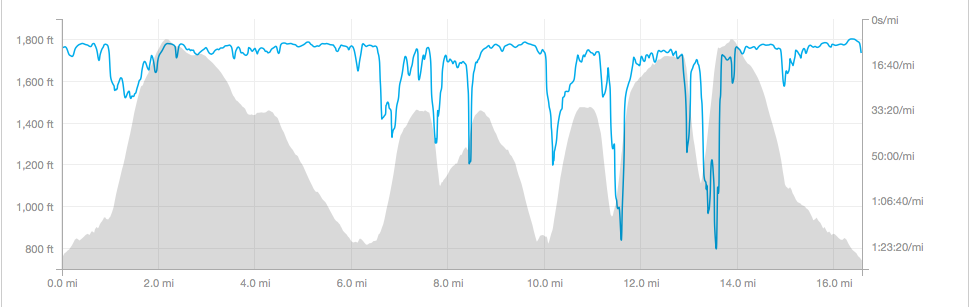

About a year ago, I was standing on the summit of Pen-y-Ghent, one of three small mountains or large hills, depending on your view, which make up the Yorkshire Three Peaks. I was marshalling the 61st Three Peaks fell race, a 24-mile run up and down all three peaks – Pen-y-Ghent, Whernside and Ingleborough – that includes 5300 feet of climb, and usually at least two of the four seasons. There were half a dozen of us marshals at the summit, and our job was to guide runners up to the dibbers, the devices that runners have to check in to at various checkpoints. The rain was horizontal. The temperature was freezing. The fog was dense. And I was as cold as I’d been for many years. As the first runners approached out of the fog, and as I jumped up and down trying and failing to find some warmth, I decided something.

Running must be more fun than freezing to your bones in a hi-vis vest. Next year, I’ll run it.

And so I have. And I got round. And I am inexpressibly delighted. Because it was the hardest race I’ve ever done, and because I nearly didn’t manage it. So here is a race report that will probably take you as long to read as it took me to get up to Pen-y-Ghent (just over 50 minutes).

Training

FRB drew me up two training plans. The first started in December and carried me through to running Rombald’s Stride in February. The second went up to last week. Each week, I had to run a combination of hills, speed intervals, tempo runs and more hills. There were negative splits, and a Chapel Allerton circuit right on my doorstep that combined a hill run, a tempo run immediately afterwards, and a recovery run. I got weirdly fond of that. The aim was not just to get me better at climbing hills, but to ensure that having climbed a tough hill, I could run off the top of it. I suppose you could call it the Running Off Tired Legs Plan.

I tried to fit in one session of strength training and one Pilates session a week. I also tried to do 100 or so deep squats a day, to strengthen my quads and ankles, both crucial for climbing, and to keep up my glute exercises which would hopefully keep my troublesome tendon happy. I sort of paid attention to my food, trying to eat lots of iron-rich kale and greens, and as race day grew closer, making sure I ate plenty of carbohydrates, and getting thoroughly sick of pasta.

Of course I didn’t do as much as I should have, either with the running or the strength sessions. Mostly that was because I was fighting depression and the menopause, or because I was taking sleeping tablets to sleep now that the menopause is messing with that too, which made me horribly dopey. But all in all, I did OK. I ran in rain and snow and wind. I ran on moors and hills and road. I grew oddly fond of Stonegate Road in Leeds, not the most picturesque of roads (anyone who has run the Leeds Half will know it well). But it’s such an elegant rise up from Meanwood to the top. I got used to training in tough conditions and keeping going. I ran up so many hills that by the end of my second training plan, I could never run just once up a hill, but always had to do it at least twice. Like Post Hill, a crazily steep climb in Pudsey, where I ran a race that included two climbs and five miles of running, and as soon as I finished, I climbed the hill again, to the bemusement of everyone. I got better at climbing hills. There’s a circuit around Harewood, a country estate just north of Leeds, that I love to do because it’s beautiful, and there are stags, and there’s a horrible short hill that is very good training. When I started the first training plan, I could never run to the top of that hill without stopping and walking. By the end of plan 2, I ran up and down it four times without stopping.

