There are harder jobs than writing books. Trauma surgery, or being a Conservative politician who manages to keep her or his job. Truck drivers, nurses, teachers. So many people are what is called time-poor. I have more freedom than many people – that’s why my job is called free(lance) — but writing a book, when it comes to the writing period of it, is still intense. For several months last year, I wrote 100,000 words and spent weeks on end at my desk from 7am for twelve hours a day. I had no social life and FRB forgot he had a girlfriend. I sent that draft in in autumn, and got fitter and did Tour of Pendle and got a massive PB. In January, the book began to come back from my editor, and there began another few months of rewriting, re-researching, doing more interviews. I tell myself that the next book will be one that doesn’t require me to understand medicine or science, neither of which I’m trained in. But this one does, and it was hard work.

The long, the short and the ugly of this is that I didn’t follow my Three Peaks training plan.

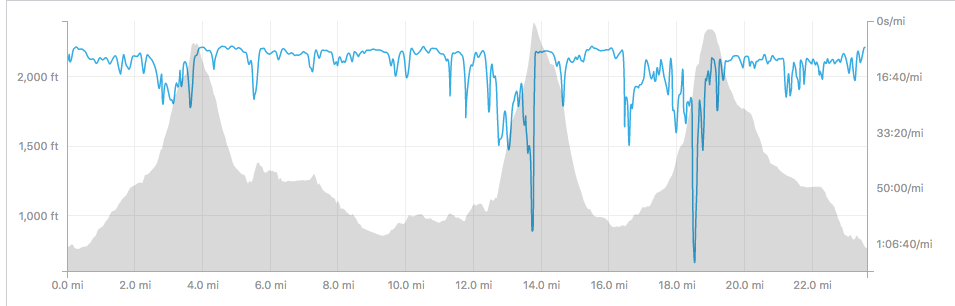

Of course I had one, because my partner is Coach FRB and he does excellent bespoke training plans. Hire him. Although I kept a base level of fitness with a weekly spin class, a weekly weight-lifting class and a couple of runs a week, I neglected to do the tempo, interval or hill sessions or long runs. Quality not quantity was the essence of the plan. It was meant to address all the skills necessary to run the Three Peaks, because there are so many. Climbing ability, obviously. But also good technique to descend over slippery, rocky ground. Speed, to get between the peaks inside the cut-offs. Stamina, to get through the cut-off at Hill Inn, look up at Ingleborough and not cry but then run another 8 or so miles. My plan covered all these skills, and I did hardly any of it.

