Or, how to turn a trail race into a fell race, without meaning to.

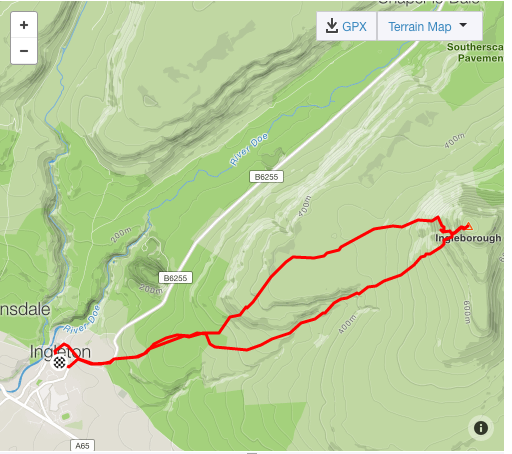

It’s gala season. Gala races are fun, because they are often short, there is often ice-cream afterwards and before the race starts you can watch 11-year-olds put their all into winning sack races. On Saturday it was Ingleton Gala, and Ingleton Gala Mountain Race. Fell-runners can often argue about whether a fell race is clearly a fell race. Plenty of people think the Three Peaks is not a fell race and that there is very little that is “felly” (yes, that is a word and if not it is now) about it, as most is on clear paths and there is a lot of hard surface as well as three mountains. Ingleton Gala Mountain Race was definitely a race, and it definitely involved a mountain, as the race route consisted of heading up to Ingleborough, known by me as the “one I always mean to run to but always walk to” as it’s the third of the Three Peaks and the only one beyond the Hill Inn cut-off. It is also known by many as Inglebugger, either because it is the third peak of three, or because of its severe and steep face of limestone rock. But most of the route is on a well-defined track, so it’s probably a trail race.

FRB has been ill and injured for the last month: first he was injured, and then he was ill. But he is feeling better on both counts and decided to come up for the day and support, so off we set on the usual route to Skipton, then to Ingleton. It was a civilized race start of 3pm, and we got there with time to spare to check out the gala. £2 entry to the gala and £4 for the race. The checking-out of the gala didn’t take long: there were sack races and obstacle courses, a few stalls, and some magnificent raptors who, as I wasn’t feeling full of vim and vigour, I thought of asking for a lift up the mountain. The weather was good: not too hot or muggy, and overcast, though warm. I saw a few runners with what looked like full kit back packs, but there were no signs one way or the other, so I asked at registration. Yes, they said. Full kit. I must have looked surprised: many gala races in fine weather relax kit requirements. It wasn’t that I disapproved: I usually find more to disapprove in macho runners who refuse to carry water or any kit, as if they will magically sprout feathers or fur and a water fountain if they break a limb on the tops. The man at registration said, “full kit because someone broke his leg last year and he got cold very quickly.”

I said, “Right. Yes. I approve.”

Pause.

“Not of the broken leg, obviously.”

I fetched my kit. The only thing that was sub-standard was my race map: I’d forgotten the OS map on my coffee table, so I had the Three Peaks map, which had half the race route on it. It wasn’t ideal, and I was annoyed with myself that I didn’t have the actual race route, but I didn’t think I’d need it. There were no kit checks, and we gathered in the sack-racing field and waited. Then we waited a bit more. The announcer said, sorry, he needed to find Paul the ambulance man, as he had a call-out. Behind him was a fire engine and crew who were doing a show-and-tell-and-climb-over-our-fire-engine session at the gala. Suddenly the crew all climbed into the truck and off they went too. (It was because of this head-on collision.) Finally there was a brief count-down and off we went. I had no tactics in mind other than getting up the mountain and getting down again. I felt OK: not too hot, quite sprightly. I ran more than I thought I would, keeping an eye out for FRB. He finally appeared after about two miles, though his voice appeared first, as it was shouting “ROSE YOU’VE GOT TO RUN NOW.” So I did. I passed two people in front of me and said, “I’m only running for the camera” and they laughed and FRB got this lovely shot:

Up and up we went, and the overcast became clag. I can’t ever remember seeing Ingleborough in fine weather, though FRB says we did once, on a recce. Today it looked first like this:

And then like this:

That shouldn’t have been a problem. This was an out-and-back race. The most straightforward kind: you go up on one path, and you turn round at the trig, and you come back down on the same path.