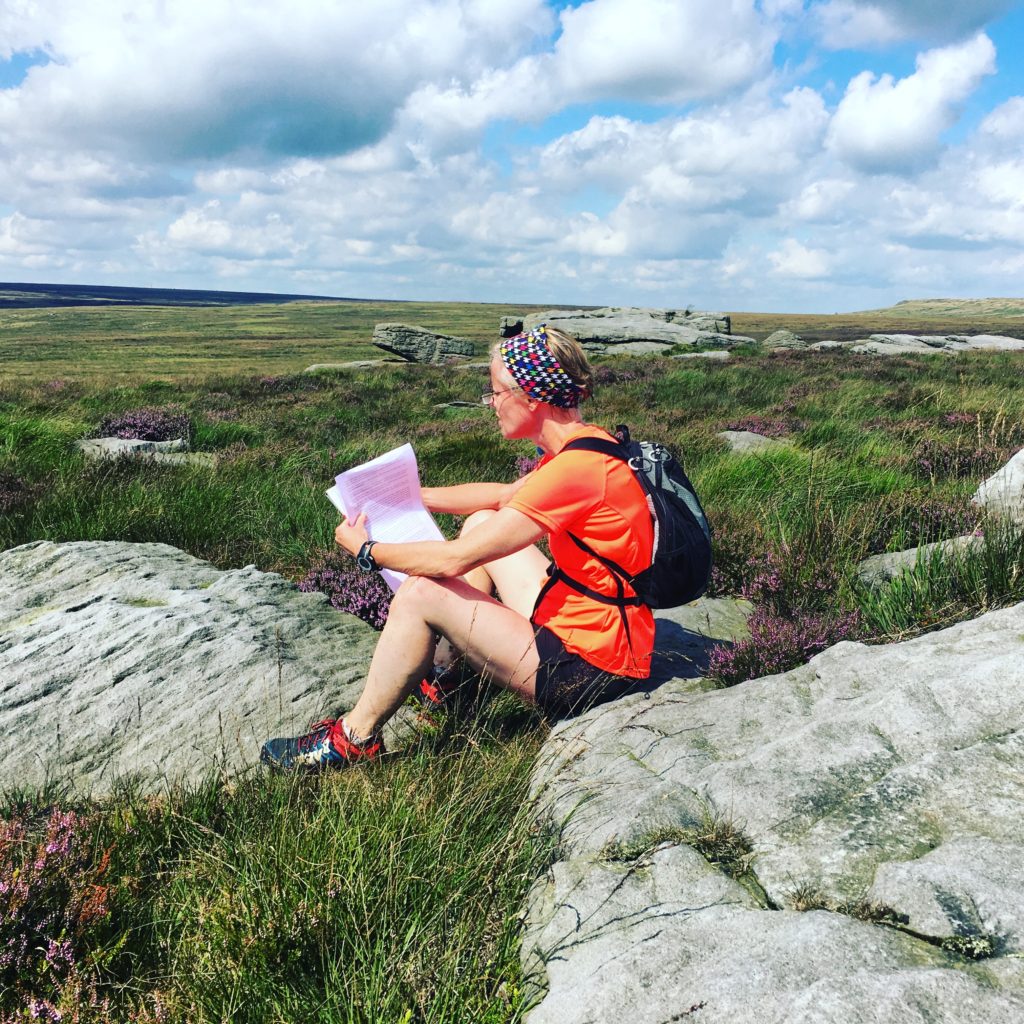

I’ve walked the Peaks, but only once, so it was important to do a recce. I also wanted to know whether I had it in me to beat the cut-offs. So I did two recces up at the Peaks, the first with FRB, when we ran up Pen-y-Ghent then Whernside one day, then on the next from Ribblehead (a mile from the foot of Whernside) up Ingleborough and the five miles back to Horton, where the race starts and finishes. It wasn’t like running the whole race, but my legs on day two were sufficiently knackered that I thought it would give me a good indication of how I might feel on race day. Then I went back when FRB was running up in Scotland and did Whernside on my own, twice, thinking that I needed to know if I could run it on tired legs. I did OK. The first time, I got to the top in 45 minutes from Ribblehead, which was far better than expected. The second time, it was slower but I would still meet the cut-offs.

Oh yes. The cut-offs.

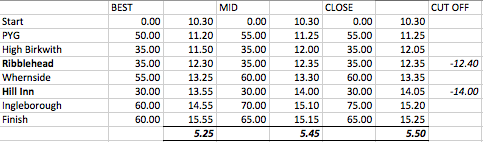

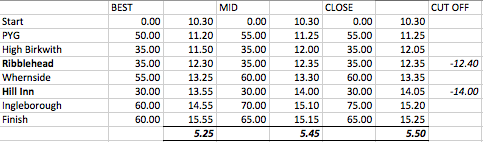

The weather of the Three Peaks can be as tough as the terrain. It can change on a ha’penny spin. And because there are dozens of marshals who have to stand out on summits and at checkpoints in all weathers, the race organisers ensure that anyone who enters is at least theoretically capable of running it in a time that will not leave marshals standing out all day. This is not a race for the relaxed. There is no winging it. To enter you must have either run the race before, or done two qualifying races of a certain distance and climb. I did Gisborough Moors and the Badger Bar Blast to qualify, and in the six months I was training, I did at least one fell race a month. On the day, you must reach each checkpoint by a certain time. If not, you will be stopped. The race would start at 10.30am and I would have to get to the checkpoints by these times:

High Birkwith: by 12.05pm

Ribblehead: by 12.30pm

Hill Inn (the final checkpoint): by 2pm

FRB had added the times I needed to run on my training plan, because he is a damn good coach (hire him!).

It’s odd though: I remember doing London and feeling streamlined and super fit. This time, although I had evidence, from every race I did, that I was stronger and better at climbing hills and even a bit faster, I didn’t feel particularly on top form. The recces had given me some confidence, but the cut-offs were still going to be tight. Right up to about 2pm on Saturday afternoon, I had no idea whether I would get through Hill Inn or not.

Friday

Both FRB and I are not particularly relaxed before races. I’m too chaotic, and FRB gets too wound up about my chaos, and the results are not relaxing for either of us. I thought that this race was so important for me that I wanted to minimise any stress, so I booked us a room at a lovely B&B in Chapel-le-Dale, the hamlet near the fateful checkpoint of Hill Inn. We had of course been checking the weather for days, and trying to ignore the freezing temperatures and snow outside. By the time we got to Chapel-le-Dale, the forecast was pretty good for race day: some sunshine, perhaps some light showers. But all the tops were covered in snow. This is what Pen-y-Ghent looked like. Inviting.

Which meant The Shoe Question.

Runners go on about shoes, but the amount that fell runners can discuss shoes makes road runners look like mutes. See, we have so much to think about, and particularly on the Three Peaks, which has track, cinder track, tarmac, bogs, rocks, rocky paths, becks, grass, and probably moon-rock too. So you have to calculate: do you want really aggressive studs on your shoes for the soft bits? But then you still have many miles to run on tarmac and hard surface, and you don’t want blisters. So do you choose trail shoes, which have less aggressive soles, but are softer on the feet? I was choosing between two shoes: Mudclaws or Roclites. Both are made by Inov-8, and both are great, but I know that Mudclaws batter my feet on hard surfaces because they have less cushioning. I decided on Roclites, which have less aggressive cleats (studs) but a bit more cushioning and would probably leave my feet in better shape.