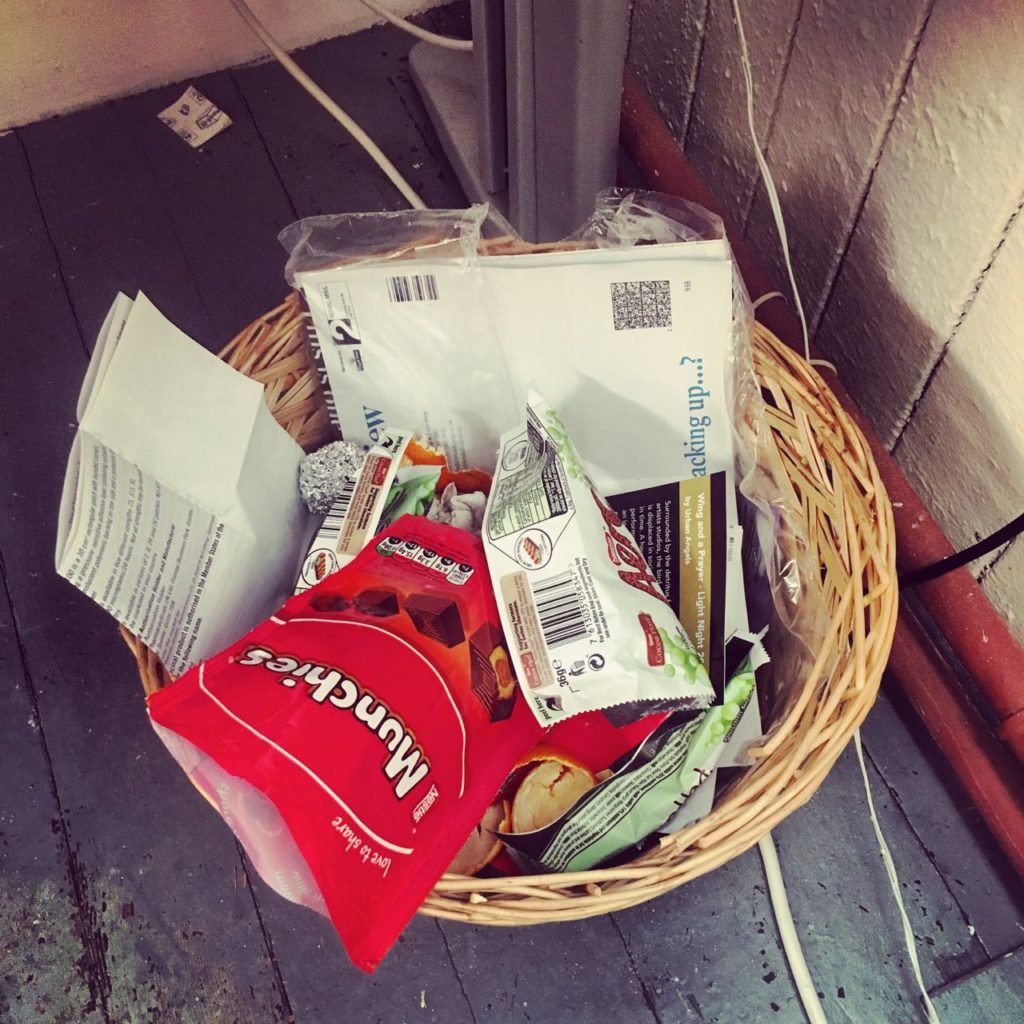

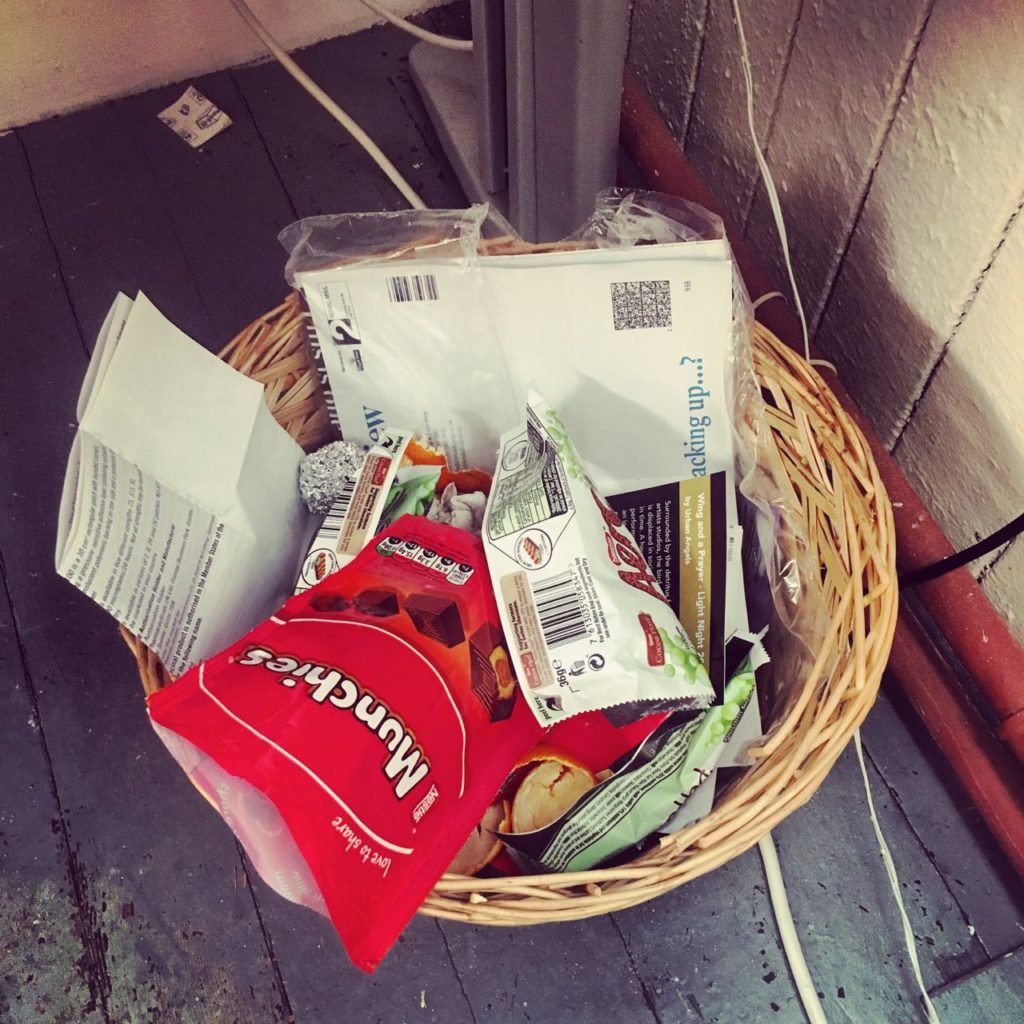

Throughout the writing period, I’d also consumed far too much chocolate and cake. You take your small comforts where you can, and when I was stuck at my desk all day every day with very few outlets, my comfort became the subsidised vending machine downstairs, and pickled onion Monster Munch. This was all visible on what is known as “writer’s butt,” and on what I call my “hockey legs.” In this case the word “hockey” is a euphemism for “chunky.” FRB tried to encourage me. Your legs are powerful, he said. They will get you up hills. Yes, but my bin:

I finally sent in the second draft of my book a month before the race and took a long hard look at myself. I had put on weight. I was undertrained. I was pretty sure I wasn’t going to run the Three Peaks and told everyone as much. I didn’t want to run it and do badly, I said. I’d rather do it in peak fitness, I said. The state I’m in, I won’t even get past Ribblehead, I said.

—

April 28, 10.30am. Here I am again in a field in Horton, about to attempt what the organizers call “the circuit of the summits of Pen-y-Ghent, Whernside and Ingleborough.” Here I am again, about to attempt the 64th Three Peaks Race.

