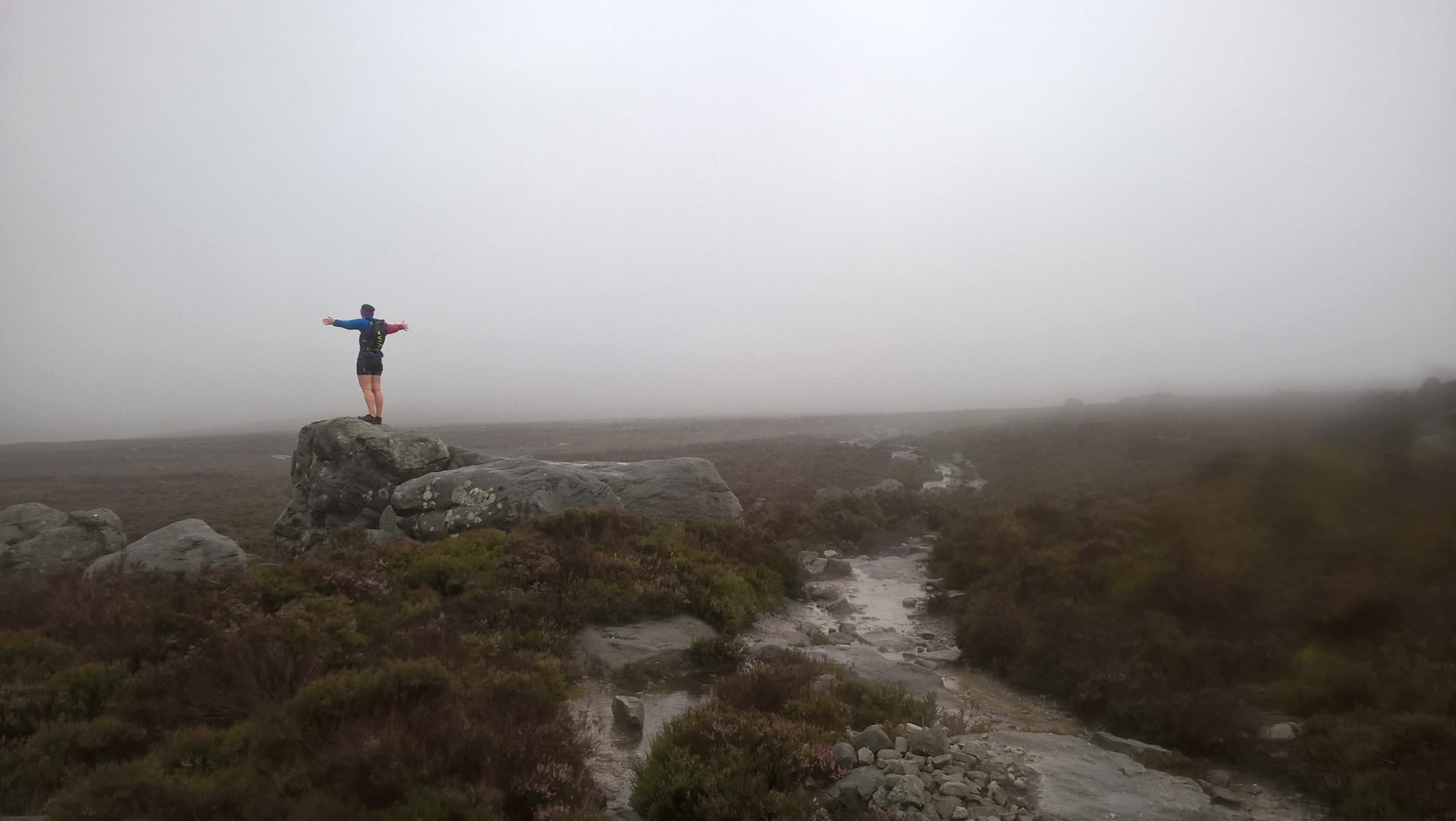

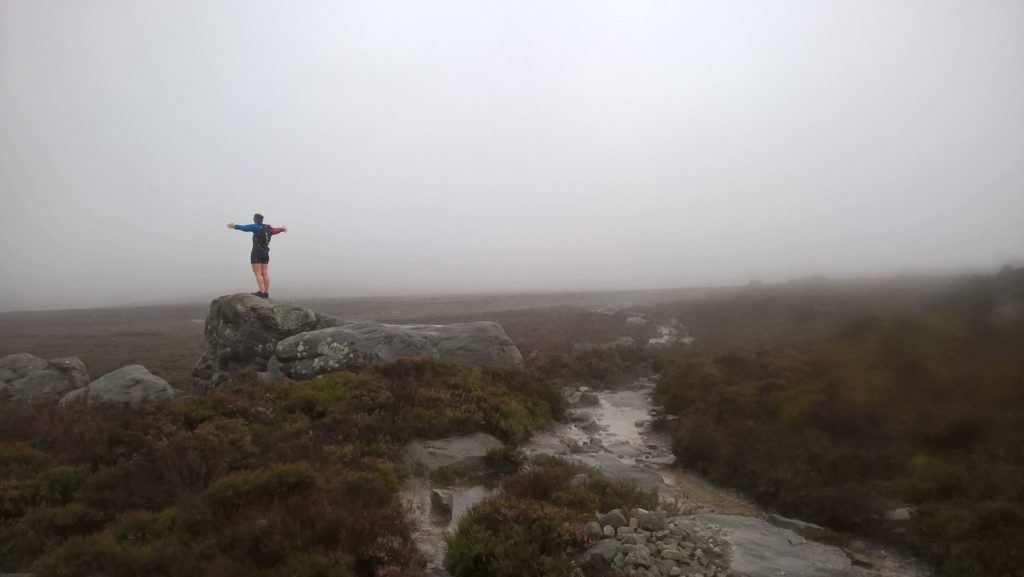

Usually the race is started by Howard the vicar, but he must have been elsewhere in his parish so a hoot and we were off. Up the cobbles, then further up. I felt OK and then I did not feel OK. Oh dear. This may be harder than I thought. But at the point of me feeling like I would not make it to mile 2, there was a lovely descent and of course then I thought I’d easily run the 15 miles, conquer the Three Peaks and basically be invincible. Until the next uphill. After that I don’t remember much until the long stretch of moor between CP1 and CP2. It will be soggy underfoot with the snow melt, said FRB, and he was right. Ouf, it was sapping. But I plodded on, trying not to think of cut-offs, and all was well. There was a tremendous downhill on soft ground with no hidden hazards. This is the absolute best kind of descent. Halfway down there was Eileen of Woodentops which made it even better because she always greets me with an Eyup! How are you? and it is always a pleasure to see and hear her. I remember thinking just after I’d passed Eileen, as I was hurtling downhill in glorious sunshine with views that people pay to see, that it was joyous. I was full of joy. All was well.

On then, to the big bog, which I remembered as soon as I got to it, and managed to remember also what Steve had said, which was not to climb the wall, please but to pass to the far side. There were little red flags pretty frequently placed. This was useful because the race field was only 160 which meant that a) I could easily come last and b) I would probably be running in a very sparse field. For a long time I ran alongside and nearby two men, a short Clayton-le-Moors man who powered uphill impressively, and another man with whom I pendulumed. At one point, he went off a track up a hill, but there were no flags visible and it felt wrong, so having followed him, I turned back and found the right route and felt proud of myself. Remember this bit.