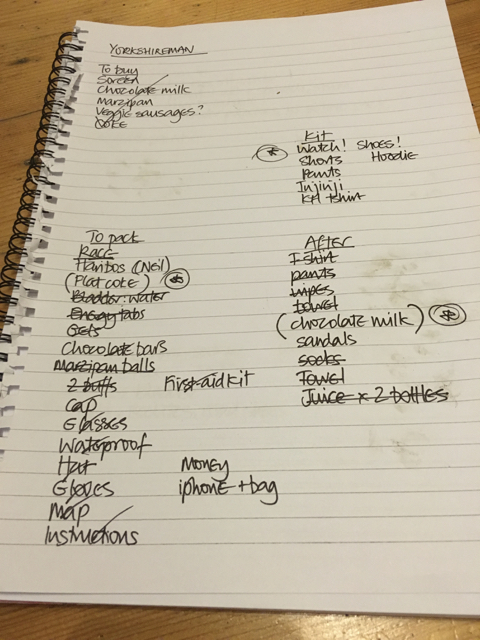

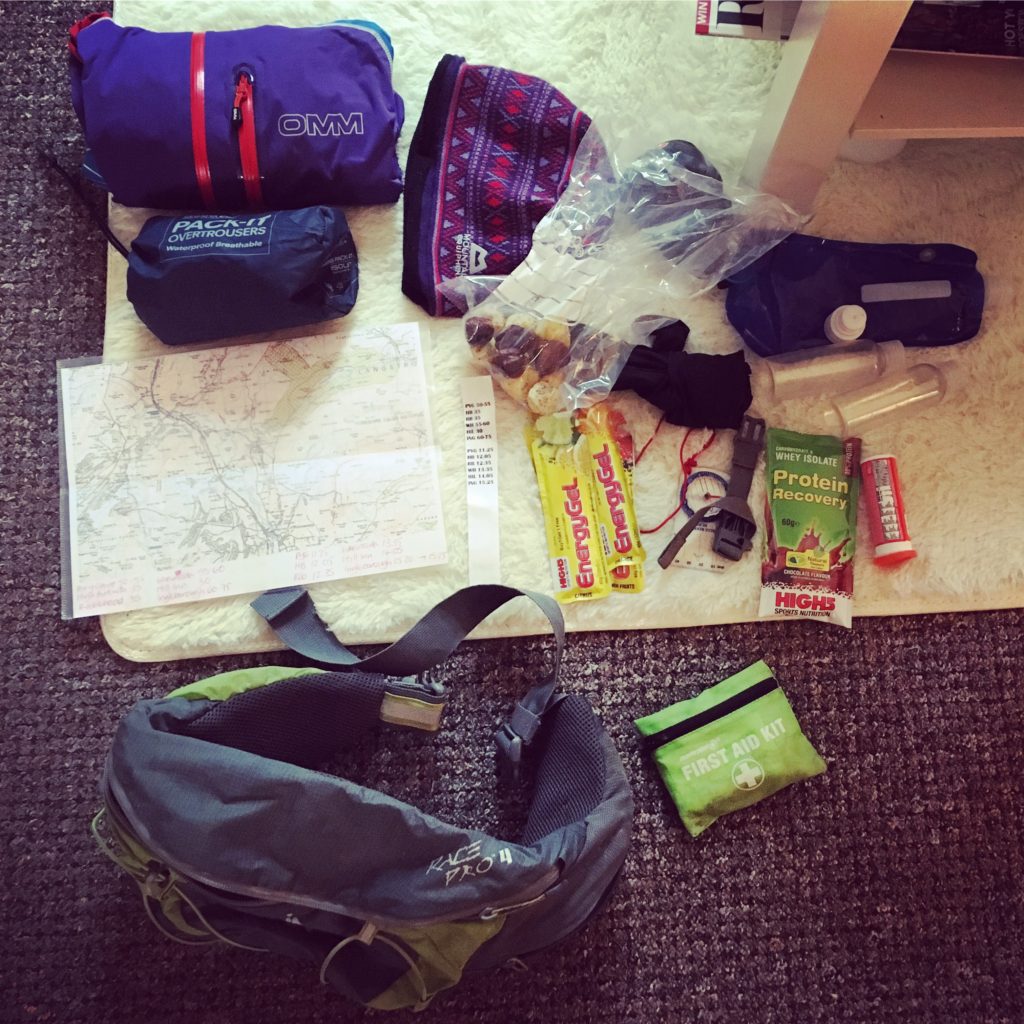

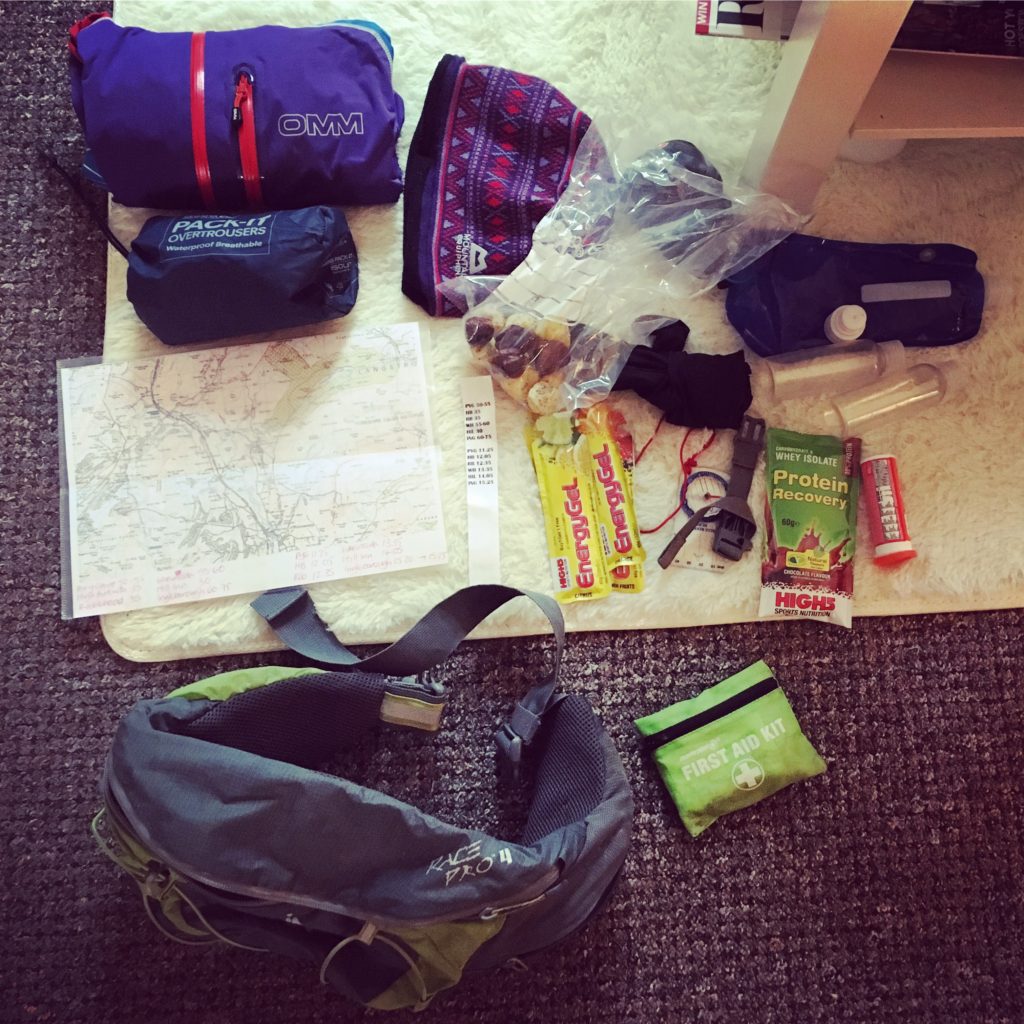

I packed my kit carefully on Thursday and packed it again on Friday. FRB’s instructions: I should make sure I knew where everything was in my waist pack, because a minute is a precious thing and I don’t want to have to stop to pile everything back in. Into my waist pack, then, went the following:

A waterproof with taped seams and a hood

Waterproof trousers

A hat

Gloves

Mittens

A compass

A whistle

1 collapsible bottle of water with electrolytes added

2 small bottles of water with electrolytes added

A small tub of anti-chafing cream

In the right pocket, solid food: half a dozen marzipan balls made with nuts and chia seeds, and a few scrunched up balls of Soreen. A Snickers bar cut in half. A bag of jelly babies.