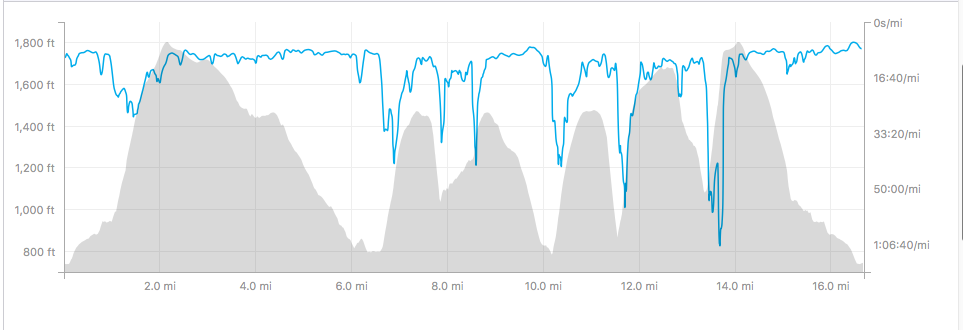

A month earlier, though I was convinced I’d never be in good enough shape to run the race, I had made a plan. I would train as hard as possible in the time remaining, and then make a decision on April 21, with one week to go. I did this. I did longish runs, hill training, more hill training, tempo runs. It didn’t begin well: FRB and I celebrated my freedom-from-my-desk by going to Addingham and climbing the steepest side of Beamsley Beacon. The face is almost as steep as Whernside in places, a hands-and-foot ascent. We followed this by three miles of tempo running, then ran another eight or so miles. A lot of those miles were uphill but still I felt absurdly broken. After the tempo section, I barely ran. I thought, this isn’t even half of what I’ll have to do on race day, even on the first leg. Speed is never my strength, and the six miles between the bottom of Pen-y-Ghent and Ribblehead are always a challenge. Even if I make good time getting down PYG, I can lose it on that stretch. I was despondent.

But slowly, over the weeks, I began to feel fitter. I got to the point where I’d see a hill that I didn’t need to run up and run up it anyway. I was still carrying too much weight, but there wasn’t much I could do about that in time. On the 20th, I decided to do the race. I thought my chances of getting to Ribblehead were slim, and slimmer for Hill Inn. Me, though, I wasn’t slimmer. But I would try to get round the race anyway. God loves a trier.

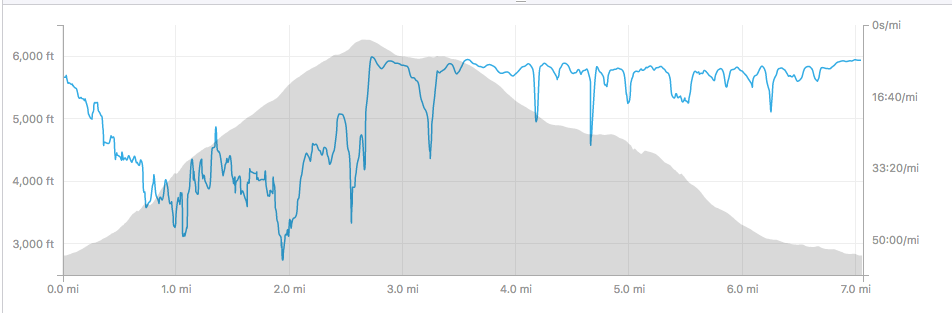

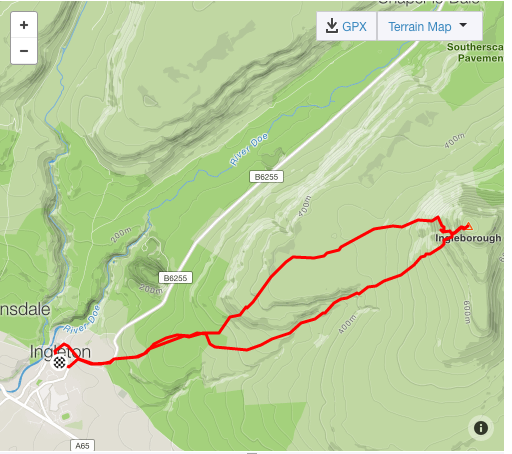

I did a couple of recces in the Peaks. The first, with my old club-mates from Kirkstall Harriers and FRB. And the second with Laura, a second-claim Kirkstall Harrier (like me) who was doing the race for the first time. We decided to do Whernside and Ingleborough, and to ascend Whernside by the permissive path that runs up about 300 metres parallel to the race route. Runners aren’t supposed to use the race route before race day: it’s private land and lambing season. So it was disconcerting to watch a male runner overtake us at the viaduct and and then head up the race route. Unless he is close friends with the farmer and had permission — this is not impossible — that was a reckless thing for him to do and could have ruined the race for everyone.

For the first time in a few years, FRB had decided not to race. Instead, he volunteered to marshal on the top of Pen-y-Ghent, so this would be a mirror situation of 2015, when I was up there freezing and marshalling, and he was running. He headed up to Horton a couple of days early to help our friend Martin, who is course director and marshal-organizer.

So on race day morning, I was alone. I woke absurdly early, though I’d slept well. I’d eaten well too, for the previous few days. I was unsure of my running ability, but I could control other aspects of it. Last year I hadn’t eaten enough before starting, nor throughout the race. This year, I planned very carefully what I would eat and where. A gel at Whitber Hill. Another gel on the incline up to the Ribblehead road. A Quorn cocktail sausage – for the salt content – at the viaduct steps, so that I wouldn’t cramp again at the summit of Whernside. Chocolate at Hill Inn, and something else at the foot of Ingleborough, if I got that far.