As we neared the final climb to the summit, the leaders began to come back down. They were pelting, zooming, whooshing past us. As I plodded up and wondered when the hell the summit was ever going to appear, I thought: that looks like such fun. I began to look forward to the descent. A woman next to me from Saddleworth was saying “well done” to every runner who passed her. I thought this was a) extremely generous and nice and b) a waste of breath she needed to get up the mountain. I usually say well done to the top three, who are always going too fast to say anything back; to people I know; and to the first couple of women. The Saddleworth woman and I had a chat, and she expressed some concern about how rocky the path was and that the descent looked really tricky and technical. I stupidly mentioned that someone had broken his leg the year before, and immediately wished I hadn’t. Sorry, Saddleworth woman; that was not diplomatic of me. Still, feeling guilty about that kept my mind off climbing for the next five minutes. I didn’t share her worries: I was dying to get to the top and then do some hurtling. Where I fit in the race field, I am improbably fast at descending, because I love it. A lot of folk of my pace are more cautious. So I can usually take several places, which I usually promptly lose on the next climb. All this was in my mind as I kept going up — helped by a big fellow with a beard who did a good “whoop” now and then — and finally there didn’t seem to be any more false summits, just the faint outline of a trig point, around which we went anti-clockwise then headed back to the path. I’d seen runners coming down from the summit way off to my right, and earlier, a lot of the fast runners had come down off-piste. Both these things were in my mind and in hindsight I wish they hadn’t been.

I started on the path. I overtook people who had been running around me. And then I veered off the path in search of better ground, and I veered too much. I don’t exactly know what happened for the next five minutes, but suddenly I found myself unable to see anyone or hear anyone, and there was nothing but profound clag all around me. I knew I was on Ingleborough, and that there were villages within a few miles, but suddenly it seemed such an unearthly place. So quiet and desolate. I began to panic. I realised I hadn’t been concentrating on anything but my feet, as I was so giddy to get on with the descent, and now I had no idea where I was. For a while, I heard faint voices, but I think they were on the summit. I shouted several times and no-one replied. Then I really began to panic. Luckily I had my phone, and I knew FRB was on the track a couple of miles below. Also, very luckily, I had reception. I phoned him. The phone was answered but there was silence.

Me: Hello?

FRB: Well done Graham

Me: HELLO?

FRB: Well done Chris

Me: FRB?

Me: FRB ANSWER THE PHONE?

Finally he said hello. He’d been cheering runners going past. Later he told me that I’d pocket-phoned him while I’d been running up (I’d done the same to my mother who later said, “I don’t know if it was a mistake or whether you actually wanted me to hear the sound of your footsteps”). All he could hear that time was breathing and thudding. This time I was breathing heavily from running downhill and from anxiety, and so FRB thought I had done the same thing.

Me: I’m lost.

There was a pause. I’m quite certain that in that pause FRB’s brain was trying to calculate the chances of someone getting lost on a race route that consisted of going up a path and down the same path. Then he recalculated, adding in the fact that it was me. But he was careful to sound kind.

FRB: Where are you?

Me: I don’t know.

FRB: What can you see?

Me: Sheep. And clag.

I carried on describing what I could see, babbling, until he said ROSE BE QUIET.

For some reason I didn’t think to get out my compass at this point and for some reason FRB didn’t think to tell me to get out my compass. If I had, I’d have known from the map to head south-southwest. Instead, FRB said, can you see some conifers and a farm? Yes! (Later we realised we’d been talking about different conifers and a different farm). He said, can you see the sun? Sort of.

OK, he said, head for the sun. That’s pretty much the right direction. Call me in ten minutes.

I obeyed. I ran, I walked. I still couldn’t understand why I couldn’t see a path or any humans anywhere. It was just me, wild landscape, limestone and sheep. Had I not been in a state of anxiety, it would have been a lovely trek, because it was beautiful and wild and lonely and quiet. But it was not straightforward. There were tussocks with deep channels in-between that are proper ankle-breakers. Ingleborough’s limestone plateaus have lots of holes, and I almost didn’t avoid one about ten feet deep. I stung my hands on gorse. And still there was no path. The clag had lifted, but so my perfect visibility enabled me to see that I had no idea where I was. I kept going south south-west, my compass now around my neck. I called FRB ten minutes later. No reception. This went on for about ten minutes, and I finally found some kind of trod. Maybe it’s the race route? It wasn’t. Now I can’t remember in what order these things happened, but I saw two cairns on a rise and thought they would be a useful thing to head for, so I did. I vaguely remembered seeing cairns on the way up. The trod petered out. I kept going south-south-west and came to a limestone gully. Finally I had some reception.