In the left pocket: four gels

I packed another bag with warm clothing to change into after the race, plus some chocolate milk, plus more chocolate. I bought a bottle of water and a bottle of coke, and put my race number on each, because each entrant is allowed to leave a bottle at both Ribblehead and Hill Inn checkpoints. I packed ear-plugs and eye-mask in case of loud cows or sheep. And we set off to t’Dales.

But first we had to fuel up. Once again, we stopped at Billy Bob’s Diner near Bolton Abbey, on the way to Skipton, and ate everything on the menu.

Then we stopped in Settle to see a wee cycle race. I’m not convinced that cycle races are the best spectator sport, even the Tour de Yorkshire, but the atmosphere was good, and I was given some Arla protein shakes (only one at first, then I said we were running the Three Peaks. “Oh, take three then.”) And Settle was in a very good mood, which was lovely:

The tour passed, all those cyclists with their mucky faces and amazing legs, and we set off to the B&B. But first, there would be chips. We stopped at a chip shop in Ingleton, then drove out half a mile to have our chips in the car, with a view of Ingleborough, glowering, magnificent and looking very snow-bound. At the B&B, our host Martin told us that he’d had plenty of Three Peaks walkers, but that we were the first runners. He sounded like running the Three Peaks was an odd thing to do. Perhaps it is. Apart from that, we had a quiet race preparation evening in which the most exciting thing to happen was FRB asking me if I wanted to let out my gas.

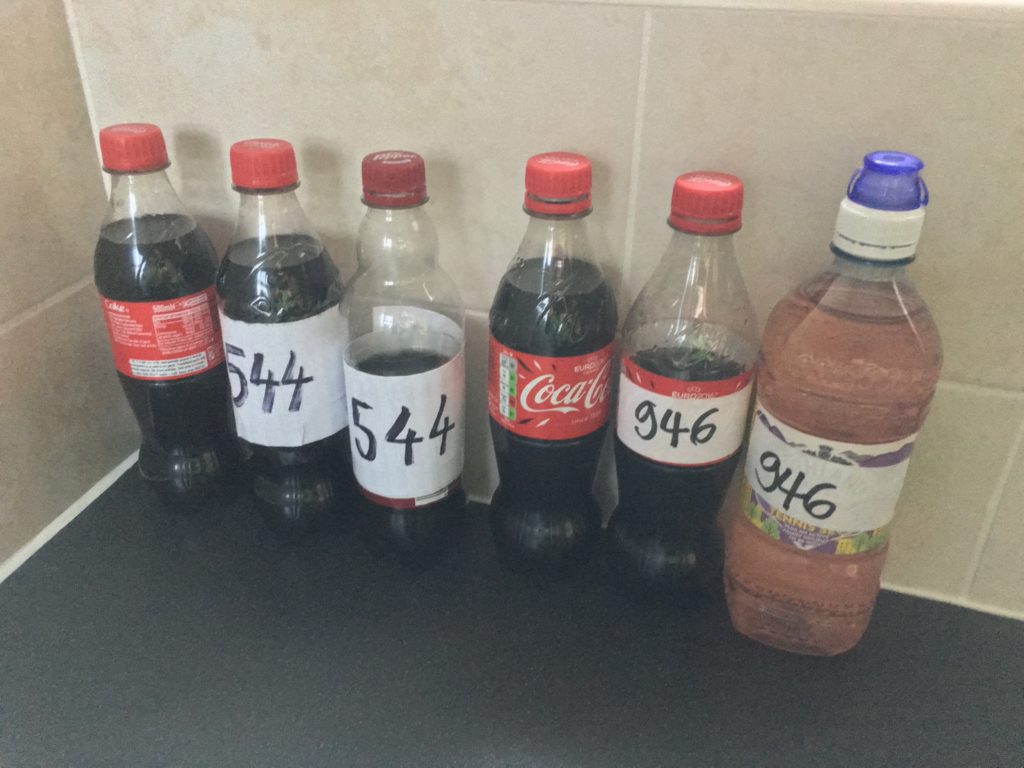

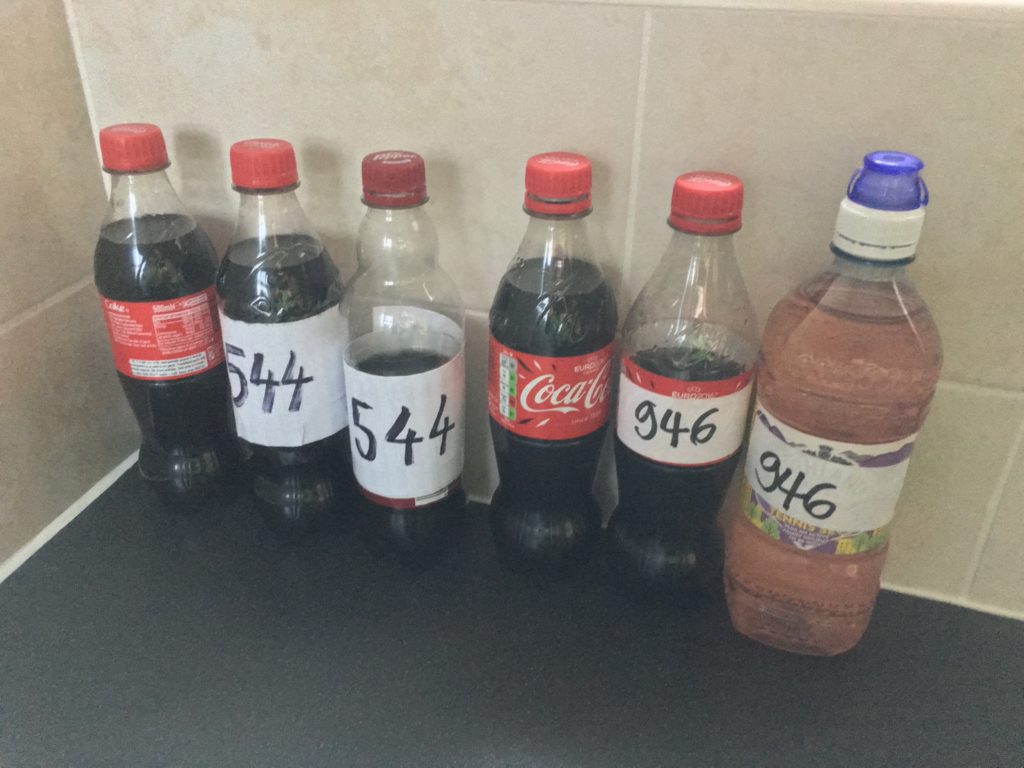

He meant making Coke flat. Both he and I were going to have a flat Coke at one checkpoint and electrolytes at the other. This is letting out gas in progress:

He also worried about where to put the packaging for the latex gloves he’d brought. Someone on FB had suggested taking some Marigolds just in case both pairs of gloves got sodden, and FRB had provided surgical gloves instead. He was worried about what Martin might think if he found an empty packet for latex gloves in the bin, though two runners about to run a fiendishly hard race are the least likely to be having kinky frolics the night before involving latex gloves. Still, we took the packaging away with us.