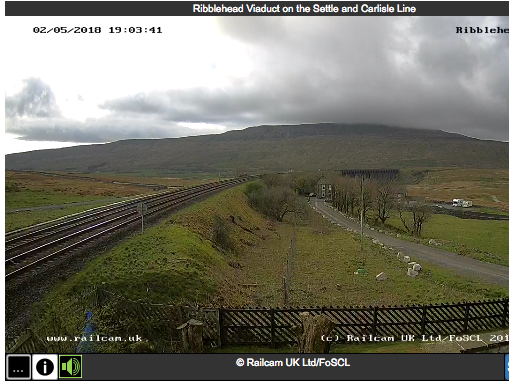

It was a beautiful day. Of course I had been checking the forecast and the Settle & Carlisle railway webcams all week.

Mid-week, the forecast had predicted fierce winds on the top of Pen-y-Ghent. 30 miles an hour in the wrong direction. But this calmed down, and on the day there was hardly any wind, the skies were clear and sometimes overcast, both of which were fine, and the temperature was cool enough to run in comfortably. I wore a t-shirt, vest and shorts, and I was never cold. The weather, in my view, was as perfect as it could be.

I saw FRB on the road in Horton as he headed up to his marshalling position, but there was no room to stop, so there was no last-minute coaching or hugging to be done. I could have done with the hug. Instead, my pre-race prep consisted of seeing lots of people I knew and watching them not recognise me (different hair, new glasses). This passed the time. My friends Louise and Laura were both doing the race for the first time. Louise was nervous, Laura was nervous, so I thought I’d better act like I wasn’t. Laura had written the cut-offs on her arm. Clock time first: 12.40 to Ribblehead, 2pm at Hill Inn. She also had the elapsed time she needed to do: 1 35 to High Birkwith, 2.10 to Ribblehead, 3.30 to Hill Inn. I remembered the first year, when I’d done the same thing and got thoroughly confused, and thought I had to be at Ribblehead at 2.10pm. I advised her to stick to elapsed time.

The parking monitors had directed me to the furthest field, by the river – anyone who knows Horton will know it as the field with all the hens in – and it was quite a walk. But walking calmed me down. I got ready, quite serenely, and remembered to eat some Soreen. I headed back to join the huge toilet queue – where I watched with annoyance as men blithely used the ladies’ toilets – and then it was time for kit-check and race briefing. The kit check was not rigorous, which is odd when runner safety is held so precious that we had to give photo ID to collect our race numbers (so that no-one could turn up and wing it). A man looked inside my bag, agreed with me when I said, that’s my trousers, jacket, hat, gloves and didn’t check that my race map was a map of this race or in fact the Timbuktu 10K. I also think one gel – which was all he could see, though I had plenty more food – does not count as adequate emergency food for a 23-mile race.

Into the marquee, to the fragrant smell of bacon sandwiches and Deep Heat. The race briefing was given by Paul Dennison, who has been race director for years. The stage had been moved so that more people could hear the briefing, but I was at the back, doing the only warm-up I had time to do (dynamic stretches and a lot of jumping) and I still couldn’t hear a thing. I moved forwards and managed to hear some of it, including him giving the wrong cut-offs, before someone corrected him. He gave them according to clock time, which I don’t find useful anyway. He also said that we had to stick to the path at Bruntscar coming off Whernside, because otherwise we would annoy the farmers. Any runner who disobeyed this would be disqualified.

To the start, then. I watched with some surprise as one runner near me inserted earphones and switched on a music player. Headphones aren’t allowed in the race and wearing them can get you disqualified. Nobody else had them, which should have been some clue. But the race was about to start, and I didn’t say anything, and she didn’t get disqualified. I was really pleased that both Ian and Alan from Keighley & Craven, with whom I run in plenty of races, were doing the race. Alan is my Tour of Pendle Twin. We are sort of evenly matched on pace, and our race efforts pendulum between him beating me and me beating him. I guessed today would be a victory for my twin.

Pace. I had to get my pacing right. I couldn’t set off too fast and be depleted for PYG. I couldn’t go too fast up PYG and be depleted for the Ribblehead stretch. I couldn’t go too fast to Ribblehead and have nothing left for Whernside, but I had to have enough wiggle room – the more, the better – at Ribblehead so I had more time to get off Whernside, especially if we had to stick to a highly technical rocky path stuffed with walkers, dogs and sticks, and to Hill Inn. All this translated as: go steady. We set off, up out of the field, along the road, round the corner, and I looked up for once, and saw a mass and stream of runners ahead of me. I had three thoughts:

- What an amazing sight: all those colours.

- I’m at the back.

- I’m staying at the back.

People passed me but I didn’t mind. I didn’t have a minute-per-mile pace in mind, because mountains make a nonsense of that, but when I looked at my watch on the road and saw I was doing a 7.30 minute mile, I slowed down. These were my race tactics

- Go steady.

- Don’t lean into the hills.

- If you are out of breath, then walk.

- Don’t look at your watch too much.

This was the first time I’d trained at walking faster. I experimented: standing tall with fast arms, or the fell-runners’ crouch. Both are good for different gradients.

There was the usual bottleneck at Horton, then it was up to Pen-y-Ghent.

—

Pen-y-Ghent

It is the smallest of the Yorkshire Three Peaks, at 2, 277 feet. It is made up of millstone grit on top of carboniferous limestone. The summit acts as a watershed with water flowing into the River Skirfare to the east, then to the Humber Estuary. Westwards, water flows into the River Ribble and to the Irish Sea. Pen and y are from the Cumbric language, a Common Brittonic language spoken in the Old North and related to Old Welsh. They mean “head” and “the”. Ghent may mean border or winds. Pen-y-Ghent: the Head of the Winds

It was such a glorious day. Runners were dressed in all sorts: some in full body cover, some in vest and shorts. I looked up to the mountain and saw a yellow paraglider, which was beautiful and free and so, so far away. Never mind. Alan-the-twin was staying with me, and kept saying, “come on, kid,” so I did. I could see Laura up ahead, and I knew Louise was up there too, but I thought that if I managed to stay in the race and not be timed out, I might catch her up. She’s very good on flat and undulating terrain, but still working on her descending.