CP3 was manned by three very cheery Scouts. At that point, I thought of cut-offs again as I knew that the first was at CP4 and the second at CP5. The trouble is, I couldn’t remember what they were. I convinced myself that the first was 1 hour 45 minutes, and with this in my mind, I tried to get a shift on, and was so focused on a long downhill to the farm where I was convinced CP4 was, I missed the turnoff and was only turned back by a Calder Valley Mountain Rescue man yelling at me from the other side of the wall. NOOOO! BAAAAACK! Thank you, Calder Valley Off-track-Runner Rescue.

I’d run for about 1 hour 40 by then, and the CP was not at the farm so I decided he had said not 1 hour 45 but that we needed to be at CP4 by 12.45, ie a duration of 2 hours 15. But that was making my head hurt and by now I was feeling very depleted. I ran across the reservoir, one of the few parts I remembered from last year, but only because the year before, I had stood there handing out sweets to runners. At this point I definitely needed something and ingested a shed-load of sugar: two jelly-beans, then a gel, then some flat Coke. It worked and I felt a lot better. I tried to get a shift on, and remember there was a descent on a very soft path through woods, then at some point two marshals standing on a bridge. CP4 and I had made it with ten minutes to spare. Great. I headed past them, and turned left into the woods, then kept going. And I kept going. And I kept going. It began to feel wrong. Slowly, I realised I hadn’t seen a flag for a long while. I realised that there were fewer studmarks on the ground. This should never be an indication of a true path, as I learned when some friends followed studmarks up Pendle Hill and did two extra miles. I asked a few walkers, have you seen runners, and they all said yes. I asked, did they seem lost? And they said, no. So I kept going until I came to a weir and a mill-house and found the Clayton-le-Moors man standing there looking as lost as I now felt.

A slow panic. A mild dread.