Then I read my friend Mary Roach’s book Grunt, about science’s efforts to make soldiers’ combat lives easier/safer/less deafening. I should have gone to sleep, but the chapters on maggots and stink bombs were way too interesting. Then, for the first time in my racing history, I slept well. Of course, I had a Three Peaks stress dream, in which Dave Woodhead of Woodentops was again a race director, and I was again late. But there were no stink bombs or maggots in it, which is a bonus.

Saturday

Pen-y-Ghent

We weren’t late. Even my chaos had been subdued by how big a thing this race was for me, and I was prepared and organised. I was surprisingly calm at breakfast, which consisted of tea and delicious pancakes with banana and honey. Perfect. We met another couple staying at the B&B, a man called Brian and his wife, who were both going to be marshalling. Then off we went to be at the race field in good time and spend about an hour and a half freaking out. Me, that is. FRB seemed calm. That’s because he knew what was coming, and because there was very little question of him not being able to meet the cut-offs, which was my biggest worry. Pen-y-Ghent was beautiful but snow-bound, and I got my number, dropped off my drinks for the checkpoints, then quietly started to panic. So I kept busy: going to get my kit, then queueing up for the portaloos. I met a woman in the queue who was philosophical: “If I get round, I get round, and if not, it’s a nice day out, so I’m not going to worry about it.” I tried to tell myself the same. Even if I didn’t get past Hill Inn, I would still have done a Two Peaks Race. But I wanted to do well. I wanted to get round. I wanted to surprise people. I wanted to beat the sodding menopause. I went to the race briefing and heard none of it, and had the first kit-check I’ve ever had at a fell race (they do happen, I just haven’t had one yet). Even so, it was bit cursory: FRA rules require waterproofs with taped seams and full waterproof trousers, but I just showed the Mountain Rescue man my pack, saying, that’s a waterproof, that’s trousers, there’s my hat. Then I went for a warm-up run around the field, and did some deep leg squats and bends, to open my hips and put less pressure on my knees. It worked, because afterwards my joints felt fine. I found a secret toilet, too. No, not a bush, but a toilet in a building at the far side of the race field. As the portaloo queue was about 60 people long (there were urinals too but men do get nervous, don’t they?), a toilet with one person waiting counted as a triumph.

I saw Ricky Lightfoot warming up too. For someone who runs on the fells so much, he looks very pale. I didn’t see Victoria Wilkinson, but I did see a few Nepalese. I thought, is a Gurkha running? But then later, running up Pen-y-Ghent, someone shouted “Well done Mira!” at a Nepalese woman descending at elite pace, and I realised it was Mira Rai, one of my running heroes.

Finally I was ready. I slathered my feet with anti-chafing cream. I had put my rainbow race socks on. I’d decided on a Helly layer under my vest, but shorts of course. Always shorts. My Roclites were going to have cope with any slush or mud. And it was time to line up at the start. I aimed for the back, so did FRB. Half of the runners were already wearing waterproofs, as rain was forecast, but I decided to wait for the water. Someone announced something, but I was too nervous to pay attention. Someone fired a gun, and off we went. Round the field, up onto the road, over two narrow winding bridges, along more road and then up onto a track that led to Pen-y-Ghent. Afterwards, FRB said, “did you see the amazing sight of all the runners in all the different colours, streaming up the road after the bridge?” No. I didn’t. I was so nervous by that point I wouldn’t have noticed a mastodon joining in. I was nervous about pacing. My pace band had times on, but actually it wasn’t a pace band because paces are pointless when you are climbing things like Pen-y-Ghent. There’s no way of knowing when you’ll have to walk, or when conditions will slow you. So I just resolved to run as best I could, and to take it steady. I was dreading the first part, as I usually really struggle in the first mile as my body adjusts – because I never warm up properly – but the warm up run and stretches had worked. The sun was shining, the fells were beautiful, and it was a lovely day to be out in the fresh air, running.

I did really well on Pen-y-Ghent, running further (that is, till the point where I started walking) than I’d done in the recce. I was definitely stronger. I’d taken beetroot the night before, and it felt like I’d done everything right for once. I was hydrated, I felt well fed, nothing was hurting. After about half an hour, the leaders started belting back down, having been up to the summit already. Like everyone around me, I applauded the first few but after that thought, sod that, I need to concentrate on my own run. I wasn’t running by that point, and though I managed a shuffle a bit higher up along a flattish bit of the climb, I didn’t run again until I’d got to the summit (in 50:23, on target), profusely thanked all the marshals, perfected my dibbing technique, and set off down. Lovely, lovely downhill. There was grass to run over, clear paths and trods to follow – one of the great advantages of being a middle or back of the pack runner – and it felt like fell running often feels: free and wonderful.

I passed Dave Woodhead at the bottom of the descent. He shouted, “keep up with that big group, Rose, you’ll be fine!” I shouted back, “yes, boss!” and promptly stopped and walked. I’d planned a fuelling strategy and was going to stick to it no matter what. At the bottom of the descent, the ground rises again steeply, and there are steps. That’s where I had decided to take a gel and some water, and that’s what I did. Sorry boss.

After that, there were three or so miles to the next checkpoint of High Birkwith, then another three or so miles to Ribblehead. There were no big climbs, but the route wasn’t flat either. I was supposed to get to High Birkwith in 35 minutes, but I thought I’d been slow and I was: 40.06. I was trying desperately to calculate everything using my pace band and watch, but I was beginning to get confused between the chronological time I was supposed to be at checkpoints and how long I was supposed to take. Was Ribblehead 2pm or 12.30pm and 2 hours? I no longer had any idea. So I just ran, as best I could. There was water at High Birkwith, and more cheery marshals. It’s a very very well organised race, mostly (see next paragraph), and the marshals are all superb.