Shoes: of course there had been the shoe question. FRB had been out and about flagging and taping the course. He reported that the ground was extremely wet and sort of advised Mudclaws. Hmm. The grip would be good, but the course has far more hard surface than soggy surface. So I stuck with Roclites, and they were mostly fine, except for slipping on rock.

On the way up to the hairpin bend, the elites started coming down. I cheered them, and Victoria Wilkinson, and then I shut up and concentrated on getting myself up. Compared to last year, I felt great. I felt rested, and fed, and hydrated, and I was enjoying it. At the hairpin bend, I found Mike and Tim of my club, who were marshalling. Mike cheered me on, Tim cracked a joke about me getting lost. Even I can’t get lost on this race. Because the marshals are organized by Martin Bullock, who runs for Pudsey Pacers, I knew that a lot would be from Leeds clubs. I knew I’d have friends at most checkpoints, and I was hoping to be a fit state to greet them properly. Upwards.

My twin is the bloke with the beard. The other fellow is my Lost-Mate from Heptonstall. Both of them beat me.

My twin is the bloke with the beard. The other fellow is my Lost-Mate from Heptonstall. Both of them beat me.

I walked when I had to, shuffled when I could, and got myself up the newish stone steps that some people don’t like. I like them better then I like erosion. I looked at my watch and saw that I’d done it in 50 minutes, which I think was on target. And there was FRB in the distance with his dibber. I dibbed, we kissed, I ran off. He told me later that his fellow marshal said, “Is that your girlfriend?”

And he said, “No, she’s still to come up.”

I love the descent of PYG: there’s a nice soft bit, a tricky rocky bit, then a pelting down on a relatively clear path. So I shifted, and I felt good. I got cheers from Adrian and Cathy of Pudsey Pacers, who were marshalling at the first gate, and these were the first cheers of many. On the stretch to Ribblehead, the race field has settled, and you’ll start to recognise people running around you. I got chatting to a few, including Rachel, a woman from Milton Keynes, Jacqui from Shropshire, and a man who I greeted by saying, “great hat. You look like a goblin.” Surprisingly, he didn’t take offence but told me he had grown up in Leeds, lived in Munster in Germany, which is flat, and had trained by walking in the Alps. I also started chatting to one man I thought I recognised as a Pudsey Pacer, and told him that I was with FRB and blah blah. After the race I realised his yellow vest belonged to a club in St. Alban’s, and he’d had no idea what I was on about. Sorry, Jim.

The checkpoint at High Birkwith was marshalled by yet more Pudsey Pacers, and the people running near me began to look at me: who are you?

The answer is: I’m from Leeds.

When I introduced myself to Rachel, she said, yes, I know. Then, “I’m thinking of changing my name to Rose.”

I caught up with Laura on Whitber Hill and yelled at her to fuel, because I know she sometimes forgets. Then I looked at her face. “How do you feel?” “Awful.” She said she had cramp, and that she wanted to drop out. I could see that she was talking herself out of it. I put on my stern FRB coaching voice. “Laura, you are an excellent runner, and you have a strong brain. It’s your brain that will get you round. Start running.”

Then, “RUN.”

I kept turning to look, and she was running, and I was pleased for her. I got to High Birkwith slightly over target, but that was immaterial because I couldn’t remember how many miles I had left before Ribblehead. So the only thing to do was run as fast as I could. I still felt great. By that I mean, my legs set off running on their own, a sure sign that I’m feeling good. I ran inclines. I kept moving. I made sure to eat and drink. I saw my friend Sara, who had run Three Peaks for the first time last year and triumphed, and this year was marshalling, and ran towards her with my arms wide open for a hug. It was a very welcome hug though I probably looked like a madwoman. Even so, when I got to the road, nearly two hours had passed, and the cut-off was 2.10. Oh. It’s a busy road that motorbikes use for a testosterone workout, along with the rest of the Yorkshire Dales. Some are the kind of motorcyclists who have caused trauma staff to call motorbikes donorbikes (frequent deaths by head injury, salvageable organs). I heard later that a motorcyclist had zoomed past the marshals at 50mph, into oncoming runners. Unprintable words here.

The tiny incline up to the checkpoint at Ribblehead felt as implausibly steep as it always does, but I got up it, and over the road, and there were my mates and fellow Women with Torches Caroline and Sharon shouting encouragement. A few hundred metres earlier, I’d suddenly remembered that I’d put both my bottles – you can leave one bottle at Ribblehead and another at Hill Inn – in one bucket. But which? Luckily I was running with copious amounts of liquid and a full picnic, so I wasn’t worried. There was no bottle at Ribblehead. I stopped to talk to Emma, who was marshalling, another Kirkstall Harrier, and said I didn’t think Laura would make it. I wasn’t doing her down, but even though she’d started running, I’d lost sight of her and I wasn’t sure she’d make up the time. She did though, and got through Ribblehead and up and down Whernside, which considering how low she had been feeling, is impressive. To be feeling awful, and to run five miles at speed, then get up and down a punishing hill: that is a massive achievement. (She was timed out at Hill Inn, but she’ll be back.)