FRB: Can you describe where you are?

Me: I’m in a, I don’t know how to describe it. Not a valley or a plateau. A sort of sweeping thing. (Maybe the word was “cutting”.)

FRB: Okaaaaay. Keep going south-west.

I had asked him earlier to call the race director to let him know I was lost. But there was no number to call on the race number, or on the mountain race website. FRB said he had finally found it on the FRA site, but that he hadn’t called, because he knew the last runner — Antonio from Otley Runners — hadn’t gone past him yet, and until he did, I wasn’t lost.

I jumped down a short limestone drop and headed on. Finally I came to a wall, and phoned again.

FRB: I think I saw you. Can you wave?

I waved.

FRB: Hmmm. Not sure. Can you jump?

Me: Not really, I’m standing on rocks.

FRB: Can you crouch?

I crouched.

FRB: Yes! It’s you.

Now in front of me there were grazing fields and there in the distance, like the yellow brick road, shiny with promise, was the race route track. Only I was standing in front of a wall with barbed wire and no gate in sight. I asked forgiveness of the Countryside Code, checked I could only see sheep and not cows, and found a place to climb over the wall. I was careful not to dislodge anything. I ran down the next field, almost running into a dozing sheep — my version of the gala obstacle race — then over another wall (sorry, landowners), along the next field and then, oh my god, there was a field gate, and there was the track and I was back on it.

I thought I must have done many more miles, but in fact my particular race route and the actual race route weren’t that different in length. Duration though: where I reached the path, there was under a mile to the finish, and I ran down it with FRB, into the village, through the car park, down the very steep grassy bank, where I nearly took out a heedless father and toddler LOOK OUT RUNNER COMING LOOK OUT, then I sprinted to the finish. A five-year-old lad handed me two bottles of water and said very seriously how worried he was because someone had come down with a bleeding leg wound. It had taken me 1 hour and 50 minutes to run under seven miles. I assured the toddler I was fine, and then FRB and I headed straight for the ice-cream van.

At this point I was delirious with relief, which I was about to exacerbate with sugar. I was so relieved, I didn’t care that I’d come third from last, or that the woman behind me might have wondered why I suddenly appeared in front of her like a genie only one that climbs a field gate. The DOH! shame came later. We ate ice-cream, headed off to find tea, and found Randolph from Kirkstall who told me — oh marvellous Ingleton — that there were hot showers and a changing room. This, at the kinds of races I do, is five stars. I told Randolph I had got lost, and he said,

How the hell did you get lost? It’s an out-and-back?

On Instagram, I posted something about the race saying I’d got lost, and Josh, who won it, commented, “how did you get lost? It’s an out-and-back!”

On Strava, someone posted, “how did you get lost? It’s an out-and-back!”

I got lost because I got giddy and it was claggy. From Strava, I learned that I had crossed the race route, then carried on, so ended about half a mile out of my way. In those conditions, it’s not surprising that by that point when I realised things had gone wrong that I couldn’t see or hear anyone. Anyway, I got more of a fell run out of it than anyone else in the race.Nothing like making your own way between checkpoints. Via limestone gullies, hidden pot-holes, cliffs and barbed wire.

Lessons: get out the compass at the first opportunity. Pay attention. Have FRB on the other end of the phone. Do not get lost.

I know the feeling I did that last year and it was very misty and got foggier and wetter and sllippery and colder as we got up to the trig,we couldn’t see any thing I was worried about getting lost too thank fully I could just see a runner in front in the distance trying to pace my timing so I could still see them

And reception for my mobile is another tale to tell too!

There’s something about that mountain !

Well done you

Serena

Thank you: well done to you too (for not getting lost).

Brilliant article, thank you for sharing. I’m new to this fell racing and must admit, this is my fear. I’ve run faster, just to keep someone in sight, and slowed to let someone run ahead of me. Twice, and both were taped to indicate direction, but I missed it, and if I’d gone the way I assumed, it was wrong!

It was very foggy on top on Saturday, and races don’t always go to plan, but we do learn and every experience we survive is good.

Well done for finishing and not giving up.