Whernside

I got to Ribblehead, my results print-out tells me, in 2:04. That gave me a leeway of six minutes. But I didn’t know that. All I was relying on was people around me musing out loud about what time we were doing. I stopped briefly at Ribblehead to get my drink and eat some marzipan and Soreen balls, the better to climb Whernside. Of the three peaks, everyone hates Whernside most, but I was looking forward to it. I’d enjoyed running it in training, and I thought I’d enjoy it again. We hadn’t run the race route in the recce, but FRB said that the route we ran – up a permissive path about 300 metres to the left of the race route – was harder. The race route though had a beck to get through. Some people may leap it, but I walked across it carefully. I didn’t want a daft injury if I could avoid it. Going hell for leather on a descent and getting injured is different: that’s unavoidable. Beyond the beck, through a short railway tunnel (I think: it’s a bit of a blur) there was a queue. About forty runners were waiting at what I thought was a stile. The marshal was Brian, who we’d met at breakfast, and he had clearly landed the worst marshalling job in the race. Because the race route ran through private land. The race organisers spent months negotiating with farmers for access, but something had gone wrong. The farmer had blocked a gap in the wall that was the access point (and that was his wall, though it gave on to publicly accessible land according to OS maps) with a pallet. It was nailed firmly in place. I don’t remember any of this, just the queue, and saying hello to Michael from Pudsey Pacers, who was just behind me. This was unexpected as I thought he was much faster than me. As the wait continued, and mounted up to 5 minutes, the muttering was gloomy. “We’ll never make it.” “They’ll have to make leeway at the cut-offs.” “This isn’t fair.” Etc. One bloke arrived and said, “I’m a runner, I have to get through” to which he got a chorus of WE’RE ALL RUNNERS. The FRA Facebook group and forum has been discussing The Pallet Scandal at great length ever since, including the fact that a man and a well known female veteran runner, who nobody wants to name but I am very very tempted to – her first name rhymes with a word that is a synonym for “flexible” – blatantly queue jumped, running to the front of the queue and going over.

That, quite simply, is cheating. If you arrive later than other runners, then overtake them as they wait, it’s cheating. If you jump over a wall or a field gate when there is a queue at a stile, that is cheating and against the Countryside Code. My club mate Randolph was in the queue when the woman cheater did her cheating, and he said that no-one said anything. Because she’s famous, as famous fell runners go? Or because she was a woman? I really hope I’d have said something. I think I would because I think that is disgraceful. Shame on you, woman whose name rhymes with a word that is a synonym for flexible.

I felt for Brian, who must have had to suffer much complaint and fury. I felt for the race organisers too: there’s no sense that this is a poorly organised race, so something unforeseen had clearly gone wrong. Some very charitable people said perhaps the farmer was well-meaning too, and wanted to make a secure stepping point by nailing the pallet in so firmly. Or perhaps he was making a point about all the runners who during training had ignored the fact of private land and run the race route anyway. As for adding time to the cut-offs, Brian didn’t have a radio, we were about to run into a fierce hailstorm, and after the race I learned that the race organisers were told of the stile delay only five minutes before the cut-off at Hill Inn.

But I had a bog to deal with first. I was definitely tired at this point, because I did something colossally stupid. Before the steep climb up Whernside there is a mile or two of boggy, difficult ground to cover. On the permissive path route I was used to, much of the slopes up to the climb are runnable. I thought these were far less runnable. And I must have decided to test the limits of runnability by not running at all. We reached a bog, and I saw that a runner was stuck in it up to his thighs, and yet I saw a patch of deep clear water and thought, that looks safe. And then both one foot then another sank deep into the bog and were stuck fast. I couldn’t move them. There were plenty of runners around me, so I shouted, “can someone get me out please?” but for a while – it was probably only a dozen seconds or so – no-one did, so I shouted it louder with desperation and hysteria. Michael from Pudsey Pacers and someone else reached in and hauled me out. When I say “haul,” I mean I was dragged out on my face. I have no idea how I emerged with both shoes still on my feet, especially as the one fault of my Roclites is that they are loose on the heels, but I did. I am profoundly grateful to Michael and the other runner for helping me: Thank you.

I was covered in mud up to my waist. I looked like I’d indulged in open defecation, but very inaccurately. But I picked myself up and carried on. I don’t really remember much of the climb, except that it started hailing. Hail. The forecast that I had obsessively checked had said rain. But this turned into a fierce hailstorm. It was so fierce, I started talking to it. “YOU MUST BE JOKING.” Around me, runners were saying, “we’ll never make it now.” “We’ve no chance.” But I thought, if I can get up the steep section OK, I can go at speed on the descent and make up a few minutes. That kept me going for a few hundred feet. And then I decided that what will be, will be. And then I got to the top, and I changed my mind again and tanked it.

I ran as fast as I could along the path, past walkers and more walkers. Once again, the Sikhs were doing their annual charity Vaisakhi walk, and lots of other people were doing the Three Peaks Challenge. I don’t mind walkers, even when I’m running, but I wish they’d keep control of their poles and their dogs. Until we got to the first steep part of the descent, I still thought my tanking plan would work. But then I saw that the path was fully taped, not just in parts, and that marshals weren’t letting anyone go off-piste, either to stop erosion or because with the covering of snow, it was bloody dangerous. We had to stick to the path, and the path was steep, narrow, filled with walkers, and treacherous. This meant that rather than making up time, I was constantly braking, which was loading my joints and knees. But at that point I was concentrating on getting past the walkers. I did a bum slide down one section, as it seemed the most sensible thing to do, and I already looked like I’d had an incontinent accident, so I may as well add to it. It was the one moment where I really really wished I was wearing Mudclaws, because they grip so well on slippy slidy mud. But even with Mudclaws, going off-piste was too dangerous. I came to one very narrow and winding part of the path, and to a group of walkers who had small dogs, both loose. I yelled at them, “please hold your dogs!” I like dogs and I like walkers, but to have dogs off the lead on that path with that many runners coming through seemed daft. We could easily have accidentally kicked or stamped them. But they were probably sick of runners by that point: about 700 must already have gone past them.