—

Whernside. Ah, Whernside.

The highest of the Yorkshire Three Peaks. The highest point in the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire. Two thousand, four hundred and 15 feet. From its summit you can see to the sea. Whern, from querns or millstones. Side from the Norse sætter, an area of summer pasture. Modern day descriptions of Whernside include “a whale” and “a long, slumbering monster.”

From where I was, running along the track to the viaduct, Whernside looked not like a whale, not like a monster, but like a lot of pain and effort. It looked like a mountain. One tourism website wrote “it is prone to all those fit-types zooming up and down it, so it can feel a bit like the M25 during rush-hour.”

I was definitely not zooming, but I was shuffling where last year I’d walked. I felt tired but OK. On the steps, there were some people shouting, well done Alan, and I turned round and there was my twin, his knee bloodied, but right behind me. I was astonished. I hadn’t seen him since Pen-y-Ghent, so he must have had a storming run to Ribblehead. We ran together for a bit, but once we were through the beck, through Palletgate-gate (blessedly open again) and began the long slog across the bog, he overtook me and I didn’t see him again. I managed not to get stuck in a bog, but I didn’t enjoy this bit. It’s such a long way to the steep climb, and the ground was sodden and it sapped my legs. Every time I looked up there seemed to be another climb ahead of me. I did what I do when I’m flagging, and counted. To 50, then a rest. To 50, then a rest.

I got to the summit in just over an hour, which left me less than half an hour to run the 2.5 miles to Hill Inn. That would be very easy if it was a clear and smooth path. But I knew it wouldn’t be.

I began to stress and panic, enough that I failed to recognise Olly, Martin’s nephew, who was handing out jelly-babies (I’d also failed to recognise Charlie Mac and Graham P on PYG, and I wasn’t even depleted then.) At least my legs had not turned into peg-legs, so I set off as best I could. Along the ridge, then down a steep technical bit, then onto the path. There were loads of walkers, but they were kind and moved out of the way (they could have seen more than 600 runners by then so had practice. They would also have been entitled to be grumpy, but they weren’t). The path went on and on and on. Rocks, flagstones, more rocks. Thousands of boulder-sized hazards; thousands of catch-your-shoe stones. I knew there was lovely soft ground to either side of the path, but it was beyond the course tape and off-piste meant disqualification. I stuck to the rocks.

Eventually I got to the final gate and the tarmac stretch to Hill Inn. I didn’t have much time. Suddenly I was a bit baffled as to how this had happened: I’d felt so good, and I thought I’d been running well, and yet here I was still with a serious risk of not making the cut-off. (Race analysis: I lost time where I usually lose time, between PYG and Ribblehead). I hadn’t liked the Whernside slog but my feelings about that were nothing compared to how I detested this last mile and a half. It was horrible. I was running and panicking and running and panicking. I’d had more time the year before. This felt like the first year that I’d run the race, when a kind man had come and run alongside me to the finish. The incline up to the farm looked like a mountain and there was no kind man coaxing me up this year. But I ran up it and I kept going and tried not to give up when someone said, run to the flag, and I saw a Union Jack flying but it looked like it was in the next county.

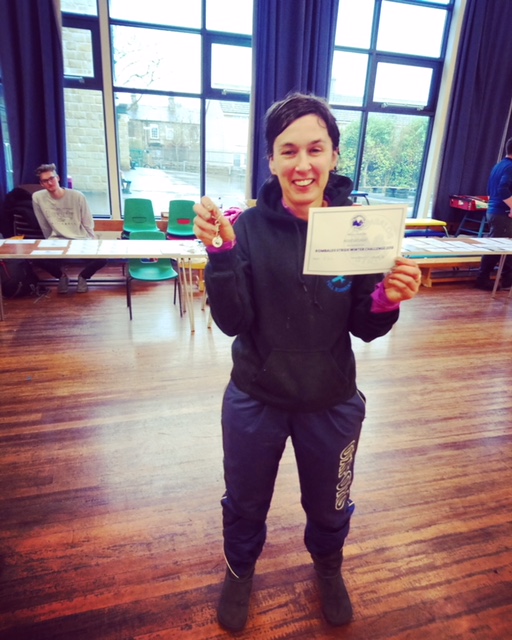

I made it. 3 hours 30 minutes and 29 seconds. They let me through.

I was dazed. I’d never really thought I’d make it. But I made it, on only three weeks of proper training and rather a lot of Yorkshire grit.

There and then I thought, I’m not doing this again. I’m never doing this again. It’s not worth the stress.

My friends Niamh and Andy were at the checkpoint, and directed me onwards. When you arrive so close to the cut-offs (although they relaxed it by a few minutes) marshals don’t want you hanging round in case they have to time people out and people say, but you must have just let that runner through. Jill from Kirkstall was also marshalling there and she said it was heartbreaking. Some people take it well; some are bereft. This is why I don’t like references to the Bus of Shame, supposedly the nickname for the minibuses that transport people who have been timed out. There is nothing shameful about having run either one peak or two, or having done your best.

I picked up my two bottles and thought the best thing to do was to carry them, and I headed up to Adductor Stile. This is the stile into the fields that lead to Ingleborough, and it always gives me agonizing adductor cramp. This year was an improvement: only one leg got it. I hobbled around in considerable pain and asked Tony, another Pudsey Pacer marshal, what to do about it.

“Dunno.”