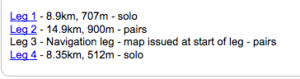

I got my race map out. I decided we had gone too far along the river, but then I made a stupid error. I thought we needed to stay on this side of the river. I can’t explain why I thought that except it was a thought that had taken root in my head, based on nothing. Let’s climb up to the top and see, I said. And I believed that there had been a switchback leading up the hill we were now climbing, and that we had both missed a flag, and that we would reach the race route by walking along the ridge of the hill. That sounds easy, doesn’t it, walking along a ridge of a hill. It wasn’t easy. It was a steep scramble, then there was no path, the ground was soft, there were branches and roots and logs and a camber so severe, the sides of my feet are now bruised. But I thought this was right and I soon learned my fellow Lost-mate was as navigationally clueless as I was. Eventually, I realised I must be wrong. We should descend to the path along the river then head back to CP4 and ask for help.

We did this, but at that point being lost was giving me stress-brain that was making clarity of thought and decision-making even worse. My Lost-mate was no better, and I’m convinced that if either of us had got lost on our own, we’d have somehow figured it out. But it was a perfect storm of increasing dithering and confusion. On the river path, we headed back to where I thought CP4 was, on a bridge. We got to the bridge I thought it was, and there was no-one there. We’d probably spent 40 minutes or so trudging along the hell-ridge, and I would definitely have been towards the back end of the field, so it was entirely possible that the marshals had packed up and gone. But then I was suddenly unsure whether it was the right bridge. And the more I thought about it, the more I realised that I had no clue about anything any more, an and no idea how to get out of this fix. I got out my map and this time my compass, and I figured out north and south and which direction we needed to be heading, but then I still couldn’t understand which side of the river we needed to climb up. I can’t explain that now because it’s actually very clear. But I was stressed and despondent and panicking, and I still thought we needed to be on the eastern side of the river although the map told me something different. Partly it was because from the east I could see no path along the west. I couldn’t see a way out. Finally I understood we were probably on the wrong side of the river so we crossed it and found a track heading south along the eastern side of the river. We set off, and if we had carried on running, we’d have seen a flag, because the race route passed over the track. In fact, after the bridge with the marshals, there was only 50 metres or so on that side of the river before the race route crossed over the river again over a bridge and headed up the hill. We were a couple of hundred metres away from the race route.

But this didn’t happen. We never saw the red flag because a man in a Landrover was driving down the track and we asked him for help. He was from Midgeley but was looking after the poultry for his farmer friend nearby. One has disappeared, he said. Fox. Feathers. So he didn’t know where Turn Hill was – the location of CP5 – and he didn’t know how best to get to Heptonstall. He suggested we drive down into Hebden Bridge and make our way from there, but although I could not manage to make my way from CP4 to CP5, I did know that Heptonstall is a heck of a climb above Hebden and I wasn’t planning on doing that. By now I knew my race was over. Even if we found CP5, we were way outside the cut-offs. I should have been upset, I suppose. I’d never DNF-ed before. DNF. Did. Not. Finish. But I was in such a state of bewilderment by then, I didn’t really think about it. The Landrover man suggested that he dropped us at Gibson Mill, the mill I’d seen by the weir where I’d encountered Lost-mate. There were National Trust people there, he said, and if they didn’t know the race route, they would know how to get to Heptonstall by footpath. He dropped us there, very kindly, and the National Trust man, very kindly, let me use his phone to call the marshal number on my race-map. I was anxious that we had both gone missing and that people would be waiting for us for a very long time at CP5. In his pre-race announcements, Steve had emphasized that anyone who retires must make that known to a marshal. I knew this and that this is what I should have done. But I still had no clue where CP5 was. The phone number went to the voicemail of “Derek in Informatics” which didn’t seem right. Then I remembered that I was using last year’s map and the number was probably wrong.

Lost-mate and I agreed that at this point, the best thing to do was to get back to Heptonstall as quickly as possible. The nice man from National Trust gave us clear indications: up here, footpath through the woods, a switchback, go straight over, ignore the track, look for Slack Methodist church then run along the road. But I hardly took any of that in and neither did Lost-mate. Instead we ran along the path, with legs that now felt rather battered, until I saw some buildings and something that might have been a Methodist chapel. I asked some walkers again, because I hadn’t learned my lesson, and they said, dunno. I asked another one and he said, go up this path and Heptonstall’s right there, as if we were very peculiar for not knowing that. We got up the path, found Slack, turned left along the road, then up the road to Heptonstall. A few people told us “well done” as we passed, which was odd. We weren’t on the race route. I saw my friend Ben at his car and he shouted WELL DONE ROSE and I shouted back WE GOT LOST. It was strange that the closer I got to the finish, the more upset I was getting. I felt stupid and angry with myself.