I survived the path, got to the bottom, where I knew there was about a mile and a half to go until Hill Inn. I’d long since stopped looking at my watch, but someone said, “we’ve got ten minutes,” and I started sprinting. It felt like sprinting. Later, I found it was nine minute miling. About 500 metres or so from Philbin farm, the place where I’d been patched up after falling on Whernside, a runner came up from the opposite direction. I remember he had grey hair and a nice face. I happened to be running with two other women at the time, and he decided to take us all on. “Come on ladies,” he said, “you can do it. But you need to push. PUSH.” He ran with us all the way to the checkpoint. It was bloody awful. I felt like my lungs were going to come out of my ears. I felt like crying. At one point I’m pretty sure I was crying and running. It was less than half a mile but it felt like so much more. I was panicking and running, panicking and crying, running and crying. As I approached the checkpoint, a man said, “ONE MORE MINUTE” and I had made it. I had made it by the skin of all my teeth.

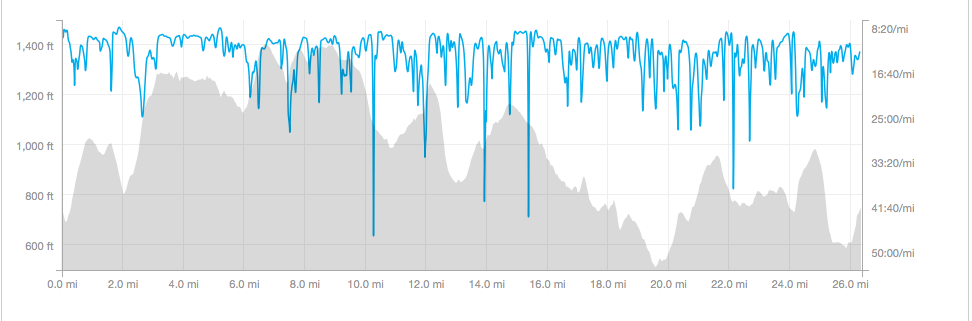

Ingleborough

I couldn’t believe it. I had a massive grin on my face which stayed there for the next mile. I realised that I had probably never really thought I’d make it. But now the pressure was off, and I could relax a bit. I told myself I didn’t care what time I finished it, though actually I did and wanted to beat FRB’s first Three Peaks time of 5:37. So I kept moving, to find my flat Coke, and I watched a man vomiting copiously near me, and I thought, god, I am tired. I was so, so tired. I must have hung around at the checkpoint for a couple of minutes, but finally I set off again. I saw my club mate Adam, covered in blood and mud. He’d fallen on Whernside. He’s much faster than me normally, and I thought it odd that he was still at the checkpoint, but doing the Three Peaks for the first time can catch everyone out. We set off walking up to the stile that led to the Ingleborough path. Over that, and then there was a mile or so of runnable fields.

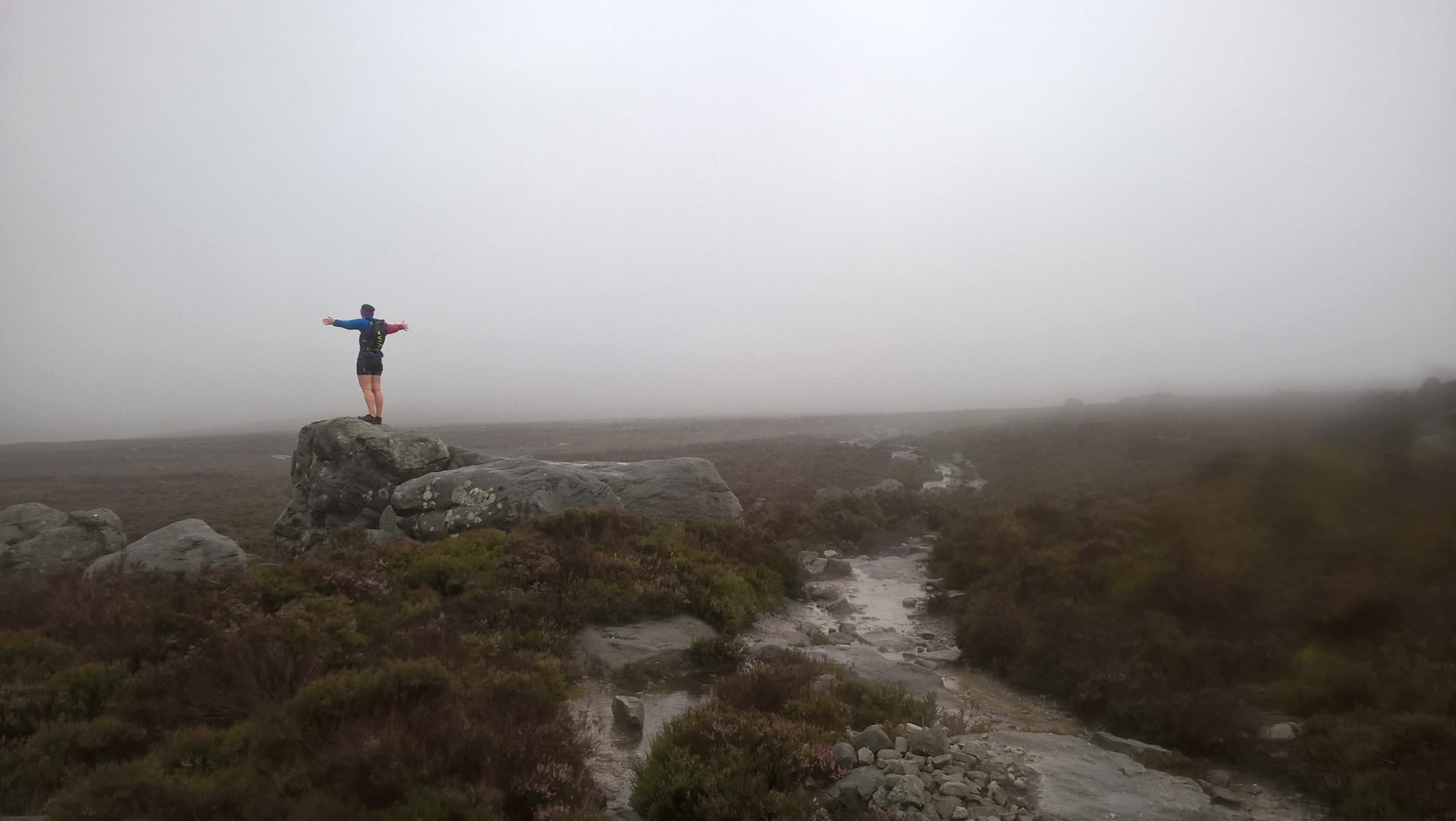

Stuff that. I was walking. Adam ran off, and got back 15 minutes before me. But my inner thighs were cramping, which was bizarre, as I’ve never had running cramp before. And I was tired and still had two thousand or so feet to climb, and a difficult descent, and five more miles to run. But I still had that grin on my face. I’d made it. Even if I did it in six hours, I’d made it. And that kept me going. I ran a bit, walked a bit, ran a bit, walked a bit. I saw a sign saying that SportsSunday, sports photographers, were round the corner, so I picked my pace up, stuck a smile on my face, and was rewarded with first “that’s a cracker!” from the photographer, and this lovely photo:

See the state of my gloves? That was from the bog. But I was still wiping my nose with them. It was cold enough that I kept my waterproof on, and I knew it would get colder. Eventually I got to the foot of Ingleborough. It’s a rocky tricky technical climb up, and as I approached the start of the steep climb, I saw a line of runners snaking up and up and up. It looked so high. But actually it was fine. It was the last one. I got to the top in 56 minutes, almost exactly the same time as I’d done Whernside in (you’re supposed to do each peak in roughly the same time). Along the way I helped a walker who was slipping, and I think chatted to other people but now I can’t remember any of it. At the summit, I thanked the marshals loudly. It’s the longest marshalling stint: they can be up there for 7 or 8 hours, and it was COLD. There was snow everywhere. This film by my clubmate Adam Nodwell gives a very fine sense of the whole race.

But you know what? At the summit, THERE WAS NO MORE HILL TO CLIMB. Blessed, lovely descent. I set off, passing another runner who I turned to speak to, and saw that it was Dave Burdon of Pudsey Pacers. Dave is 60 and has run the Three Peaks eight times, I think. I knew he planned that this would be his last one. We decided to run together to the finish, and I’m so glad we did. That sounds so simple, doesn’t it? “Run to the finish.” But the last four and a half (or maybe five) miles to Horton are very difficult. Your legs are exhausted, but you can’t take your attention off the terrain for a second. There is the steep descent of Ingleborough, which starts off rocky then turns slushy and grassy with snow as well. If I’d been able to see the ground, I could have gone off-piste again, but there was no chance here. I wasn’t going to fall at this point. Dave was great to run with: he told me constantly what was coming up. “Flagstones, here, Rose, they’ll be slippery.” “Technical bit here, Rose.” I’m quite sure I’d have walked more if I’d been running on my own, but with Dave, we ran steadily, all the way back.

I almost forgot Colin. Coming off Ingleborough, or perhaps going up it, I passed a couple with a collie dog. They called the dog over and I said, “Colin?” “Yes,” they said. “Colin the collie.”

Of course.

There were rocks and gullies, and grass, and heather, and mud, and a checkpoint with water, that was very welcome. There was a moment where Dave had to stop because his legs were badly cramping, but he had one of my marzipan balls and recovered enough to run on. Magic marzipan. Later, I found out that Ben, another Pudsey Pacer, had collapsed at about this point, and had to sit down for five minutes while Mountain Rescue fed him chocolate. He said it was astonishing how soon after he’d eaten the chocolate that he felt better. You can’t run a race like the Three Peaks without knowing how your body works and what it needs. It’s too risky. But he got up and ran on and did a great time, so well done Ben and well done Mars Bars.

At about a mile from the finish, it seems like you are in a bucolic vision: there are green rolling hills, and you can see the village of Horton in the distance. Two Mountain Rescue people stood near a stile saying, “only two more hills!” and they were right, though they were more like inclines. But they felt like mountains. We got ourselves up them, over the field, over another field, under a railway bridge, through someone’s garden. I’d been warned about this bit, that there would be chickens. It’s probably a good thing because otherwise I’d have thought I was hallucinating. But the chicken coop was empty, probably emptied by all the thundered cleated feet. And then, holy cow, there was the finish line. A woman over the PA was presumably reading out the cute anecdotes that you put on your entry form. Mine was something about learning to run on a container ship and being good at swaying. But she could have been singing the national anthem and I wouldn’t have noticed at that point. All my attention was focused on the dibber. The final, beautiful dibber.

I got round in 5 hours and 24 minutes. I beat FRB’s first-year time. I couldn’t stop grinning. FRB had beaten his time by a minute, which in that weather counts as ten. He told me that for 20 minutes or so, he thought I hadn’t made it, because the screens in the marquee that track people’s times through checkpoints showed that my time at Hill Inn was 3 hours 30 and a few seconds. Until I got through Ingleborough and that went up on the board, he thought I hadn’t made it. He said he felt so despondent, then our fell-running friend Sharon – who was supposed to have run the Peaks, but unsurprisingly hadn’t quite recovered from running the 60 mile Fellsman in an amazing time two weeks before – ran up to him and said “Rose is through! She’s gone through Ingleborough!” And he was elated.

Dave Woodhead was in the finish area with his camera. He took pictures of me, then of me and Dave Burdon, then of Dave, then of I can’t remember who. He went off then called me over. I did as I was told, because you do what Dave Woodhead tells you, mostly. Then he called two other blokes over and made me stand between them. “Do you know who these men are?” he asked. I didn’t. But at that point I’d barely have recognised Mo Farah. Dave said, “this is Harry Walker, a fell running legend. He’s won the Peaks three times. He’s in Studmarks on the summits.” I said, sorry, I hadn’t read Studmarks but was he in Feet in the Clouds? The other man is John Calvert, who used to run cross-country for England, who has also won the Three Peaks and still holds his club’s 10 mile record, thirty years after he ran it. Anyway I love this picture, and I also love the fact that Harry, who was as puzzled as me as to why Dave was asking us to pose together (a rose between two thorns?), said, “were you first lady?” Yes! If you don’t count the other 677 runners (not sure how many women) who finished before me.

Marc Lauenstein, a dentist from Switzerland, came first, Ricky Lightfoot second. Victoria Wilkinson was first woman, Mira Rai came second. And I made it, and though I say this far too rarely, I am proud of myself. The Three Peaks is not just one of the toughest races I’ve ever run, but it’s one of the hardest challenges I’ve set myself. I’ve had a difficult and troublesome six months, with my mental health and menopausal symptoms, and yet I kept going, and I did it. I am deeply grateful to everyone who encouraged me along the way, and especially of course to FRB, who ran a brilliant race himself, and who has been unfailingly encouraging, supportive and wonderful through the last six months of hard training and hard health issues. Thank you, FRB.

So if you’re thinking about taking something on but you don’t think you can do it, you can, whether it’s going from running no miles to one, or from 13 to 26.2, or giving a speech, or writing the first paragraph of your book. You just can. See you in a field in Horton next year, or whatever your field consists of.

Image: FRB

Image: FRB