There’s no reason he should have known. They don’t hand marshals a degree in sports medicine along with the hi-viz. But I was desperate for advice. In the end I did the only thing I knew, and kept walking, and it wore off. My friend Louise, who I’d caught up on Whernside, had got through the cut-offs behind me, and there was now a group of five women together, including Jacqui and Rachel. It was companionable and nice.

Each time I run this race, I promise I will do better with Ingleborough. I swear I won’t walk all the way to the flagstones. Each year I walk all the way to the flagstones. Not quite, but I did walk a long way. When I compared my times to Nicky Spinks, she took 35 minutes to get up Ingleborough and I took an hour. But I was so happy I’d got through I didn’t much care about times. I usually feel like that until a mile from the end when I realise what my finish time is going to be, and wish I’d made more effort.

Ingleborough. It is the second largest of the Yorkshire Three Peaks, at 2,415 feet. Borough is from burgh, for fort. Ingle may be from Angle. The summit shows the remains of a hill fort, probably built by the Brigantes and known by the Romans as King’s Fort. Along the Three Peaks challenge route to the climb, there are many caves including Great Douk Cave and Meregill Hole.

For now I just drank and fuelled. Rachel was cramping and asked if anyone had salt, so she got my bottle of electrolytes meant for Ribblehead. She turned down a Quorn cocktail sausage. The ascent to Ingleborough was the same as ever: steep, and rocky. We went up alongside walkers, and I ran when I could, and was patient otherwise. At the top, where the path narrows, there were a handful of marshals, and it was busy with walkers. One of the marshals yelled, “Walkers! You’ve got to give way to runners!”

I disagreed with her. We share the mountain. Walkers didn’t have to do anything. Behind me, a group of lads from Liverpool were cursing at her and I said mildly, no need for that language. Swearing on the top of a mighty mountain in fresh air on a glorious day seems as ugly as smoking. An air turned blue, an air polluted. They apologised, and we began to talk. This was their third peak, they were exhausted, and they hadn’t taken kindly to being told what they had to shift out of the way, quickly, when their legs were as tired as ours. It was fair enough. We got to the top, I began to shuffle again, and we parted as friends who had climbed the same mountain.

Friends. I spend a lot of races running alone. This isn’t one of them. I’d made friends along the route, I’d seen friends at every checkpoint. A thing, also, that I love about fellrunning is that it doesn’t matter what people do away from what we are doing together. I run with nurses, teachers, labourers, electricians, HGV drivers, all sorts of people I wouldn’t otherwise encounter. And now I had still more friends to meet: Jenny and Dave were at the summit checkpoint. Ingleborough is a thankless marshalling post: you head up early (I’d seen Jenny and Dave leaving Horton at 9), it takes five miles of walking each way, and they stay there until the last runner. Luckily for Jenny and Dave, I wasn’t far in front of the last runner, so their escape was in sight. I grabbed some jelly-babies and set off, overtaking Louise and Jacquie to the sound of “there she goes, we won’t see her again.” A lot of people dislike the last stretch to Horton, but I like it. For a start, there are no more mountains to climb. And I like the fact that my legs still work, and that the body is an amazing thing. Being able to run for five miles after all I’d done, even though it was me doing it, astonished me.

FRB had shown us a good route down, less rocky, but in my tired state I couldn’t remember whether going off-piste was also a DQ offence here or just at Brunscar. So I stuck to the route that the marshals were shouting to me to take, though it was an awful one: slippery, technical rock. I managed not to fall, and I managed not to fall all the way back, that long, long path of treacherous rocks large and small, of limestone cuttings, of pitfalls and hazards. Finally I recognised where we were and said to Rachel, “this is the best bit.” It’s the view down to Horton. The giant white marquee. The sight of the end. Then it was another mile or so, up green fields, down green fields, through a tunnel, over the road, and the finish. Rachel and I finished together, and I remembered to have my number visible so that the announcer knew who I was. Of course I was so exhausted I didn’t listen to the announcer. The final dibber, and I collapsed onto FRB.

—

After that? A change of clothes, which meant walking all the way back to the car as I’d forgotten about the changing tents. Back to the marquee for food and a debrief. FRB told me he had been trying to track my progress on the screens, but they kept failing. So Martin went to the results tent and found out that I’d got through Hill Inn, and FRB punched the air. He said, as we sat at the tables with our veg chili, “I didn’t think you’d get past Hill Inn.” I’ve told people he said this and they have looked surprised. I take it as it was meant: he was worried I wouldn’t make it, but extremely impressed that I had.

I drank a bucket of tea. I’d been dreaming of tea for a few miles, enough to use it as a metronome.

Cup.

Of.

Tea.

Cup.

Of.

Tea.

Finally we headed back towards the field where the car was parked. Most cars had gone. I’d finished in the last brace of runners. 686th out of 701. There had been 760 starters, some had retired, probably about 50 had been timed out at Hill Inn and Ribblehead. My position in the race meant that most cars had departed, so that when we walked through the gate into the field, there was my car, almost alone in the far corner, surrounded by the hens that had been released from the hen-house, the boot wide open.

I said, oh.

But because fell runners are a wonderful group of people, no-one had stolen my expensive race-pack or my expensive Stormshell jacket, or my three pairs of shoes. Thank you fellow runners.