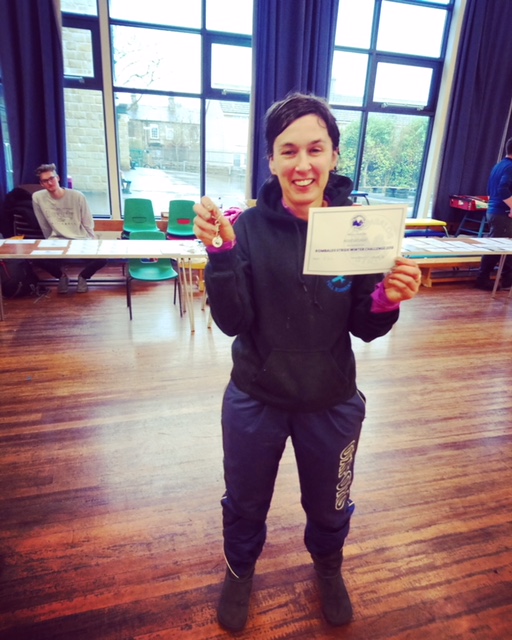

Onwards, down the cobbles, a left turn that led to a track on a wall on the other side of the race finish. FRB was there and saw me and immediately looked concerned. God knows what I looked like. Terrifying, probably. At that point all the stress of the previous hour was funnelling into a powerful need to weep in shame and frustation. This was daft. I hadn’t been injured. I’d had half a race and loved it. All I’d done was get lost, about a mile and a half from the race finish. We went inside the tent where Heptonstall’s famous flapjack is served, and I reported in to the radio operator there, who groaned and said, “YOU’RE number 4.” Then I went outside to report to the finish marshals, and I was profoundly apologetic. A very lovely woman said, no, we were just very concerned, but we knew you were probably together as you were both missing, and we’re just glad you’re not injured.

I got back to FRB and other friends, and they suggested flapjack but I didn’t have the stomach for it. By now the adrenaline of being lost and unable to understand why had changed into deep embarrassment. No matter how many people said, “it happens,” which I know is true, this was the first time it has ever happened to me. I’ve been worried many many times on races about getting lost because of where I generally am in the field, but I have only got lost twice before, one mildly and it was quickly resolved, and the second time at the British Fell Relays, which was not. This was worse though. Lots of people had got lost, my friends said, and most of them at the same point as I had. Most, though, ran on and then turned back and found the route, or got to the mill and found the track and made their way back that way.

I got changed and headed back to the pub for cold soup. If I want warm soup, I should run quicker. After the presentations I apologised to Steve, the run director, that I had caused anyone any concern. He said it was fine, and that the marshals at CP4 would usually have been standing at the bridge that led back over the river, and that’s why it wasn’t flagged. But they had chosen to stand on another bridge, and so people had missed the turning. But he said, we’re just glad you’re alright, and because of the weather we weren’t too worried.

Next time, said FRB, get into a habit of looking at your map at each checkpoint and understanding where you are. Do you do that, I said? “No. But I’m different.” This is true. He is navigationally competent. How ironic, that I was meant to do the FRA navigation course in March but had to cancel because of my book.

I’m fine now. It happens. It happened to me. And these are the reasons it happened:

1. The field was sparser than expected because it had been rescheduled

2. The marshals were on the wrong bridge

3. I had last year’s map with the wrong marshal contact on it

4. I had no phone. (This was irrelevant as there was no signal in the valley but might have come in handy when we got higher up and I could have phoned FRB to ask him to tell the race organizers we were safe. Then I would not have run for a few miles intensely worried that everyone would think we were missing or injured.)

5. My map was not detailed enough to show bridges, and because the race route had been traced in yellow, it obscured details. That’s my excuse.

These are all reasons. But it was entirely my fault that I got lost. Because:

1. I didn’t have time to recce

2. I didn’t study the route because I made assumptions that it would be flagged throughout and that I would have people to follow. I should not rely on flags, and there is no obligation on fell race organizers to flag at all. So this was foolhardy of me

3. I did not get a grip of my confusion and just got in more of a state

4. I didn’t have an OS map with better detail

I have learned my lessons. Be better prepared. Never assume a race will be flagged. Never believe walkers who tell you they have seen lots of runners (though so many apparently got lost, perhaps this was true). Always believe there is some truth to your stress dreams, even if they get wrong which part of the race you will miss.

It hasn’t been my best racing day, but of all the days to get thoroughly lost, at least I chose one with glorious weather. Heptonstall is a fantastic race and I will be back next year and I might even finish this time. Also, I never got my flapjack.

x

x