Afterwards, FRB said that he thought this was my highest running achievement. He kept saying, “on three weeks training,” in some wonder. I’d had base fitness, and done some stuff, but yes. I did the Three Peaks race on three weeks training. When I compared my splits to last year’s, they weren’t far off. I got my pacing right. I got fuelling right. The organizing committee had ordered the right weather. I only took two minutes longer to get from Whernside summit to Hill Inn than FRB, and I did it quicker than I ran it last year, when I did go off-piste.

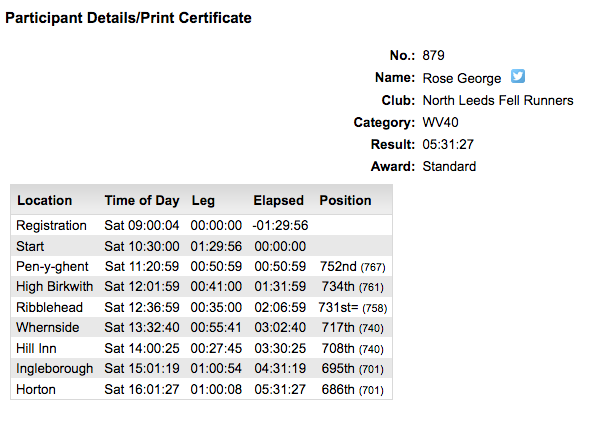

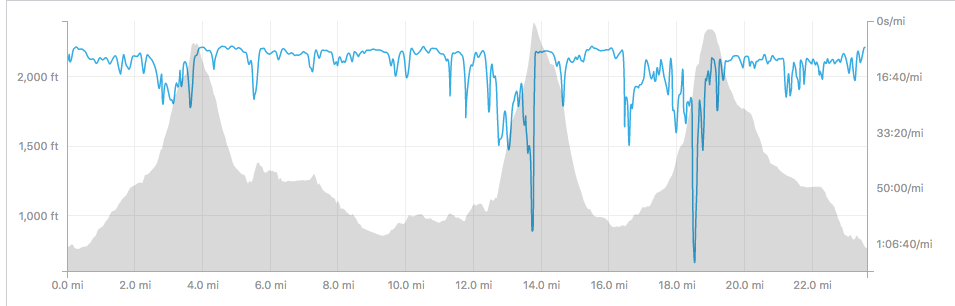

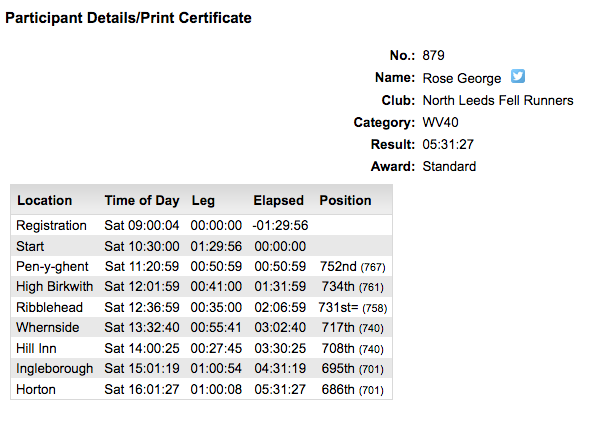

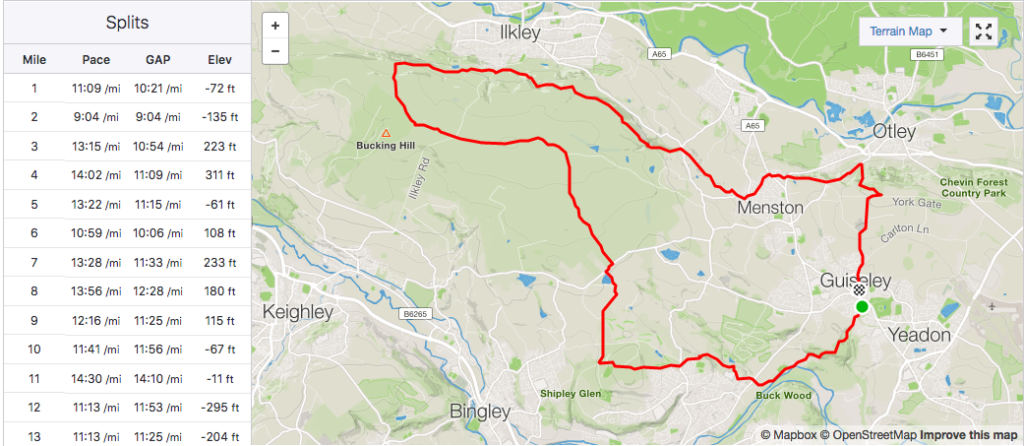

FRB collated some stats which showed I overtook people all the way round. These were my placings.

PyG 752/767

HB 734/761

Ri 731/758

Wh 717/740

HI 708/740

Ing 695/701

Finish 686/701

His words: “Not saying you were a tortoise, but by’eck, it pays to pace.”

Thanks here: to FRB, of course. To all the volunteers and marshals and race committee. I’ve had some insight into what it takes to put on a race with nearly 1,000 runners. It’s a lot of hard work done for little reward. Thank you. Thank you, also, to everyone who cheered, hugged, handed out sweets or kindness. All of it was profoundly welcome.

I ran Rombald’s Stride on inadequate training. I ran the Yorkshireman on inadequate training. I don’t recommend that as a race strategy. But I am extremely proud of myself: finishing so far back of course dents my pride, but that’s a stupid way to think. I did well. I did very, very well.

I wonder what I could do if I followed a training plan?

x

x